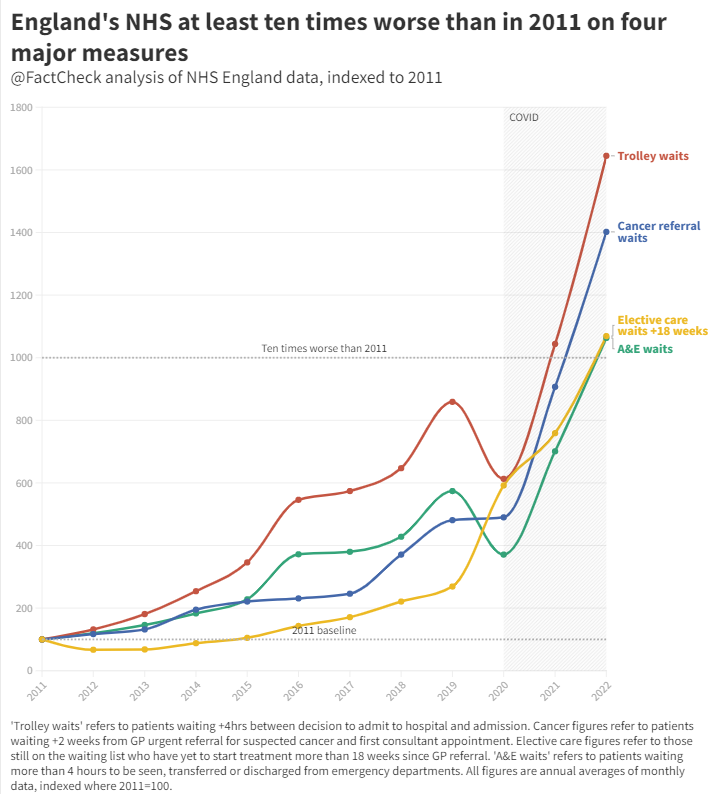

England’s NHS is at least ten times worse than it was in 2011 on four major measures, FactCheck analysis can reveal.

These metrics – patients waiting more than four hours in A&E, those waiting more than four hours on a trolley to be admitted to hospital, people seen by a cancer consultant more than a fortnight after a GP referral, and those still on the elective care waiting list after 18 weeks – are some of the main ways that experts track the overall state of England’s healthcare system.

They’re also some of the key targets that the NHS sets itself.

This exclusive analysis of NHS England data by Channel 4 News FactCheck uses a baseline of 2011 to show how, by each of these measures, the health service is performing over ten times worse today.

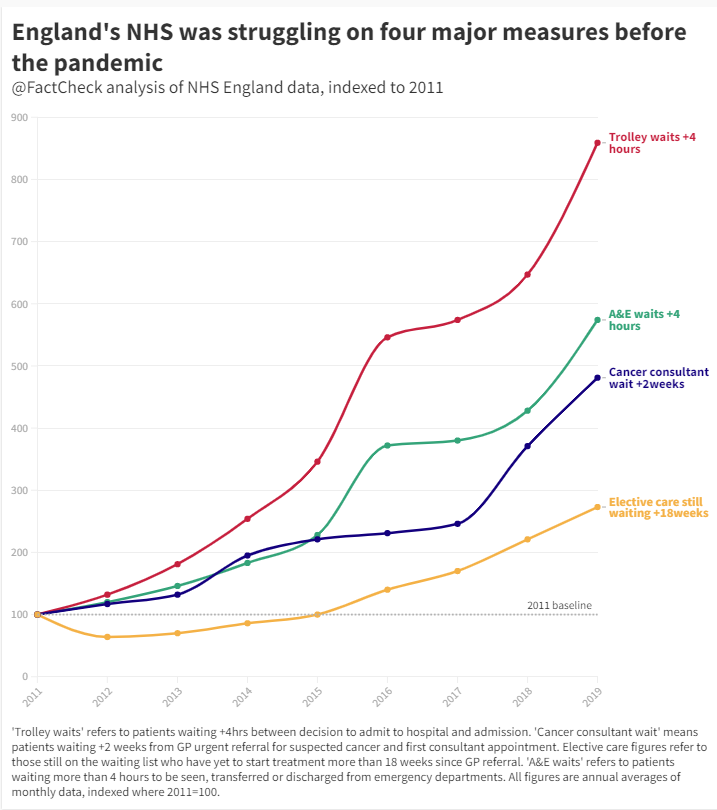

The crisis began before the pandemic

Unsurprisingly, the last three years have been a particularly acute period for the NHS, but our analysis shows performance worsening on each of these four measures even before Covid hit.

