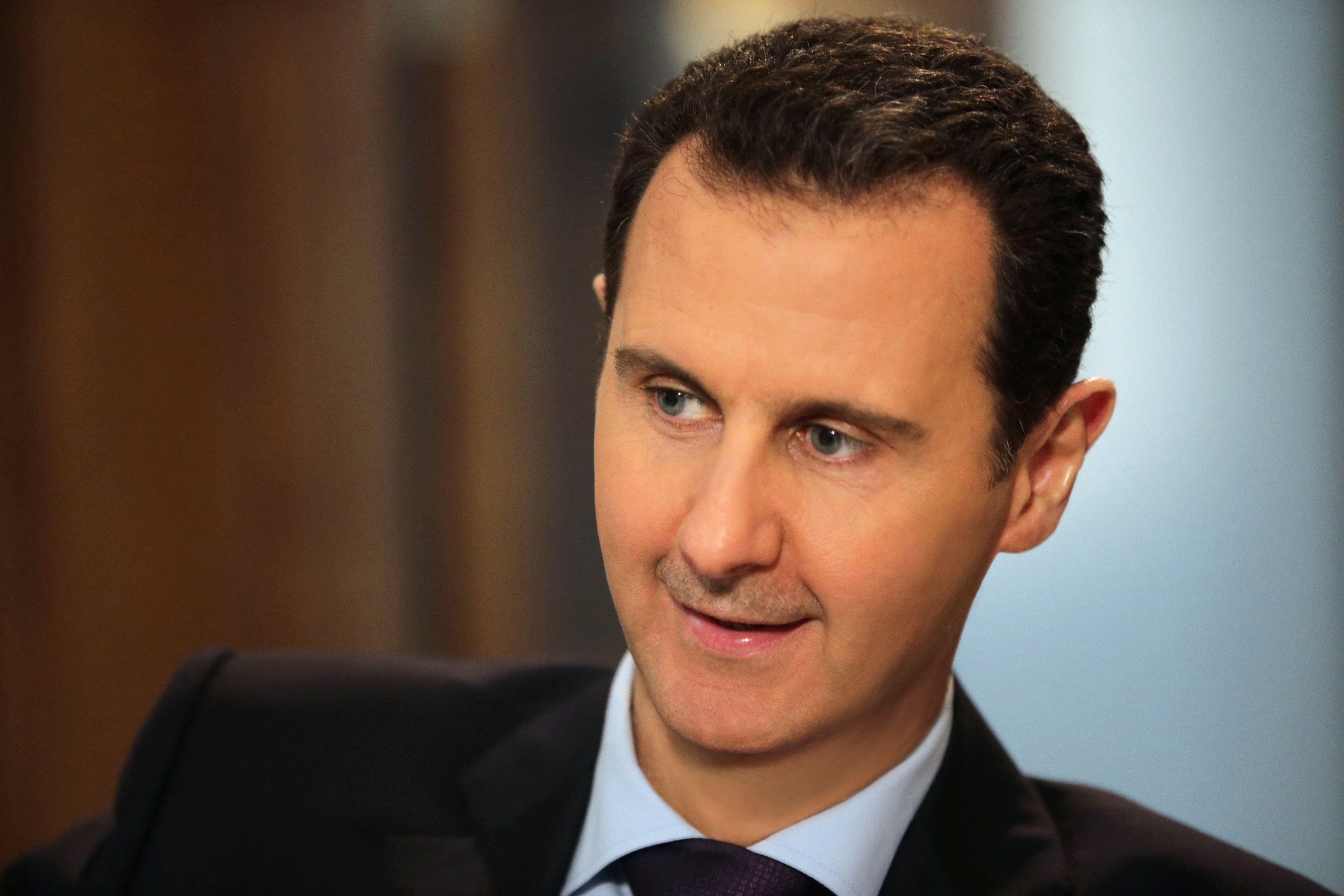

President Bashar al-Assad gave a rare interview in English today, as world leaders continued to criticise a suspected chemical attack on a rebel-held area of Syria.

Theresa May said the British government believes it is “highly likely” that an air strike on the village of Khan Sheikhun in Idlib Province on April 3 was the work of the Assad regime.

Donald Trump has already made it clear he holds the Syrian government responsible for the attack, which was widely reported to have killed more than 70 people including young children.

The US president ordered a Tomahawk missile strike on the regime’s Shayrat airbase in response.

President Assad made a number of questionable claims during the exclusive AFP interview, during which he repeatedly denied Syria’s responsibility for the deaths in Khan Sheikhun.

“You have a lot of fake videos now… We don’t know whether those dead children were killed in Khan Sheikhun. Were they dead at all?”

President Assad appears to be casting doubt on whether an attack on Khan Sheikhun happened at all.

He said in the interview: “Definitely, 100 percent for us, it’s fabrication.

“Our impression is that the West, mainly the United States, is hand-in-glove with the terrorists. They fabricated the whole story in order to have a pretext for the attack.”

