David Cameron has been accused of dodging questions on his record as prime minister.

Labour – and some media commentators – are suggesting Mr Cameron failed to answer properly questions on food banks and zero-hours contracts during last night’s interview with Jeremy Paxman.

The prime minister did concede that the use of food banks had gone up, but said he didn’t have the exact figures.

He was more precise about zero-hours contracts, saying they accounted for about one in 50 jobs, and saying some people choose to work on that basis.

Let’s see if we can fill in some of the blanks.

Food banks

Mr Cameron used to like to point out that the use of food banks – which provide emergeny parcels of food to people in danger of going hungry – started to go up under Labour.

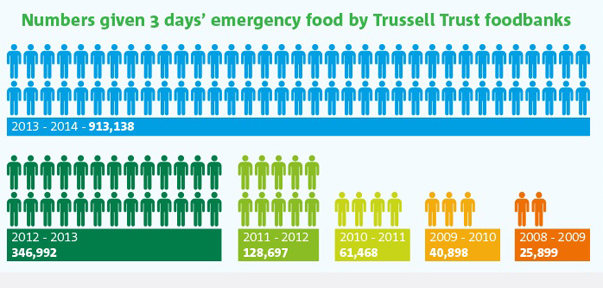

That’s perfectly true, but the rise we saw before 2010 has been dwarfed by the speed of growth under the coalition:

The Trussell Trust – the main provider of food banks in the UK – said they had given three days’ food to more than 900,000 people in 2013/14, up from 347,000 the year before.

The numbers are on course to top 1 million in 2014/15.

Mr Cameron told Paxman: “Obviously there has been an increase in food bank use. That’s partly because of, you know, the difficulties we have faced as a country.

“It’s also, Jeremy, because we changed the rules. The previous government didn’t allow jobcentres to advertise the existence of food banks.”

It’s true that the Conservatives changed policy to let benefits advisers direct people facing hardship to local food banks – but this hasn’t been a significant factor in the rise in food bank use, according to the Trussell Trust.

The charity told us only about 2-5 per cent of people who come to them are referred by benefits advisers.

But people who use the banks often blame the benefits system for their predicament. About 45 per cent of people say “benefit delays” or “benefit changes” are why they have turned to food banks.

Zero-hours contracts

On the face of it, this looks like bad news for Mr Cameron too.

At first glance, the Office for National Statistics figures suggest a massive recent rise in the number of people on “zero-hours” contracts – where someone is not contracted to work for a specific number of hours, and is only paid for the hours they work.

The ONS recorded 697,000 people on zero-hours contracts in 2014 compared to 168,000 in 2010. The latest figure is 2.3 per cent of people in employment, so just over the one in 50 claimed by Mr Cameron.

But we should be careful not to assume there has really been a big jump under the coalition.

These figures come from the Labour Force Survey – a questionnaire of about 40,000 households used to estimate changes in the wider job market.

The statisticians think this massive recent rise in people who say they are on zero-hours contracts could just reflect the fact that the term has been used more widely in the media over the last couple of years, so more people are likely to know what it means.

The ONS says: “It is not possible to say how much of this increase is due to greater recognition of the term ‘zero-hours contracts’ rather than new contracts.”

This is not the only estimate available.

In 2013 the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) estimated that just over 1 million people, or 3.1 per cent of the work force, were employed on a zero-hours basis – about four times the official estimate.

Not all of them were complaining.

CIPD surveys found that 47 per cent were satisfied with having no minimum hours, 27 per cent say they are dissatisfied and 23 per cent were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

Some 60 per cent of zero-hours workers said they were “satisfied with their current job” – compared to 59 per cent of all employees.

Quality and quantity of work

The prevalence of zero-hours contracts is often used to suggest that, despite the rise in employment seen under the coalition, the quality and security of jobs has fallen.

It’s true to say that there are more self-employed people and more people doing part-time and temporary jobs than just before the last election – but there is also more employment and more permanent and full-time jobs too.

The actual jobs mix has actually changed very little, as our two pie charts show:

http://static.data.c4news.com/Lzsvg/index.html

These figures don’t include every type of employment counted by the ONS – and the headline employment figures don’t usually include temporary work. We have selected them to show changes in temporary, part-time and self-employed work.

The proportions have hardly changed. In February to April 2010 60 per cent of workers were employees working full-time. In the latest quarterly figures the number was 59.8 per cent.

http://static.data.c4news.com/Y5Glh/index.html

The change in employment represents a rise of more than 2 million people in employment of one kind or another under the coalition – more than 1.1 million of these were full-time employees.

So the rise in employment claimed by the coalition can’t be explained away by increases in self-employment, part-time and temporary work.