This must be a difficult time for the organisers of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.

There is talk of the small but wealthy Gulf state being stripped of the competition, amid allegations of corruption at world football’s governing body Fifa.

If the World Cup does take place in an Arab country for the first time, claims of exploitation and mistreatment among the migrant workers building the infrastructure in Qatar are unlikely to go away.

A recent graphic from the Washington Post suggested that as many as 1,200 migrant workers have died in Qatar since 2010, compared to handfuls of deaths before other recent global sporting events.

A number of media outlets worldwide – including Channel 4 News – repeated that figure of 1,200 deaths.

But the government of Qatar has responded angrily to both Channel 4 News and the Washington Post, saying the number was “completely untrue”.

Following a detailed examination of all available data, we think Qatar has a point, but still has a lot of questions to answer about migrant workers. Here’s why.

The analysis

About 2.2 million people live in Qatar. About 1.4 million are migrant workers, most from South Asian countries. That’s among the biggest ratios of migrants to citizens in the world.

The biggest expat group are Indians, who number about 500,000. There are thought to be around 400,000 people from Nepal working in the country.

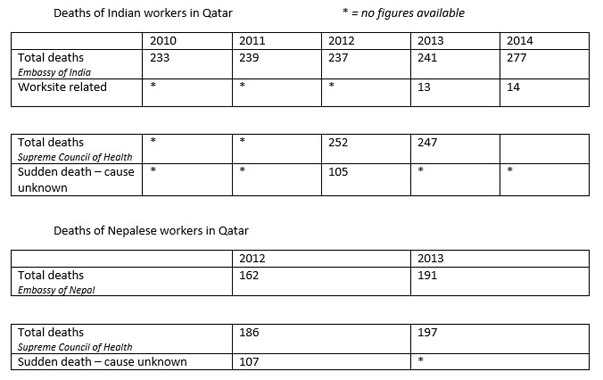

It’s true to say that at least 1,200 workers from India and Nepal alone have died in Qatar since 2010, based on figures released by the local embassies of both countries. Alternative figures from the Qatari Supreme Council of Health are similar.

But it must be unfair to blame the World Cup for all these deaths.

For a start, construction work on the football stadia that will host the competition only started in 2014.

Human rights activists say you should take into account wider construction work as well, because hotels, offices, roads and so on are all part of a drive to transform the country ahead of the flood of foreign visitors expected in 2022.

But it’s impossible to say exactly how much construction work would have happened anyway, even without the World Cup.

In any event, the source of the “1,200 dead” figure – which originates in this 2013 report by the International Trade Union Confederation – is simply the total deaths among the Indian and Nepalese migrant population, not deaths from accidents alone or just deaths among construction workers.

So how many people have died while working specifically on World Cup projects? We don’t know.

Qatar says the answer is none. Zero.

It has to be said that no one FactCheck has spoken to could come up with any evidence to disprove this.

There are any number of quotes out there like the one in this report from the German newspaper Die Welt: “Eight weeks ago, Hamid tells, a worker fell to his death from the roof of a building on an adjacent construction site. In November a man had been burned to death in a fire.”

But this is hearsay, the kind of evidence that wouldn’t stand up in a British court, and it’s not clear whether the “adjacent construction site” had anything to do with the World Cup.

Amnesty International says it has “no reason to doubt” the claim that no lives have been lost on World Cup construction sites, although it argues that we need a broader definition of Cup-related building work, saying: “Most major construction projects in Qatar relate to the World Cup.”

On the other hand, there is widespread doubt about the accuracy of death figures previously put out by the Qatari government, which does not publish regular independently-verified statistics on worker-related injuries and fatalities.

In a letter to Human Rights Watch in 2013, Qatar’s Labor Ministry said: “Over the last three years, there have been no more than six cases of worker deaths. The causes are falls.”

Six workplace deaths in three years seems suspiciously low.

The law firm DLA Piper, which carried out an independent review of Qatar’s labour laws for the government, found evidence of at least 22 work-related deaths among Indian, Nepalese and Bangladeshi migrants in 2013 alone. That’s out of about 600 total deaths among migrant workers from those three countries in that year.

How dangerous is working in Qatar?

