The Prime Minister has reportedly said he fears that a second wave of coronavirus infections could hit the UK within weeks.

It comes as Spain, France, Germany and other countries see upsurges in new cases.

How big is the current spike on the continent? And should Britain be bracing itself for a second wave?

Covid-19 in the UK

How do we measure the prevalence of coronavirus in the UK? There isn’t one perfect statistic.

The first place to look is the number of people testing positive. Some 581 people tested positive after a swab (or “antigen”) test across the UK on Tuesday.

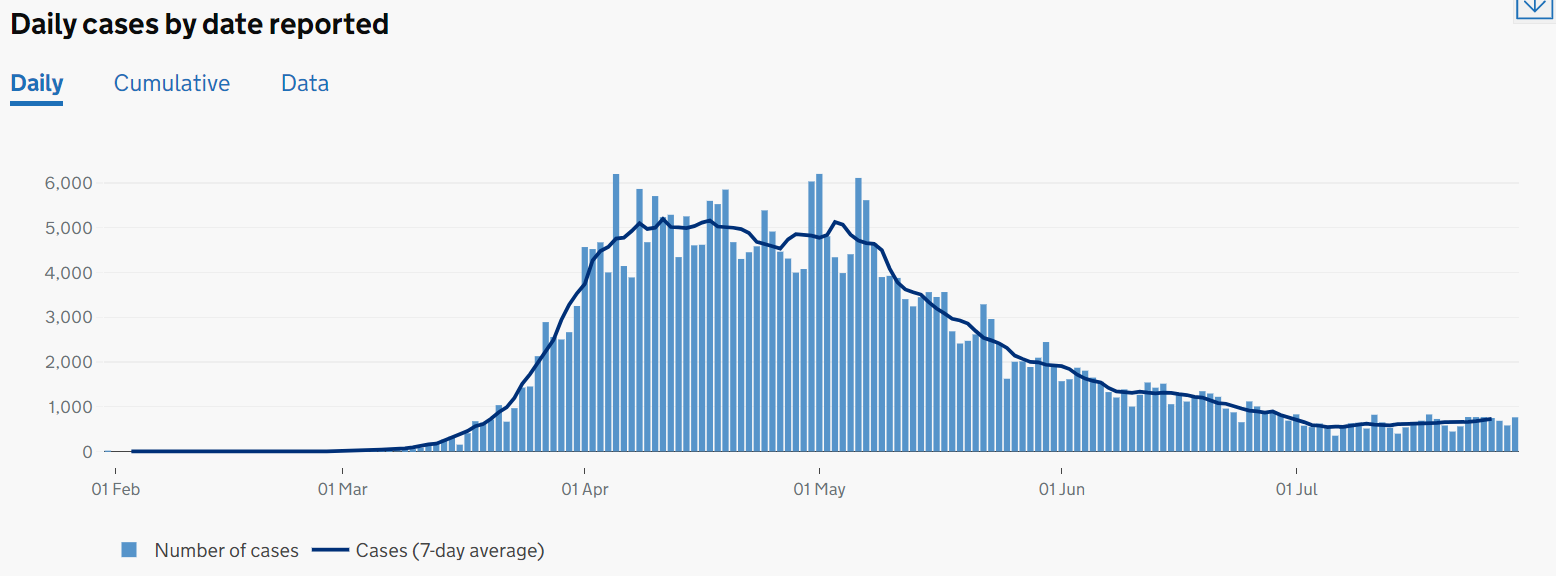

We can see the long-term trend in government figures for new cases in England: the number of new confirmed cases has fallen dramatically since April, but it has never fallen to zero.

In fact, the rolling average number of people testing positive has risen slightly from around 550 a day to around 700 in the last three weeks:

Of course, data from tests is not likely to be completely accurate. No testing regime will pick up every case, and as the UK’s ability to carry out tests has risen sharply, we would expect this to lead to more positive tests.

