The claim

“If we vote to leave, then the £350m we send to Brussels every week can be spent on our priorities like the NHS.”

Kate Hoey, 9 October 2015

The background

The battle over Brexit began in earnest today with the launch of a cross-party campaign for Britain to leave the EU

Vote Leave is being bankrolled by millionaires who have previously donated to the Conservatives, Ukip and Labour.

Eurosceptic MPs supporting the campaign include former Conservative environment secretary Owen Paterson (an old friend of this blog) and Labour MP Kate Hoey.

Ms Hoey says Britain is sending £350m a week to Brussels, which could be spent on other priorities.

Is this a Brexact number? Or is Hoey talking hooey?

The analysis

By the time the in/out referendum takes place before the end of 2017, you may well be sick of hearing about £350m a week, because it is a claim repeated endlessly in Vote Leave’s campaign material and is sure to surface again and again.

The figure simply comes from taking Britain’s gross annual contribution to the EU’s finances and dividing it by 52.

That gross figure was £18.3bn in 2014/15, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which works out at just under £352m a week.

But just looking at the gross contribution doesn’t tell the whole story, because we get about half of the money back.

About half of this £9bn or so is returned via the rebate negotiated by Margaret Thatcher in 1984, and the rest comes in the form of payments to Britain from various EU pots like the European Agriculture Fund for Rural Development.

This is how the House of Commons Library tracked spending to 2014. The orange bars are the annual gross payments. The black line is the net amount once you take away the various clawbacks:

And this is what the OBR thinks Britain will pay into the EU from 2014 to 2021, gross and net.

The net contribution in 2014/15 was £9.1bn – just under half the gross figure of £18.3bn.

We put it to Vote Leave that they were misleading voters by talking about the gross figure. After all, if I lend you £50 and you give me £25 back, I’ve given you £25, haven’t I?

A spokesman told us the issue is one of control. Once we have handed over the £18.3bn, it’s up to the EU how it hands a lot of it back.

“The money is divided by Brussels, not by people here. We probably wouldn’t spend it on the same things they would.”

If the figures above are right, this argument works for about half the money Britain gets back from Europe – that’s “public sector receipts” – the light green bit of the first graph.

And there is a whole other massive argument we need to have.

While there is no dispute that membership of the EU costs taxpayers significant amount of money, supporters of the union would say that Britain reaps the rewards in increased trade, employment and so on.

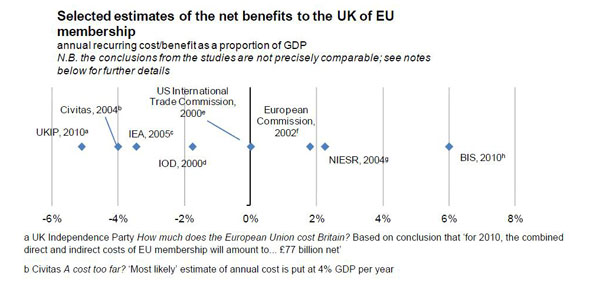

But this is hotly contested. Various economists have tried to do cost/benefit analyses of membership, only to produce wildly different estimates, possibly not unrelated to the views of the people doing the analysis:

We’ve covered this in detail before (here and here). Suffice to say that some organisations have produced calculations claiming that Brexit would save Britain tens of billions, while others have said the economy might shrink on a scale comparable to that of the global economic crisis.

It all depends on the assumptions you put in to your model. Ukip economists evidently think EU regulations impose a straightforward cost on UK businesses.

Others have disputed this, saying the regulations bring economic benefits that (just about) outweigh the costs.

There are few easy answers here, and the British government has never commissioned an independent analysis of overall net effect on the economy of EU membership.

Vote Leave told us they do not intend to produce an assessment of this kind themselves either, but are convinced that leaving the EU would be in Britain’s economic interests.

The verdict

It’s true that we give the equivalent of £350m to Brussels every week… but then we get about half of it back.

That still means we are handing over about £9bn a year on aggregate – more than double the amount paid in 2008 in real terms.

Some would argue that what we pay each year is outweighed by the benefits to the economy that come from EU membership.

But this is hotly contested – and it may be impossible to settle the economic argument before the referendum.