The background

The UK and Scottish governments have published rival estimates of how Scotland’s finances would fare in the event of a “yes” vote in September’s independence referendum.

And the estimates are wildly different. The Treasury says Scots will benefit to the tune of about £1,400 a year if they choose to stay in the United Kingdom.

The Scottish Nationalist government says almost exactly the opposite, predicting an annual independence “bonus” of £1,000 for every man, woman and child in Scotland.

Who’s right?

The analysis

Clearly, there’s a massive difference of opinion here. But there are some things all sides agree on.

Public spending in Scotland is consistently higher than the UK average – about 10 per cent per head. In 2012/13 public spending per head was £12,265 in Scotland and £10,998 across the UK.

But tax revenue from oil and gas in Scottish waters wipes out that shortfall.

If we give Scotland a “geographical share” of oil revenue – working on the most likely assumption that hydrocarbons in the Scottish part of the North Sea would become Scottish assets after independence – Scotland has paid in a bit more than it takes out in recent years.

Today’s Treasury paper glosses over this fact by saying:

“Including a geographic share of oil revenues, Scotland’s overall fiscal position has on average been broadly the same as the UK’s since devolution.”

“Including a geographic share of oil revenues, Scotland’s overall fiscal position has on average been broadly the same as the UK’s since devolution.”

That may be “broadly” true but it doesn’t tell the whole story. In four out of the last five years, if you include oil, Scotland has paid in more to the Treasury than it has taken out as a percentage.

So when Scotland’s first minister, Alex Salmond, says:

“People in Scotland are getting a raw deal under the current arrangement – paying more into Westminster than we get out.”

“People in Scotland are getting a raw deal under the current arrangement – paying more into Westminster than we get out.”

…he’s got a point.

Has this always been the case? Have the Scots essentially been robbed by Westminster over the decades? Probably not.

Professor Brian Ashcroft from Strathclyde University has looked at tax receipts paid in by Scotland and spending taken out since 1980 and reckons spending has been slightly higher (his graph):

Oil revenues might mean Scotland has paid in more than it has taken out of the UK bank account over the last five years, but they aren’t enough to put Scotland in the black. A newly independent country would still spend more than it earned: it would start with a net fiscal deficit.

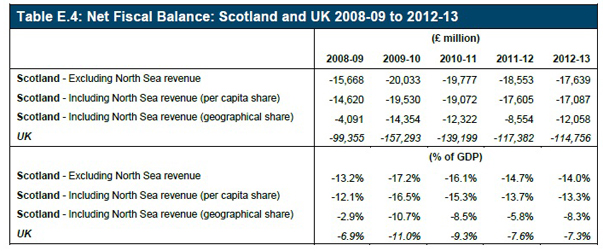

But that Scottish deficit might well be smaller than the UK deficit. That’s what has happened in four out of the last five years (compare the bottom two rows):

Will Scotland be in a stronger position than the UK in 2016/17? That’s the claim made by the Scottish government today. They think the new country would be running a net fiscal deficit of 2.8 per cent of GDP, slightly smaller than the forecast for the whole of the UK.

That’s if Scotland takes on a share of the UK’s national debt based on population size – perhaps the most likely scenario.

Here’s where the big dispute starts. This is a much more optimistic forecast than independent bodies have come up with. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) thinks the deficit will be more than 5 per cent of GDP.

The difference is almost entirely explained by the fact that the Scottish governments uses more optimistic projections of future oil earnings than almost anyone else.

Here’s how the Treasury illustrates this in a graphic from its new paper. The dotted lines are Scottish government forecasts, the solid ones from the Office for Budget Responsibility, which has had to consistenly write down its estimates of future oil revenue.

The IFS says: “Our figures and the Treasury’s figures are based on the Office for Budget Responsibility’s projections. The Scottish Government report instead uses their own – higher – forecasts for North Sea revenues.

“Their figures assume that Scotland will receive £6.9 billion (or 4.1 per cent of Scottish GDP) in tax revenues from offshore oil and gas production in 2016–17, rather than the £2.9 billion (1.7 per cent of GDP) forecast by the OBR.”

Which forecast will prove to be more accurate? We don’t know, but it’s fair to say that the Scottish government’s figures are based on optimistic forecasts rejected by independent economists.

