“If you really believe that what people are seeing is rising incomes in this country, I don’t think that’s what people in this country are feeling.”

Ed Miliband, 14 August 2013

The background

Ed Miliband called it “the biggest issue facing the country – the cost of living crisis”.

On the campaign trail in Walworth, south London, the Labour leader said that despite signs of an upturn in the economy, voters were complaining that rising inflation and stagnating wages are leaving them squeezed.

Not everyone was pleased to see Mr Miliband. At one point, he was forced to scramble for cover when an irate member of the public pelted him with eggs, apparently in protest at “favouritism to the banks”.

But with falling unemployment and inflation down, and growth and house prices up, Labour is having to put most of its eggs in the cost of living basket when it comes to attacking the government’s economic record.

Mr Miliband said: “So many people are finding themselves out of pocket, with prices rises faster than wages, and they just conclude that this government is out of touch.”

It’s a message Labour has been trying to hammer home since they put out this pamphlet earlier this month.

But the chancellor, George Osborne, appears to cast doubt on the existence of a cost of living crisis. Writing in the Times last month, he said: “Disposable incomes grew by 1.4 per cent above inflation last year despite the squeeze, the fastest for three years.”

The analysis

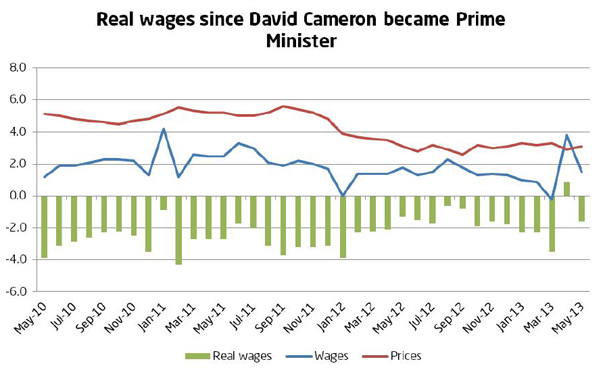

There’s no dispute that inflation is rising faster than wages. In fact, prices went up faster than wages in almost every month since David Cameron became prime minister, as Labour were quick to point out.

House of Commons Library research for Labour suggests real wages have fallen in every region of the UK since 2010 and we are doing worse than every other country in the G7 group of leading economies.

But whether this amounts to a big black mark for the prime minister and chancellor is debatable.

Firstly, as economists Paul Gregg and Stephen Machin have pointed out, real wages started to slow down and stagnated from about 2003 after decades of growth.

So sluggish wage growth appears to be a long-term pattern that has little to do with the recession or the current government.

Secondly, falling wages may be the reason why unemployment has been less of a problem following the most recent downturn than it was after the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s.

“However painful falling wages may be, it is important to note that they may have been instrumental in preventing a much larger increase in unemployment,” is how the professors put it.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has also made this point, saying: “To the extent that it is better for individuals to stay in work, albeit with lower wages, than to become unemployed, the long-term consequences of this recession in terms of labour market performance may be less severe than following the high unemployment recessions of the 1980s and 1990s.”

Labour has repeatedly cited the IFS’s research on falling wages without quoting them on this important point.

The institute’s researchers also point out that average real hourly wages have fallen more for workers at the top end of the income distribution at the bottom, meaning earnings inequality has stagnated or fallen slightly.

Clearly this doesn’t chime with Labour’s line that the coalition is “standing up for the wrong people”, and Mr Miliband has had to confine his attacks on that front to pointing out that bonus payments were unusually high this April, presumably because employers delayed payouts to take advantage of the new 45p tax rate.

What about Mr Osborne’s controversial comment to the effect that households saw their incomes grow faster than inflation last year?

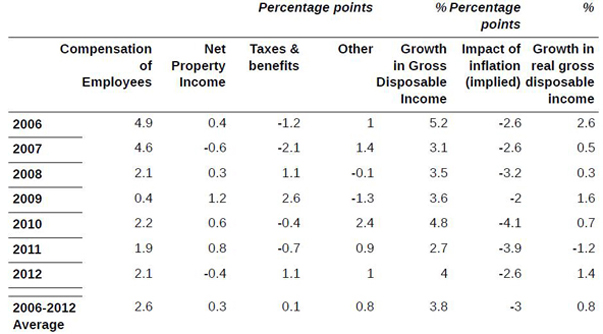

This is perfectly true, and reflects the fact that there is a difference between wages and income. While Labour have concentrated on falling wages, the chancellor picked up on a different measure – real gross disposable income.

This encompasses wages and other sources of income like benefits, interest earned on savings and dividends on shares to give a broader picture of total household income.

The chancellor was right to say that this measure was up 1.4 per cent over the whole of 2012, after adjusting for price inflation. This was a big improvement on 2011 and 2010.

Critics pointed out that the chancellor neglected to mention the most recent quarterly figures, which show a massive 1.7 per cent point drop in real disposable income in the first quarter of 2013.

That came alongside a big drop in household saving ratios, suggesting people are raiding the piggy bank to offset falling income.

All of which suggests that we could indeed be looking at a serious squeeze on living standards.

But this is only data from one quarter. It could turn out to be a blip, and the numbers could be revised in the future.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with the chancellor electing to look at annual figures instead to point out a longer-term positive trend in disposable income.

The verdict

Mr Miliband is right to say that wages have generally stagnated since 2010 while inflation has stayed above the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target.

But experts point out that wage stagnation a) began under Labour and b) could be the reason why unemployment isn’t as bad as it could be.

George Osborne got some stick last month for failing to point out that the most recent data we have on disposable income is pretty worrying.

But he was correct to say that overall disposable income, as opposed to just wages, actually rose faster than inflation last year.

But never mind the facts, perhaps it really is how people feel that is most important to the politicians.

As Mr Miliband knows, 81 per cent of respondents in a recent YouGov poll said they believed prices grew faster than household incomes over the last year.

By Patrick Worrall