Historic allegations of child abuse by people in positions of power continue to hit the headlines.

It was revealed this week that Peter Righton, a convicted abuser and leading member of the Paedophile Information Exchange group, helped the Home Office prepare a report on children’s care homes in 1970.

Last month the home secretary, Theresa May, announced a public inquiry into how public institutions handled claims of child sex abuse.

The government says it will announce the membership of the inquiry panel as soon as possible, after the retired judge Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss quit as chairman.

In July police said Notarise, an operation involving officers from every police force in the UK targeting people viewing child abuse images online, had led to the identification of more than 10,000 suspects and 660 arrests.

Just how many actual or potential child abusers are lurking out there? Has Britain got a bigger paedophile problem than other countries?

We’re going to have to pretty much ignore the results from the latest anti-paedophile operation by the National Crime Agency. We don’t know how many of the people arrested will be charged or convicted, let alone precisely what they have done.

It’s too early to say how these numbers will affect the annual figures for sex crimes against children.

But we can look at the long-term trends.

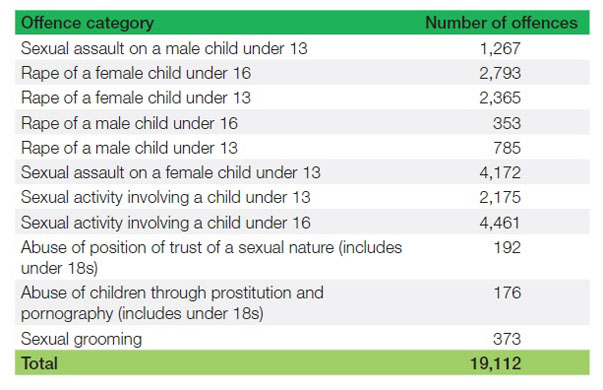

In 2012/13 there were 23,663 recorded sexual offences against children across the whole of the UK. Some 19,112 of those were recorded by police in England and Wales, including 6,296 rapes.

Here’s how the list of crimes breaks down for England and Wales:

According to freedom of information requests submitted by the NSPCC charity, there were 1.9 sexual offences per thousand children in England and wales 2012/13, and the rate has hardly changed in recent years.

The offending rate is higher in Scotland and Northern Ireland and there is some evidence of a long-term rise in recorded child sex crime, although that may be due to changes in the law.

Organisations who work with victims say most sexual abuse of children goes unrecorded, because many victims simply do not report abuse.

It follows that official estimates of the numbers of child sex offenders must be too low as well.

For what it’s worth, the NSPCC found that of 40,345 people registered as sexual offenders in England and Wales on 31 March 2012, 29,837 – almost three quarters – were there for crimes against children.

This is a snapshot and doesn’t tell us much. Not everyone convicted of a sex crime against children will be on the register.

A Home Office study in the mid-1990s found that at least 110,000 men had a conviction for an offence against a child.

In 2000 Det Chief Insp Bob McLachlan, then the head of Scotland Yard’s paedophile unit, extrapolated from this number to suggest that there may have been as many as 250,000 paedophiles living among us, including those not convicted.

‘I was abused’

If recorded crime will tend to under-estimate the scale of abuse, why not take criminal justice out of the equation just ask a random sample of people whether they were abused as a child?

That is what numerous “prevalence studies” have attempted to do.

A widely-cited study by the NSPCC from 2000 estimated that as many as 11 per cent of people surveyed said they had suffered sexual abuse involving physical contact as a child.

In a 2011 follow-up that had dropped to 4.8 per cent. This is why the NSPCC’s current headline on child abuse is that “one in 20 children has experienced contact sexual abuse”.

The big drop between the two surveys probably tells us more about methodological changes the margins of error inherent in these studies rather than a sea change in criminal behaviour.

How do we compare to the rest of the world?

The results from the NSPCC studies are in the same ballpark as prevalence studies from other high-income countries.

An overview of surveys carried out in the US came up with a child sex abuse prevalence rate of 7.5 to 11.7 per cent.

This review of abuse studies from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the US found that 5 to 15 per cent of boys and 15 to 30 per cent of girls and 5 to 15 per cent of boys had suffered some kind of sexual abuse, ranging from incidents that did not involve physical contact all the way to rape.

Rates of recorded crime in different countries are notoriously difficult to compare meaningfully.

Professor Tony Beech from Birmingham University, a leading expert on the treatment of sex offenders, told us: “Personally I see no reason to suggest that things are going to be very different in any other country.”

What causes paedophilia?

What makes a child abuser? How should we define paedophilia? Is it a mental illness, and if so how we should treat offenders?

All of these questions remain highly controversial among scientists, academics and experts who work with abusers and victims.

The World Health Organisation defines paedophilia as “a persistent or a predominant preference for sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children”, adding: “The person is at least 16 years old and at least five years older than the child or children.”

It follows that someone interested in children who may have reached puberty but are still under the age of consent may not technically be a paedophile.

Prof Beech told us he prefers to use the term “ephebophile” to talk about people in that category.

After much hand-wringing, the American Psychiatric Association continues to list paedophilia as a mental disorder, but only if the person “feels personal distress about their interest, not merely distress resulting from society’s disapproval” or has “a sexual desire or behaviour that involves another person’s psychological distress, injury, or death, or a desire for sexual behaviours involving unwilling persons or persons unable to give legal consent”.

In other words, a paedophile who fantasises about children but never acts on his or her desires is not mentally ill, according to this influential body.

Others have suggested that attraction to children constitutes a third sexual orientation rather than a mental aberration, which suggests that paedophiles cannot help the way they feel and attempts to “cure” them are likely to be futile.

Last year a Canadian clinical psychologist, Dr James Cantor, published research that suggested a possible biological explanation.

He found that paedophiles were up to three times more likely to be left-handed or ambidextrous than the average man.

They were shorter than average and had lower IQs. They were more likely to have suffered a blow to the head in childhood and brain scans suggested they had less connective brain tissue called “white matter”.

The assumption here is that factors fixed before birth go some way to predicting a sexual attraction to children.

But this is complex territory. Prof Beech told us that psychological trauma in childhood – perhaps the sexual abuse that is often assumed to make people more likely to offend themselves – can cause physical changes to the brain too.

He recited a long list of potential risk factors – foetal alcohol syndrome; traumatic brain injury; nutrition; genetic traits – all of which are worthy of further research.

Crime and punishment

Just as we don’t know whether child abusers are born or made, we don’t know how to stop them re-offending.

Studies from England, Canada and the US found that around 40 per cent of convicted child molesters tend to re-offend. Those who targeted boys and children outside their own family were more likely to abuse again.

Cognitive behavioural therapy is offered to many offenders in UK jails, although the authorities have also experimented with Prozac-type anti-depressants and so-called “chemical castration” – giving prisoners who volunteer drugs to reduce their sex drive.

The evidence is mixed as to how well these approaches work. Prof Beech told us there was some evidence that treatment works for “middle-risk” offenders but added: “Very fixated paedophiles can’t be cured.”

Some readers might agree with the late MP Geoffrey Dickens that the best way to deal with paedophiles is to “castrate the buggers”. But even that extreme option doesn’t always work.

Voluntary surgical castration – which is still offered to sex offenders in the Czech Republic, Germany and California – has been shown to cut recidivism rates dramatically, but even some castrated paedophiles have been known to carry on abusing victims.