The government says it wants most hospital doctors on seven-day contracts by the end of this parliament, claiming thousands of patients are dying unnecessarily thanks to lack of weekend cover.

The British Medical Association says its members welcome a seven-day NHS, but it wants to know how ministers propose to pay for the extra hours.

The Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, says he is ready to force junior doctors and consultants to accept new working conditions if an agreement cannot be reached in the next six weeks.

Are you really more likely to die if you are hospitalised at the weekend? And are there other times to avoid?

Is there a “weekend effect”?

Yes – and we’ve known about it for years.

This Imperial College London study looked at emergency admissions in England in 2005/06. It found that the odds of you dying in hospital were 10 per cent higher if you were admitted at the weekend.

Out of 50 conditions with the highest number of deaths, 17 were associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality among weekend patients.

The authors noted that the trend could result in “a possible excess of more 3369 deaths” – more than the number of people killed in road accidents in Britain that year.

This raised a red flag, but some questions remained unanswered. It seems that people are less likely to go to accident and emergency at weekends, so maybe you get a different mixture of cases than in the week.

A more recent study by the same team looked at planned operations rather than emergency cases, and tracked how likely patients were to die within 30 days of having the procedure.

The odds of dying within a month of the operation odds of death were 82 per cent higher if it was done at the weekend, compared with Monday.

One obvious inference is that you get a less experienced doctor at the weekend, so the quality of care will be lower, although no research of this kind can prove conclusively that this is the reason for the higher risk.

What about Friday?

For the first time, this study highlighted a “weekday” effect as well as a weekend one. Your chance of dying was lowest if you had surgery on a Monday and grew steadily throughout the week:

Having an operation on a Friday was associated with a 44 per cent higher chance of dying than Monday.

It’s not absolutely clear why, although the authors suggested that serious complications are more likely to occur within 48 hours of surgery.

So if you go under the knife on Thursday or Friday, you may be more likely to need emergency care at the weekend, when there are fewer or less experienced doctors around.

Right. It’s Saturday. I’m in hospital. Should I panic?

No – or not yet. This study, which we think is the source of Mr Hunt’s claim about a 15 per cent increased risk at weekends, suggests that you are actually less likely to die on the day if you go into hospital on a Saturday or a Sunday.

This is about outcomes – what is likely to happen in the 30 days after you are treated in hospital.

Is this just an NHS problem?

No. Several reviews of studies from different countries have found the same trend.

This Japanese paper looked at 72 studies from all over the world, covering 55 million patients. Weekend admission was associated with a 15-17 per cent increased risk of mortality.

The authors said: “There are at least two potential explanations for our results. First, these differences reflect poorer quality of care in hospital at the weekend and second, patients admitted on at weekend could be more severely ill than those admitted on at weekday.

“We believe that poorer care at the weekends is the much more likely explanation.”

So is the lack of doctors to blame?

It’s impossible for research of this kind to prove definitively that lack of experienced doctors at weekends is the main factor, but that is what the authors of several of these studies believe is most likely.

There’s no real dispute about the benefits of improving weekend cover in hospitals.

The government, NHS England, the BMA, healthcare think-tanks like the Nuffield Trust and the King’s Fund all back the move to a proper seven-day service.

The political argument is about whether the government is going to fund improved weekend services properly.

Are there any other times to avoid?

Possibly. This in-depth study on two hospital campuses in Berlin found that the risk of patients dying changed according to the time of day, week and year.

February was the highest-risk month for surgery, with a 16 per cent increased risk of death, and surgery carried out in the afternoon was 21 per cent more likely to kill you than at other times of day.

We’re not aware of any studies that show whether there are similar changes in risk in NHS hospitals, although it seems that some dates can be more dangerous than others.

NHS patients were traditionally warned to avoid hospital on the first Wednesday in August, when newly qualified hospital doctors took up their posts.

In 2009 an Imperial College London study found that this was no myth: death rates were 6 per cent higher on “Black Wednesday”, when patients were likely to find themselves in the hands of less experienced doctors.

Anecdotally, the festive period is also a good time to stay off the wards, with more experienced doctors likely to be on leave, although this is hard to pin down with statistics.

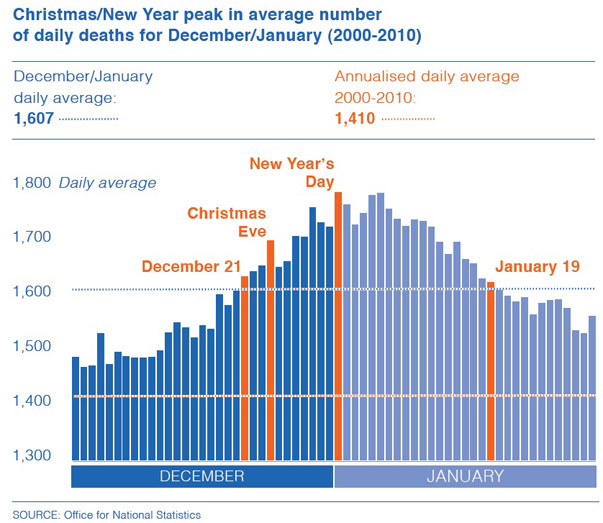

ONS figures from 2000 to 2010 show there is an increased risk of death between 21 December and 19 January , with a peak around new year’s day (graphic: NHS Choices)

But this measures deaths in the population, not just deaths in hospital or following an operation, so all kinds of other factors – weather, alcohol, more traffic – could come into play.

What hospitals should I avoid?

That’s hard to say. We do have Summary Hospital-level Mortality Indicators – which compare the number of people who die after hospitalisation compared to the number you would expect to die based on the national average.

The latest figures show that nine out of 137 trusts have higher than expected mortality.

But these SHMI scores are controversial. Some doctors think the public should ignore them, while others say they provide a good indicator of how hospitals are performing.

The official guidance states that the data “cannot be interpreted as the number of avoidable deaths at the trust as it is not a direct measure of quality of care” and that a higher than expected score “should not immediately be interpreted as indicating bad performance”.

And the data is only made public at the trust level – you can’t tell whether your nearest hospital is experiencing more deaths than average.