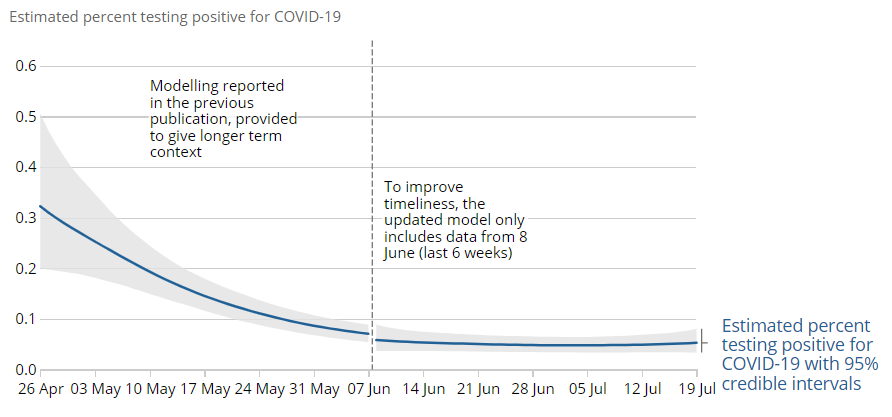

But the trend in confirmed cases mirrors the trend we see in another measure of coronavirus prevalence: the ONS’s survey of cases in the community (outside hospitals).

It’s a similar story here: there was a sharp decline in coronavirus rates, but the decrease appears to have levelled off in recent weeks:

What is the current rate of infection?

None of this should come as a surprise, according to experts. We have eased lockdown measures in recent weeks, so this would be expected to lead to a rise in new infections.

That may not be a disaster, as long as the rate of transmission remains low.

This is where the “R” number comes in. The number represents the average number of people who become infected by someone carrying the virus. If it falls below 1, the illness can be expected to slowly die out. The higher the number, the greater the chance of the virus spreading exponentially.

Working out the current “R” number is a matter of modelling and estimates, rather than hard facts.

Today scientists at Cambridge’s MRC Biostatics Unit estimated that there are really about 3,000 new infections in England each day, and that the “R” rate “is close to 1 in most regions of England”.

The government puts the reproduction number across the whole of the UK in the range of 0.7 to 0.9.

Rise in Europe

Other European countries have seen sharper rises in new cases, according to data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Using a seven-day average, we can see that there have been substantial upticks in Germany and France in recent weeks, and a very large increase in Spain, where cases almost trebled in July:

This gives some insight into why the British government has decided to reintroduce quarantine restrictions on people returning from Spain, although representatives of the Spanish government have questioned the fairness of the measure, since the outbreaks in Spain have been very regional.

We can see how much local surges are to blame for Spain’s coronavirus resurgence in ECDPC figures here: it’s true that many regions outside the north-east of the country have fewer cases per 100,000 people than some regions of the United Kingdom.

Will there be a second wave?

Few experts are willing to make a firm prediction.

Many scientists point out that Britain has never managed to stamp out the virus altogether, so talk of a new distinct “wave” might be misleading. There have been hundreds of cases a day for months, and we would always expect a rise as distancing measures are eased.

What about the threat of new transmission from the continent?

Dr Michael Head, Senior Research Fellow in Global Health, University of Southampton, said: “It is a little early to say definitively whether some European countries, such as Spain or Germany, are experiencing the start of a second wave, or simply seeing spikes in their caseloads.

“The long-term decline to zero cases of COVID-19 will always see bumps in their graphs within the downward trend.”

Will a sustained resurgence of the disease on the continent mean it inevitably spreads to Britain? Again, we can’t say for sure, although we know that infected cases arriving from abroad played an important role at the beginning of the outbreak.

Researchers at Imperial College found last month that many infection cases arrived in the UK from Italy and Spain in early March, leading to “heavier seeding than we’d expected”.

It’s not surprising that the conversation has moved on to what measures the British government should introduce to reduce the numbers of infected cases from overseas.

The government has said there is currently no alternative to a 14-day quarantine period for travellers returning from coronavirus hotspot, despite complaints from leading figures in the travel industry.

But scientists from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine published a preprint article this week which found that a quarantine of just eight days, with a test on day seven, was almost as effective at detecting infections arrivals as isolating people for 14 days.