Labour put out a dossier last week claiming that “the Tories are costing the average household” about £6,000 a year – while a Labour government would cut household costs by £6,716.

The shadow business secretary, Rebecca Long-Bailey, has denied the party’s figures are misleading.

But Labour’s calculations are based on a string of very dubious assumptions. In fact, FactCheck thinks that almost every figure they have used is questionable.

Rising bills?

Labour say: “The Conservatives’ failure to curb rising bills has cost families almost £6,000 a year since 2010.”

They say energy, water, broadband, rail fares, childcare, prescription charges and rent have all gone up since 2010, when the Conservatives went into coalition with the Lib Dems.

Most of these bills are charged by private providers, so it’s debatable how much of the price rises you can blame on the government.

Still, Labour want to bring energy, water, rail and broadband into public ownership – so they are encouraging voters to make a comparison between the current system and a programme of nationalisation, which they say will bring savings to consumers.

But have bills really risen while the Conservatives were in government?

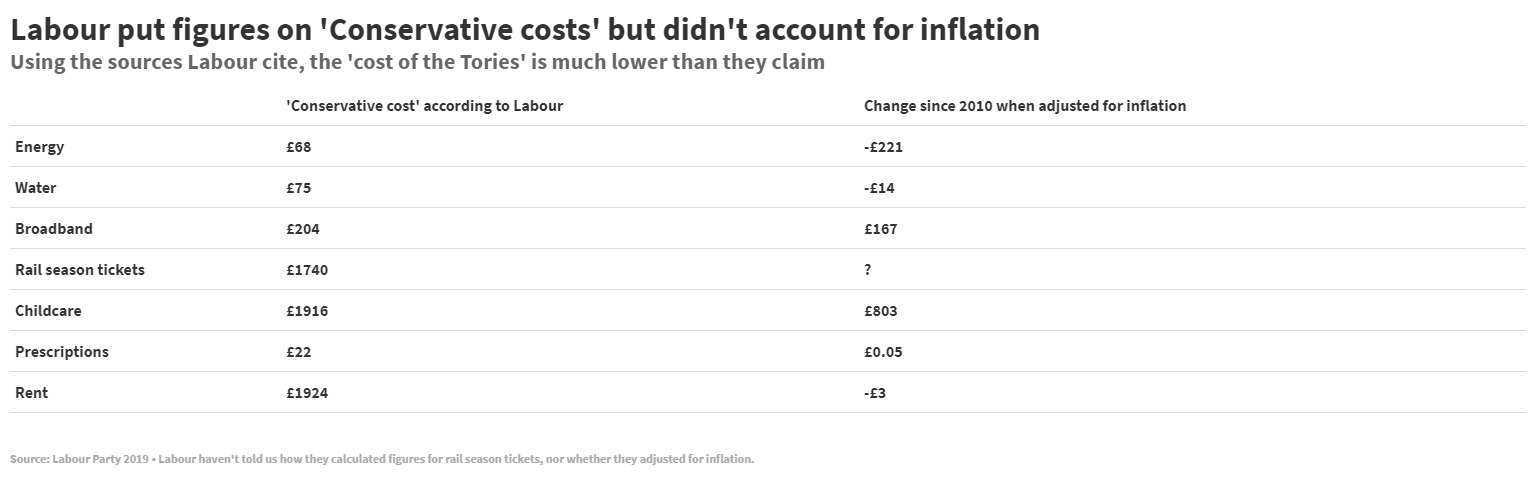

In many cases, Labour have simply compared cash figures from 2010 and the most recent data, without allowing for inflation.

If we take the same numbers Labour cite in the document and put them in “real terms”, the supposed price rises are actually smaller – or disappear altogether.

We’ve used the Bank of England’s inflation calculator to do this. Other measures of inflation are available, so it may be possible to quibble with our numbers here.

But the principle is the important thing: much of the purported rise in the cost of living since 2010 claimed by Labour can simply be accounted for by inflation.

Labour themselves frequently criticise government policy for making “real-terms” cuts – sending out press releases that rely on figures which are adjusted for inflation.

Energy

Labour say the average dual-fuel bill (gas and electricity) has risen by £68, comparing the 2010 and 2018 figures in this Ofgem report.

But when we adjust for inflation, bills have actually fallen in real terms over that time – by some £221 on average.

Water

It’s a similar story with water. Labour claim a rise of £75, based on a 2010 water bill of £340.

We think they have used the number from the wrong year. The real figure in the Ofwat document they link to is £343.

In 2018 prices, that’s £432, and Labour say current bills are £415 on average – using a different source.

Assuming these figures are comparable, water bills have fallen slightly in real terms compared to where they were when the Conservatives took office, on Labour’s evidence.

Rail fares

The claim here is that rail season tickets have risen by £1,740 per household since 2010 (that’s based on two season tickets per home). It’s based on internal Labour analysis, which the party have not shared with us.

Industry sources have told FactCheck that Labour’s figure is wrong, and that the real true average annual season ticket price (including all routes and first and standard class tickets) is £2,648.

We don’t have a comparable price for 2010 so we can’t get an accurate figure for how much rail prices have actually changed in real terms.

Childcare

Labour’s claim partly rests on the rising cost of care for the average child aged two. Allowing for inflation, this has gone up by £803 since 2010 – less than half what Labour claim.

