A shameless imitation of Tony Blair. A bid to steal the centre ground. His most outspoken attack on Jeremy Corbyn yet.

That’s what various pundits have said about David Cameron’s Tory conference speech.

The Prime Minister also made a number of factual claims which caused FactCheck readers to raise their eyebrows. Let’s take a look…

“The north – more Tory.”

He was talking about the north of England here, the morning after the general election.

We were surprised at this, but it’s true. While everyone talked about Ukip taking votes from Labour in the north, the Conservatives quietly staged a bit of a comeback.

This study from the University of Sheffield’s Political Economy Research Institute has all the figures.

Across the North West, North East and Yorkshire and Humberside regions, the Tories increased their haul of parliamentary seats by a modest one compared to 2010. But the party increased its share of the vote substantially across the north.

The researchers conclude that the Conservatives must “be taken seriously as an electoral force in this part of England” and Labour “cannot afford to take its traditional strength in Northern England for granted”.

“Thousands of words have been written about the new Labour leader. But you only really need to know one thing: he thinks the death of Osama bin Laden was a tragedy.”

The full interview (with Iranian-funded broadcaster Press TV) in which Jeremy Corbyn made his remarks about bin Laden are all over the internet.

The Labour leader repeats his opposition to the death penalty and criticises American foreign policy before turning to the death of the al-Qaeda leader at the hands of US special forces.

He says: “There was no attempt whatsoever that I can see to arrest him, to put him on trial, to go through that process.

“This was an assassination attempt, and is yet another tragedy upon a tragedy upon a tragedy.

“The World Trade Center was a tragedy, the attack on Afghanistan was a tragedy, the war in Iraq was a tragedy. Tens of thousands of people have died.”

“More than 150 people a day are moving in thanks to our Help to Buy scheme.”

This works if we look at the numbers of people who have bought properties using the main Help To Buy equity loan scheme in the last month we know about: June 2015.

In that month – the most successful on record – there were 4,745 completed sales, which works out at 158 a day.

But if you look at the main Help to Buy scheme over its whole lifetime, people have bought 56,402 properties over 27 months, which averages out at a less impressive 69 or so a day.

“We made a start in the last five years with our Troubled Families programme. It’s already turned around the lives of over 100,000 families.”

We noted last year that dodgy statistics had dogged the government’s aim to improve the lives of “troubled families” said to be disproportionately likely to get involved in crime, addiction and other social problems.

Mr Cameron said back in 2011 that there were 120,000 families who needed intensive help from the authorities. The government then changed the definition of what a “troubled family” was – but still said there were 120,000 of them.

Experts thought it would cost £14,000 to £25,000 per family to make an impact. In the end, the government only gave local councils £4,000 per household, telling them to make up the shortfall.

By the end of the last parliament, the government said it had “turned around” the lives of just under 117,000 families (just missing the target). That means truancy, antisocial behaviour and youth crime rates have fallen or an adult has found continuous employment.

We don’t know how many families would have seen this kind of improvement if they had not been enrolled on the scheme.

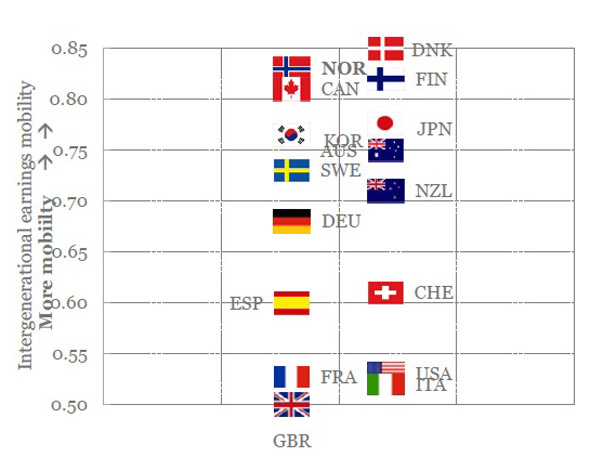

“Britain has the lowest social mobility in the developed world.”

True, if we take “the developed world” to mean the advanced economies of the OECD organisation, and if we choose one common measure of social mobility – intergenerational earnings elasticity:

The OECD figures for 2015 (above) suggest that you are less likely to earn more than your father did than in any of the other countries in the group.

There was no change in the UK’s international rankings compared to 2007 figures, so it’s fair to say that things didn’t get worse under the coalition – but only because they couldn’t get any worse.