“We have seen over a quarter of a trillion pounds in infrastructure spending since 2010.” Theresa May, 15 November 2017

Theresa May’s first proper question at this week’s Prime Minister’s Questions was about whether the government would spend more on Britain’s infrastructure.

You might have taken her answer, then, to refer to government spending.

But the Treasury told us they get to this figure of a quarter of a trillion pounds by adding together public and private sector investment in Britain’s infrastructure. They haven’t published the full methodology.

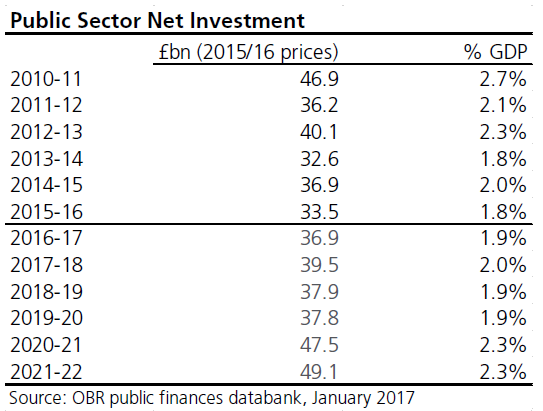

What about public money alone? These figures from the House of Commons Library show what has happened to Public Sector Net Investment on infrastructure since 2010:

As we can see, government investment as a share of national wealth was cut year-on-year several times under the Conservatives, but it is predicted to rise to 2.3 per cent by 2020.

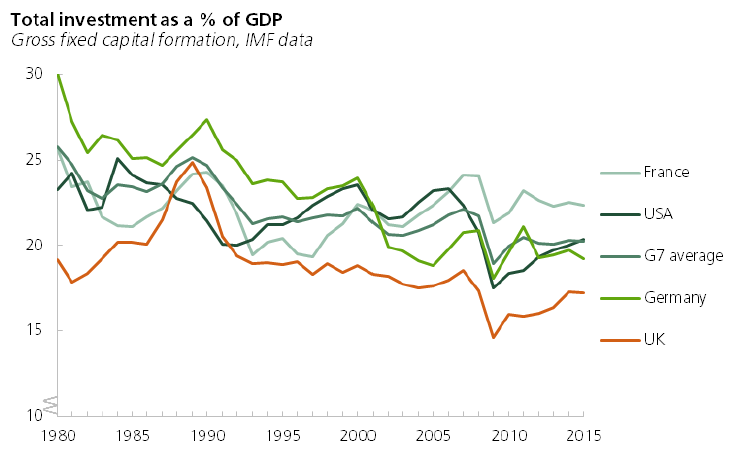

Is this a lot? The Commons Library also compares Britain’s infrastructure spending with other major advanced economies. (These international figures include private investment, like the Treasury, but they may not be calculated in the same way.)

We can see that Britain lags behind other wealthy countries and spends less than the G7 average on infrastructure:

“We have protected police budgets.” Theresa May, Prime Minister’s Questions, 15 Nov 2017

The current government has promised to “protect” – that is, to not cut – police budgets in the current parliament, but this claim is arguable.

The money police forces get from central government has in fact been cut, and they have had to increase the share they get from local council taxes to make up the shortfall.

After doing this, the total amount forces have to spend has remained “broadly flat in cash terms”, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies.

This means revenues have continued to fall in real terms (adjusting for inflation). And the continuing real-terms cut comes after a 14 per cent fall in real terms spending in the last parliament, the think-tank adds.

“There are 11,000 fewer firefighters in England since 2010, and last year deaths in fires increased by 20 per cent.” Jeremy Corbyn

The number of firefighters has actually fallen by around 8,500 (full-time equivalent since 2010. Labour told us that Mr Corbyn meant fire service staff overall, who have indeed dwindled by more than 11,000.

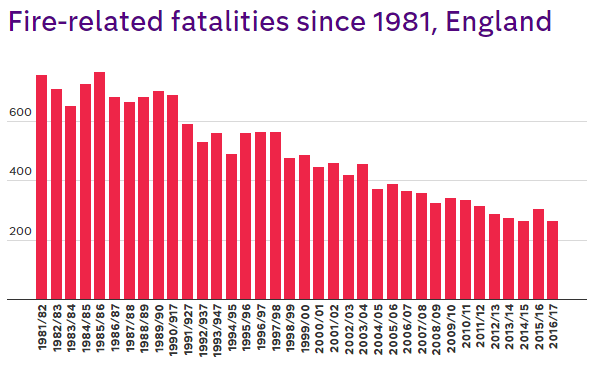

Has this cut come during a time of rising threat to life from fire? Not if you follow the long-term trend in the figures.

Annual fire deaths in England have actually been falling consistently for decades, as this graph shows (the original figures are here):

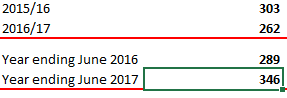

Mr Corbyn’s claim about a rise in deaths is true if you zoom in on a very specific time period – the year ending June 2017, compared to the previous 12 months:

This means the victims of the Grenfell Tower disaster in June are included in the figures, which massively increases the overall death toll for England in 2017.

“Crime is up, violent crime is up.” Jeremy Corbyn

“In fact, crimes traditionally measured by the independent crime survey, are down by well over a third since 2010.” Theresa May

These statements sound completely contradictory, but they reflect the simple fact that there are two main measures of crime in this country, and they tell us different stories.

Jeremy Corbyn is quoting statistics recorded by the police, and it’s true that in those figures, overall crime and violent crime are on the rise.

Theresa May prefers to quote from the Crime Survey for England and Wales, which says the opposite: crime – including violent crime – is falling.

The two data sets measure different things, and both have their weaknesses.

The Crime Survey is based on a questionnaire, with members of the public asked whether they have been the victim of a crime, regardless of whether they have gone to the police or not. Police figures can only show crimes that have been reported.

The figures Mr Corbyn relies upon are considered so unreliable as a true measure of crime that they lost their designation as an official national statistic in 2014, although they are still published alongside figures from the crime survey.

ONS statisticians say rises in police recorded crime reflect a number of factors including “continuing improvements to recording processes and practices, more victims reporting crime, or genuine increases in crime”.

Mrs May prefers the survey – but this does not count some of the most serious crimes like homicide, and sexual offences aren’t recorded in its main tables.