That press release from the Qatari government gives the impression that there is no health risk at all attached to being a foreign worker in Qatar – quite the opposite, in fact:

“Qatar has more than a million migrant workers. The Global Burden of Disease study, published in The Lancet in 2012, states that more than 400 deaths might be expected annually from cardiovascular disease alone among Qatar’s migrant population, even had they remained in their home countries.”

But this looks to us like another example of dodgy statistics.

The Embassy of Nepal said 191 Nepalese workers died in 2013, adding that “most deaths were a result of cardiac arrest”, according to DLA Piper.

A former Nepali ambassador to Doha has put a more precise figure on the proportion of migrant worker deaths attributable to “sudden” heart attacks: 55 per cent.

This is back-of-envelope stuff, but let’s say there are indeed about 100 sudden cardiac deaths out of 400,000 Nepalese workers.

The Qatari argument is that this is better than the figures for Nepal.

Public health expert Professor Martin McKee from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said the Qataris appear to be making two mistakes here.

They seem to be comparing deaths from sudden cardiac death in Qatar with the whole death toll from all cardiovascular and circulatory disease reported in the Global Burden of Disease database.

Prof McKee thinks it would be better to single out one category of heart problem – ischemic heart disease – and narrow the deaths down to the 20 per cent or so of those deaths that occur suddenly.

It’s also misleading to compare the overwhelmingly male and mostly young adult Nepalese population in Qatar with the whole population of Nepal, especially because only those who are healthy will go to work in Qatar.

All things considered, Prof McKee thinks we would expect to see in the order of 12 deaths per 100,000 young Nepalese men a year from sudden heart attacks in their home country. That is a lot less than the 100 or so dying in Qatar.

One explanation for the high numbers has been suggested: unscrupulous employers try to get workers’ deaths signed off as heart attacks so they don’t have to make an insurance payout.

DLA Piper said its researchers had “seen no evidence either to support or refute this”.

Either way, you would want to know what was going on with all the heart attacks, which is why the law firm strongly recommended that the State of Qatar launch an independent study into cardiac deaths among migrant workers.

Data on causes of death is weak, the report adds, as autopsies and post-mortems on people who die sudden and unexpected deaths are forbidden by Qatari law unless a crime is suspected.

As things stand, there are few reliable statistics on workplace accidents and deaths in Qatar.

Qatar’s current health strategy document states: “Qatar’s vast population of male labourers, primarily in the construction industry, has limited access to healthcare services and also operates in hazardous environments.

“Workplace injuries are the third highest cause of accidental deaths in Qatar. As yet, Qatar does not have national occupational health standards or guidelines and there is limited data on workplace-related fatalities.

“However, expert opinion suggests a rate of about four to five fatalities per 100,000 workers, approximately double the rate in the European Union.”

And it is difficult for journalists to gather more information on the ground.

Qatar gets a red rating from Reporters Without Borders, indicating a “difficult situation” for press freedom. Last month a BBC team was arrested and interrogated while trying to talk to migrant workers in the country.

ITV News managed to film Nepalese workers in the country, as well as the families of dead migrants being flown back to Nepal in coffins.

Nepal’s minister for labour, Tek Bahadur Gurung, blamed the heart attacks on a problem of “orientation”, saying workers were dying after suddenly turning on the air conditioning in their living quarters.

The suggestion was that the Nepalese government would be reluctant to criticise foreign “partners” like Qatar given the amount of money sent back by Nepalis working abroad. These remittances made up 29 per cent of Nepal’s entire GDP in 2013/14.

The verdict

It’s possible to have some sympathy with both sides here. The Qataris are justifiably angry that many media outlets – including Channel 4 News – have suggested that more than 1,200 deaths are directly attributable to the World Cup when the truth is far more complicated.

On the other hand, human rights groups are keen to not allow Qatar to stake a claim to the moral high ground over this one statistic, when it faces so many other allegations over the treatment of migrant workers.

These include claims that migrants: are reduced to the status of slaves by the “kafala” sponsorship system which means employers can confiscate passports and withdraw exit visas, effectively them in Qatar; are denied trade union representation; are often not paid in full or on time; are forced to live in cramped accommodation. This is only a partial list.

And let’s not forget that the central problem here is the lack of complete data.

We don’t know how many workers die in industrial accidents each year. We don’t know if the figure is more or less than countries that are not hosting a World Cup. We don’t know which exactly precisely which medical conditions are killing the most migrants.

We don’t know these things because Qatar isn’t telling us.