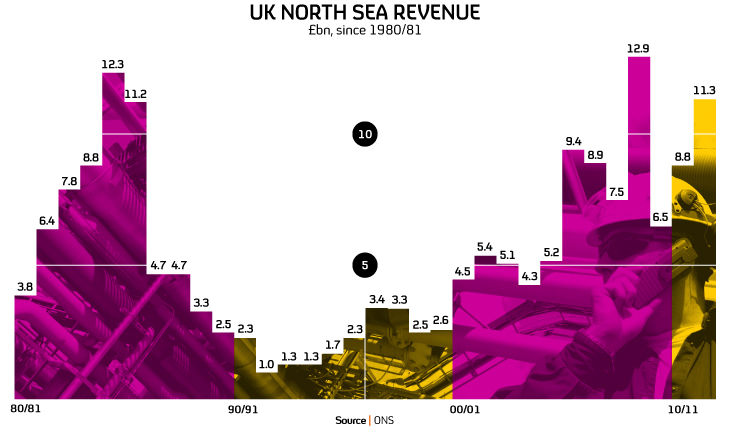

And we can certainly say that since oil prices and production level can fluctuate wildly, and hydrocarbons will make up a larger share of the Scottish economy, the result will be more volatility.

Here’s our overview of UK North Sea revenue since 1980, which has as many peaks and valleys as the Cairngorms.

The Scottish government has said it wants to invest money in a Norway-style oil fund to help smooth out the spikes.

That’s a nice idea. FactCheck has often thought it would be nice to stash money in an investment fund for a rainy day. The trouble is, there’s never enough money at the end of the month. Will it be different for Scotland?

This goes to the heart of other big claims in the Holyrood document – that independence will boost the economy to the tune of an extra £1,000 for every Scot.

All the nationalists are really saying here is that if Scotland’s productivity, working-age population and employment rate grow, its economy will grow.

As a Scottish government press release headline puts it: “Improved economic performance key to boosting tax revenues.”

Well yes – it’s impossible to argue with that. But why will independence automatically improve the Scottish economy? There’s no real explanation of that.

The IFS sums it up like this: “Whilst it may turn out to be the case that the Scottish economy does a great deal better after independence than it would as part of the UK, planning on this as a central assumption seems less than cautious.”

The think-tank also points out that the Scottish government is assuming that public service spending does not grow faster than productivity – which goes against the historical evidence.

The Treasury paper similarly depends on assumptions about the future that may or may not come true. Basically, it says the money from oil and gas will be swallowed up by costs: the one-off costs of setting up new government institutions, the ongoing drain on resources from an ageing population, and the alleged cost of various fiscal policies the Scottish government has promised to implement.

Again, the principle of “garbage in, garbage out” holds sway. If any of the projections the UK government is making about population change, oil revenues and so on turn out to be wrong, the £1,400 “UK dividend” will be wrong too.

One hole has apparently already appeared in the Treasury analysis, with LSE professor Patrick Dunleavy accusing the department of misrepresenting his research on the one-off costs of new government institutions.

Mr Salmond has tried to extract the maximum capital from this, saying:

“This leaves the Treasury claims about Scotland’s finances without a shred of credibility.”

“This leaves the Treasury claims about Scotland’s finances without a shred of credibility.”

No. The UK government paper mentions the Dunleavy research, but does not rely on it. It puts the cost of setting up a new independent state at £1.5bn, at the high end of an estimate produced by Canadian academic Robert Young.

Even if that number proved to be much too high, it wouldn’t put much of a dent in the £1,400. Professor Dunleavy’s comments are embarrassing for the Treasury, but they don’t undermine the whole analysis.

The Scottish government told FactCheck it disputes the Treasury’s costing of £1.6bn for its promised fiscal policies, saying the various measures (tax cuts and extra childcare provision) are designed to increase long-term economic output. But Holyrood did not offer an alternative figure for the overall costs and benefits of the policies.

The verdict

We’ve said it till we’re blue in the face: there are just too many unknown quantities to make a definitive prediction of the economic health of an independent Scotland.

If oil prices soar, Scotland could be sitting pretty. Even if they don’t, Scots won’t face abject poverty: “onshore” tax revenues, taking oil and gas out of the equation, are only slightly lower in Scotland.

But spending is higher, and the challenges of an ageing population, the uncertainty over currency and a probable long-term decline in oil receipts are all real concerns.

And let’s not forget that the distribution of national assets and debts will all be up for negotiation in the event of a “yes” vote.

This is why so many independent economists are significantly more pessimistic than the Scottish government’s rose-tinted view of things.