The Deputy Prime Minister and the Ukip leader are set to go head to head in their second televised debate tonight.

Nigel Farage is expected to come under some pressure to explain recent remarks in which he expressed his admiration for the Russian president, Vladimir Putin.

But the debate is likely to return to the key questions on Britain’s continued membership of the EU and immigration.

We’ve FactChecked the Lib Dem and Ukip positions on the big issues and we can make an educated guess about the arguments each man is going to bring to the table this evening.

Here’s where we are on some of the big questions.

Leaving the EU would put 3 million jobs at risk

Leaving the EU would put 3 million jobs at risk

A Clegg favourite. The claim is based on research first done in 2000, which suggested that about 2.5 million people owed their jobs directly to exports of goods and services to EU trading partners and 900,000 more jobs had been created indirectly by EU trade.

But the author, Professor Iain Begg of the London School of Economics, has specifically told FactCheck his analysis does not suggest that all those jobs would be lost overnight if Britain pulled out of the EU.

Britain would no doubt continue to trade with Europe. The real question is how easy it would be to negotiate dozens of separate free trade agreements with the various member states and others. That’s an unknown quantity.

Another piece of research, also published in 2000, by the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR), came up with a similar estimate of jobs associated with exports to the EU countries.

Again, the think tank specifically said that didn’t mean we would lose all those jobs if we pulled out of the EU.

Mr Clegg used to say that 3 million jobs “relied directly” on our participation in the single market. Perhaps the Lib Dem reader read our original FactCheck back in 2011, because he now tends to use a more cautious form of words, saying the jobs are “linked” to EU membership.

EU membership costs £55m a day

EU membership costs £55m a day

This figure is being heavily touted by Ukip at the moment, but the party hasn’t explained to us how it gets this number.

It’s perfectly true to say that Britain pays in more to Europe than it gets back in rebates, to the tune of billions of pounds a year.

The OBR estimates that the net cost of membership will be a little over £10bn in 2014/15.

That’s not the end of the story. EU supporters say the economic benefits of membership more than make up for this outlay, while eurosceptics say the real costs are much higher.

None of this is simple. For example, Ukip’s argument that the EU adds a huge administrative burden to British businesses rests on the assumption that all EU regulations are a straightforward drag on business efficiency.

But the regulations are supposed to bring net economic benefits by improving consumer protection and freeing up markets.

No one has ever done a definitive, uncontroversial cost-benefit analysis of EU membership, and we doubt whether it could ever be done.

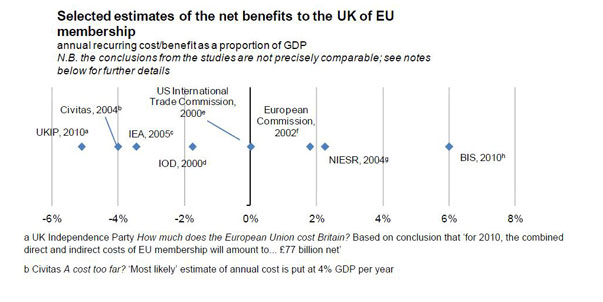

Our BFFs at the House of Commons Library have done an independent review of various analyses that have been attempted. They lay out their findings in a handy diagram:

Our take-home message would be: beware of anyone who states glibly that Britain loses or gains astronomical amounts of money from EU membership.

The true costs and benefits are fiendishly difficult to work out. The most credible independent analyses out there suggest that any overall economic cost or benefit is likely to be pretty small.

For the same reason, we would treat pro-EU claims that membership gives every British household £3,000 with a pinch of salt too.

This is simply the other side of the coin, with the supposed benefits exaggerated and the costs played down.

An enormous proportion of British law is made in Brussels

An enormous proportion of British law is made in Brussels

Estimates of the amount of domestic law in various countries that originates from the EU range from 84 per cent to just 6.3 per cent.

These numbers come from research done in Germany and Sweden respectively and it’s not clear to us that either of them can simply be transposed to Britain.

Ukip say it’s 75 per cent, while others quote a 2005 UK government estimate of 9 per cent, but the methodology used to work these numbers out is flimsy.

The big question is whether you count every EU regulation as a national law. Should a regulation on the shape of bananas be given equal weight to, say, the creation of a new criminal offence?

The House of Commons library concludes: “All measurements have their problems and it is possible to justify any measure between 15 per cent and 50 per cent or thereabouts.”

Of course it’s impossible to say how many laws Britain would have implemented anyway if it had stayed out of the EU.

There really has been a lot of immigration

There really has been a lot of immigration

No one disputes the scale of migration to this country in recent decades, and in particular around the time of the opening up of the labour markets to the new eastern European EU member states in 2004.

Mr Farage is probably right to say that the influx is the biggest in British history.

..but immigration is probably good for the economy

..but immigration is probably good for the economy

That is the conclusion of several pieces of research that attempted to count up how much migrants pay in to the economy through tax and national insurance contributions, compared to what they take out in terms of benefits and services.

In 2009 academics at University College London found that migrants from the A8 countries of central and eastern Europe who joined the EU in 2004 were 60 per cent less likely than native-born Brits to claim benefits, and 58 per cent less likely to live in council housing.

In every year since 2004 the A8 immigrants had paid in more than they had taken out. They were younger, better educated and less likely to claim state benefits.

Another UCL study last year found that Between 1995 and 2011 EEA immigrants paid in 4 per cent more to the system than they took out, whereas native-born Britons only paid in 93 per cent of what they received.

Between 2001 and 2011 recent EEA immigrants contributed 34 per cent more than they took out, a net contribution of £22bn.

Despite endless claims to the contrary, the UCL research does include in-work benefits in its calculations.

All this chimes with other research from the OECD and the Office for Budget Responsibility.

A snapshot study by the Department of Work and Pensions found that 16.4 per cent of working-age UK nationals were claiming a working-age benefit last year compared to 6.7 per cent of non-UK nationals.