By 2019, the number of people waiting more than four hours on a trolley for a proper hospital bed was eight times higher than it had been in 2011.

Even the number of people waiting longer than 18 weeks on the elective care waiting list, which fared less badly than our other measures, rose nearly threefold between 2011 and 2019.

As the independent Nuffield Trust think tank pointed out to FactCheck, “the 4-hour A&E target has not been met since July 2015, and the 18-week [elective care target] has not been met for over 5 years. The target for 85% of people to start cancer treatment in less than 2 months was only met once in the last 8 years.”

All of these figures include periods before the pandemic.

Covid, austerity and the perfect storm

The early months of 2020 saw an apparent improvement in emergency medicine, with long trolley waits and A&E delays falling.

But much of this was caused by people stayed away in the first Covid lockdown, believing they were helping the health service. (At the time, health authorities began actively campaigning to remind people that the NHS would still treat non-Covid symptoms and that it was not against lockdown regulations to see a doctor.)

Yet this well-intentioned move from the public would eventually exacerbate future problems as underlying illnesses went untreated, only to flare up later in more urgent, severe forms.

The Nuffield Trust explained to FactCheck that “during the first wave of Covid-19, there was a considerable fall in urgent referrals and cancer treatment being commenced”. This, along with the temporary pause in some cancer screening services, meant that by the time patients reached the NHS, they were more unwell and needed more care.

Yo-yoing demand partly explains the explosion in long waiting times across the NHS in 2021 and since. But it’s not the only factor.

Take the 7 million people currently waiting for elective care in England – that’s life-changing treatments like hip and knee replacement, or cataracts surgery. The Nuffield Trust says this eye-watering figure “cannot be solely attributed to Covid-19 but instead is a predictable consequence of the collision between a pandemic and a health system already stretched beyond its limits”.

To understand this fully, we have to go back to the early 2010s, when the Conservative-led coalition began their policy of austerity.

Almost every part of the public sector saw its budget cut. On paper, the NHS was spared, with spending rising in every year of the decade, even as other areas felt the pinch.

But what those spending rises didn’t account for was the UK’s ageing population. When we do that – and add inflation to the mix – we can see that between 2010 and 2015, health spending per head of population actually fell by 0.07 per cent a year, according to Nuffield Trust calculations.

In the latter part of the decade, the real-terms cuts were less severe (0.03 per cent a year). But still, at a time when many experts thought the NHS needed more money, it was getting less.

Since the pandemic, the Conservative government has injected more cash into the system, with current plans showing a real-terms rise of 2.05 per cent a year. This is on a par with the Thatcher and Major administrations of the 1980s and 90s – but still less than half as generous as the last Labour government, when real-terms population-adjusted spending rose 5.67 per cent a year on average.

Health and Social Care Secretary Steve Barclay said: “Across the UK, Europe and internationally, health systems are seeing a significant impact on operational performance due to the impact of the pandemic, the rapid spike in flu, Strep A and the ongoing high levels of Covid.

“That’s why, as I set out this week, we’re taking urgent action to ease pressures on A&E, including investing an additional £200 million to get medically fit patients out of hospital quicker and boost the social care workforce, on top of our £500m discharge fund, creating the equivalent of 7,000 more beds through innovations like virtual wards, and putting £50 million towards expanding capacity in emergency departments through new discharge lounges and ambulance hubs.

“This is on top of record funding, including up to £14.1 billion for health and social care over the next two years – the highest spend on health and care in any government’s history.”

After this article was published, NHS England told FactCheck: “Waits in A&E, ambulance handover delays – and therefore delays getting ambulances back out on the road – are as a direct result of high bed occupancy and a lack of capacity in hospitals.”

This article was updated on 18 January to clarify that there was no blanket national pause in cancer screening services during the early part of the pandemic.