The claim

“Today’s report shows that Europe brings each UK household £3,000 a year.”

Gareth Thomas, 4 November 2013

The background

The question of whether Britain gains or loses economically from membership of the EU is a difficult one to answer.

No UK government has commissioned a cost/benefit analysis, and economists who have taken on the massive task have inevitably disagreed.

But from today’s headlines you might be forgiven for thinking that we had finally solved the puzzle.

The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) says it has “looked beyond the political rhetoric” in weighing up the pros and cons, and concluded that staying in the EU is “overwhelmingly” in Britain’s economic interestes.

The business lobby group suggests that EU membership is worth between £62bn and £78bn a year, around 4-5 per cent of the country’s total economic output, or about £3,000 per household.

This was picked up by Labour, among others, with the shadow Europe minister Gareth Thomas saying: “Today’s report shows that Europe brings each UK household £3,000 a year.”

That figure has featured prominently in news reports today. Should we take it seriously?

The analysis

The first thing to note is that there is no new research being published today. The CBI has simply carried out a review of existing literature on the subject.

Specifically, the business lobby group has looked at five research papers, listed in this table.

This is by no means an exhaustive survey of the work done on this topic, and it is heavily biased towards studies which support the pro-Europe position.

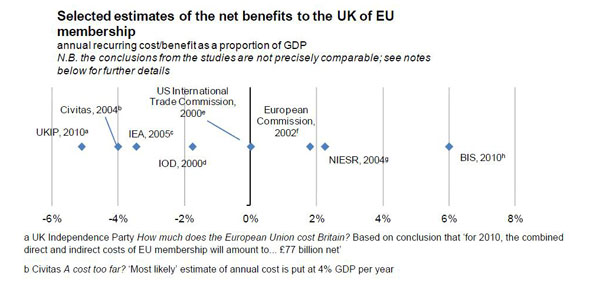

Notable omissions include cost/benefit analyses by the Institute of Directors (IOD) and the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR).

The IOD concluded that after totting up all the economic costs and benefits, staying in the EU leaves Britain out of pocket, to the tune of 1.75 per cent of GDP.

A report by NIESR in 2004 suggested the opposite: staying in the EU creates a small net gain, and the UK’s output would be just over 2 per cent lower a year if we left.

Note that the difference between these estimates is not vast. Further studies by the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) and the US International Trade Commission found it essentially too close to call either way.

The author of the IEA paper, the late Professor Brian Hindley, put it like this: “Any economic gain or loss is small – almost certainly less than 1 per cent of GDP… more precise or more sophisticated calculations will not arrive at a large number for either gain or loss.”

This is all a long way from the CBI’s estimate of EU membership boosting GDP by 4-5 per cent a year. Have these studies been missed off the list because they are “off-message”, as far as the CBI is concerned?

Most other literature reviews we’ve seen mention these papers. Here’s an alternative review of the literature by the independent House of Commons library, with the IOD and NIESR studies included. Note that the choice of literature is completely different from the CBI, and represents a much broader spectrum of opinion.

Four out of eight studies quoted here think EU membership creates a net cost to the economy. Two are cautiously optimistic, the aforementioned American study sits right on the fence, and only the department of Business, Innovation and Skills view is strikingly positive about Europe.

What about the studies that the CBI does cite? Two are EU-wide studies that find a positive effect but make no estimate of an effect on UK GDP specifically.

That 5 per cent figure quoted for the study at the top of the list isn’t an annual benefit, like the others – it is the effect on today’s European GDP of the common market: 5 per cent above what it otherwise would have been.

Two of the studies claim a net gain for Britain of just over 2 per cent of GDP a year. One is negative, predicting GDP would fall by 2.5 per cent if Britain left Europe.

But the conclusion the CBI draws from all this is that there is a clear annual benefit of 4-5 per cent of national income.

Where does this optimism come from? It’s not really clear. The only rationale is that “the studies are not mutually exclusive”, which presumably means that rather than, say, taking an average of the estimates on offer, you can simply take the good bits from each one and heap them on top of one another.

The end result is that the CBI’s forecast is twice as optimistic than any of the studies it claims to be based on.

The verdict

So should we take this claim that EU membership boosts GDP by up to 5 per cent seriously? We think not. It’s way more optimistic than most other estimates, and we can’t don’t really know how the CBI researchers have arrived at this figure.

It doesn’t appear to be a fair reflection of the evidence they themselves have looked at – and the choice of evidence seems partial and one-sided to begin with.

Does that mean we can unequivocally prove that it is NOT in Britain’s interests to stay in the UK?

Certainly not – and we doubt whether the most detailed cost/benefit analysis in the world could settle the question either way.

Why not? Well, as the CBI report itself says, so many costs and benefits are real but intangible, impossible to boil down to numbers and dependent on counterfactual arguments: what would have happened if history had been different?

A europhile could argue that the European project has created peace and security, as well as a harmonised single market. These things undoubtedly have economic benefits, but how do you quantify them?

Unfortunately, most people won’t read the sensible small print in this study. What they will take away is the headline claim that EU membership is worth £3,000 to each British household.

As far as we can see, this very precise number is not based on any real evidence.

By Patrick Worrall