And the government pays for 570 hours of free childcare a year for children aged three and four, so our “average family” must have a child aged two for Labour’s claim to add up.

Prescription costs

Labour say the costs of a single prescription has risen by £1.80 since 2010. But the difference in price is almost exactly accounted for by inflation: the cost is about the same in real terms.

Rent

Labour say median weekly private rents have risen from £156 in 2010 to £193 in 2019. The figures relate to England and come from this government report (annex table AT1.12).

It looks like Labour have mistakenly taken the mean average figure from these stats, not the median as they claim. Either way, average private weekly rents have also risen very slightly below the rate of inflation, contrary to the rise Labour claim.

Note that Labour’s promise is to give renters the right to a home “where rent rises by no more than inflation”. On this evidence, they are promising to deliver something that already happened under the Conservatives.

Broadband

Labour claim a £204 rise in annual broadband bills of since 2010. As with water, they have used two different data sources.

And again, they haven’t adjusted for inflation. If we do that, the real terms rise is £167 since 2010.

We’re not sure it’s really possible to produce a sensible figure for the rising cost of broadband, since the service people were paying for in 2010 is so different to 2019 in terms of download speed and bandwidth, with the number of likely devices used per household increasing.

Labour also say they won’t finish rolling out free broadband until 2030 anyway, so it’s hard to see how any possible future saving could be attributed to the next government (or even the one after that).

What’s the grand total?

We can’t tot all these figures up, because we don’t have a reliable source for the cost of rail season tickets, and we don’t think it’s fair to include broadband.

Across the other things Labour have included – energy, water, childcare, prescriptions, broadband and rent – we calculate a real-terms rise of around £729 since 2010, less than a fifth of the £4,209 claimed by Labour:

This is just a back-of-envelope calculation, and all that £729 can be accounted for by above-inflation rises in childcare costs. But of course, these costs are heavily dependent on the assumptions you make about how many children a family has and how old they are.

If we remove childcare from the equation, the real-terms cost of the goods and services Labour cite are actually lower now than they were in 2010.

Average family?

The document Labour have published purports to show how the finances of the “the average household” or “average families” have changed.

But the fictional family Labour are using to illustrate their points is not really average.

For all these rises in cost and future benefits to apply – including Labour’s policy on extending free school meals – the family would have to consist of two adults who commute to work using rail season tickets, with one child aged two and another at primary school.

Labour’s whole claim that the Conservatives have cost people almost £6,000 rests on taking an alleged large increase in the price of rail season tickets, then doubling it.

But there can’t be many households with two season ticket commuters. We don’t know exactly how many people buy season tickets, but YouGov figures suggest less than 5 per cent of Brits take more than 50 train journeys a year.

The childcare claim rests on having a child aged two, and the figure for prescription costs is based on someone paying for one prescription every month. Latest stats show 84 per cent of NHS prescriptions are already free of charge.

Labour’s “better offer”?

The other side of Labour’s equation is the claim that their policies will save the average family £6,716. There are a lot of problems with this figure too.

Labour puts these savings down to a drive to make homes more energy efficient, and plans to nationalise energy, water, broadband and rail.

Research from the Public Services International Research Unit at the University of Greenwich appears to be the source for Labour’s claim that nationalisation will save the average household more than £100 on their annual water and energy bills.

But the paper actually says: “Savings are quantified on a per household basis to indicate the value gained by each household, whether it is used to reduce prices or improve services through investment.”

In other words, a future government might save money by nationalising utility companies, but the research doesn’t assume that this will be used to bring down bills.

The money might have to be ploughed back into investment, and indeed Labour have often said that the privatised utility companies have under-invested in recent years.

There is also a more overarching question too: will Labour be able to deliver on all these policies, given the unfunded spending commitments they have made in this general election campaign?

As FactCheck has noted before, the funding document that accompanied Labour’s manifesto does not say how Labour will pay for the £58bn needed to compensate WASPI women.

And the initial costs of implementing Labour’s nationalisation plans are unknown. This week the Institute for Fiscal Studies said the cost of paying shareholders to take companies into the public sector “would certainly come, at the very least, to many tens of billions of pounds”.

‘Not misleading at all’

In an interview with BBC Radio 4’s Today programme last week, Labour’s shadow business secretary, Rebecca Long-Bailey defended Labour’s dossier, saying: “It’s not misleading at all. As a political party we need to best encapsulate what we’re offering in a way that people understand. And I think that makes sense to people, that they ultimately could be up to £6,700 better off.

“And then it’s up to the families themselves to identify which policies apply to them and which ones they like and which ones they don’t like. But I think to provide that easy figure to identify what it is we’re trying to achieve is a sensible thing to do.”

A Labour source insisted the cost of living calculations applied to “a typical family”, adding: “This isn’t a ‘one size fits all’ example, but an indication of the thousands of pounds people across the country will save with Labour.”

On adjusting for inflation, the source said: “Inflation is simply a measure of the cost of goods and services.

“What we’ve done is measure the Government’s failure to tackle a number of rising costs that have a direct impact on household accounts.

“It wouldn’t make sense to then correct that for inflation. Also, no one looks back at a rise in their rent, or increase in their energy bills and thinks: ‘What would that be in real terms?’.

“Taking that into account would be forgiving the Government for its failure to act to keep costs down, and its failure on wage growth.”