Oddly, this contradicts previous statements on Khan Sheikhun made by Assad’s allies in Moscow and by members of his own government.

Representatives of Russia and Syria have previously stated that an airstrike on the village did take place last week.

And although many of the details were disputed, they did not dispute the presence of chemical weapons at the scene.

A day after the attack, Major General Igor Konashenkov, a spokesman for the Russian Defense Ministry, gave a statement saying Syrian planes had hit a rebel chemical weapons stockpile.

The following day, Assad’s foreign minister Walid Muallem also referred to an “airstrike by the Syrian army on an ammunition depot of al-Nusra terrorists with chemical weapons inside it”.

There is a disagreement about the timing. Russian and Syrian government sources put the attack at after 11am local time, whereas local eyewitnesses said it happened hours earlier.

But initially, neither Syria nor Russia denied that people were at risk of exposure to chemical weapons.

The story was that this was an airstrike with conventional weapons, and chemicals at the scene belonged to rebel groups.

Strangely, President Assad appears to be casting doubt now on whether there was a deadly attack of any kind.

Were the children “dead at all”?

A number of videos were posted apparently showing victims from the area suffering the after-effects of chemical poisoning.

Some of the videos are gathered, along with translations, on this page on the citizen journalist site Bellingcat. A warning: some of the footage is distressing.

Doctors at the scene highlight similar symptoms among the patients: they are unresponsive, their pupils are constricted, and they do not react when torches are shone in their eyes.

People sympathetic to the regime tend to doubt evidence gathered from rescuers and medics in rebel-held areas.

But a Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) medical team said that they saw similar symptoms in patients brought to a hospital near the Turkish border from Khan Sheikhoun.

We haven’t seen any compelling evidence that any of the video footage from Khan Sheikhun has been faked, but as it happens, we don’t need to rely exclusively on video evidence anyway.

Reporters at Channel 4 News spoke to individuals in the area who suffered the after-effects of poisoning and saw the same symptoms in other people. People told us that they had lost family members, identifying themselves and their relatives.

The Guardian newspaper sent a reporter called Kareem Shaheen to Khan Sheikhun two days after the attack.

He filed an article that included interviews with witnesses, including a man identified as Abdulhamid al-Yousef (pictured below) who lost his wife and twin baby daughters in the attack.

The Telegraph actually carried a photograph of the same man cradling the bodies of the baby girls shortly before he buried them in a mass grave.

Shaheen also filed photographs of freshly-dug graves in the village, said to contain the bodies of 20 victims.

Local doctors gave detailed accounts to journalists of treating victims, describing symptoms which experts said were consistent with nerve agent poisoning.

Save the Children told FactCheck that trusted local partners had given them specific details of three children under six who were taken from Khan Sheikhun to a local hospital suffering from symptoms consistent with neurotoxin poisoning.

It is not clear whether these children survived, but there were first-hand reports from medical staff working on the ground that other infants with similar symptoms had certainly died, the charity said.

Other international organisations with partners on the ground in Syria, including the World Health Organization, have similarly put their concern on record.

The WHO said the likelihood that this was a chemical attack was born out by lack of external injuries, respiratory distress and “additional signs consistent with exposure to organophosphorus chemicals, a category of chemicals that includes nerve agents”.

Several academic experts have gone on record as saying that the likely culprit in this case is sarin – the nerve gas invented by the Nazis – and that the Syrian regime is more likely than any rebel group to have the capacity to launch a sarin attack.

Chemical weapons experts also say it is implausible that conventional bombs falling on a stash of sarin would have spread the deadly gas without destroying it.

“The only information the world has had until this moment is published by al-Qaeda.”

It’s true that the attack site is in territory controlled by Islamist militants, some linked to the al-Qaeda terror group. But it’s not true that the only evidence of a chemical attack comes from local rebels.

As we have seen, independent journalists have been able to analyse images of the attack, using geo-location and other tools to verify that it did in fact happen.

And international humanitarian organisations have relayed information from trusted local partners who work in the area where the attacks took place.

The British delegation to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) said UK scientists have tested samples from Khan Sheikhun and the samples “tested positive for the nerve agent sarin, or a sarin-like substance”.

Turkish officials said they conducted post-mortems on victims and also found evidence of sarin.

“We gave up our arsenal a few years ago. Even if we have them, we wouldn’t use them.”

Syria was certainly supposed to have given up its chemical weapons stockpile in 2013, but there is widespread suspicion that the regime held on to some poisons.

An investigation by the OPCW and the UN found that Syrian forces dropped chemical weapons on rebel forces in 2014 and 2015, after the regime agreed to destroy its stocks. In both attacks, the chemical used was thought to be chlorine.

The same report also accused the so-called Islamic State of launching an attack with mustard gas.

Human Rights Watch accused regime forces of dropping chlorine on residential areas of Aleppo at least eight times in November and December last year.