The claim

“There can be no doubt that the drastic cuts in force budgets is doing real harm to the ability of the service to protect the public.”

“There can be no doubt that the drastic cuts in force budgets is doing real harm to the ability of the service to protect the public.”

Steve White, chairman, Police Federation of England and Wales, 29 January 2015

The background

Police officer numbers in England and Wales have fallen to their lowest levels since 2001, according to the latest official statistics.

The Police Federation – the closest thing bobbies have to a union – is outraged, while others note that crime rates have fallen even as forces wrestle with budget cuts.

Just how thinly stretched are the police these days? And should we be worried?

The analysis

The latest Home Office estimates of police strength in England and Wales are for September last year.

The overall police workforce (including officers, PCSOs and staff) dropped from just under 245,000 in March 2010 to just under 208,000 in September 2014.

That’s a loss of more than 36,000 police personnel or, as the Police Federation says, the equivalent of losing nine of the smaller police forces at their 2010 strength. It’s like going from 43 constabularies in England and Wales to 34.

Forces have cut police staff more than officers, but officer strength has also fallen considerably – from 143,734 to 127,075 or by 11.6 per cent since March 2010.

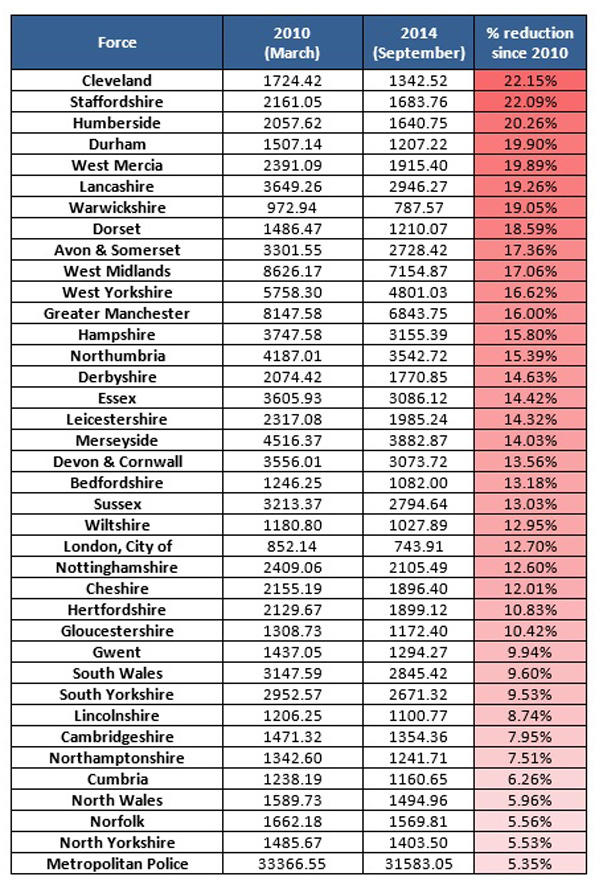

This is figure for England and Wales and there is considerable regional variation. This is the Police Federation breakdown for cuts to 38 out of the 43 forces:

Some forces have seen officer numbers drop by more than 20 per cent.

Britain’s biggest force, the Metropolitan Police, has managed to protect officer numbers from the cuts to a certain extent, although there are still fewer than the 32,000 or so officers promised by the mayor of London, Boris Johnson, while he was running for election.

Bobbies on the beat

While there is no dispute that police officer numbers are down, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary reckons forces have managed to shift a bigger proportion of them into frontline roles.

The police watchdog estimates that 93 per cent of officers left after the cuts will be deployed on the front line, rising from 89 per cent in 2010.

According to the House of Commons Library, the overall effect is that frontline officer numbers have still been falling overall, but less sharply.

This suggests that forces have taken steps to minimise the effect of the cuts on the public, although these figures of course relate to the number of officers on the payroll, not the number available at any given time.

If you need a bobby right now, how many will be available?

The Police Fed has given Channel 4 News an interesting snapshot of how many officers were actually on duty in 11 forces across England and Wales at a random time – 11am yesterday.

The Fed’s numbers include uniformed personnel only, not detectives. They only count people who are actually on duty, not training and so on.

There is a huge variation in how many officers are available compared to the size of the local population.

At 11am on Monday, there were 4,136 uniformed officers on duty in the Met Police area. That’s about one police officer for every 1,740 residents.

In Greater Manchester there were 398 officers on call – or one officer covering 6,281 Mancunians.

And in Kent there were only 203 officers on shift covering a population of 1.7 million, or one officer between 8,374 people.

This is only a snapshot, and we don’t have historic figures to compare it with, so we don’t know whether officers are generally more thinly spread than they were in 2010.

Does it matter?

The Association of Chief Police Officers noted that crime rates have been falling throughout this time of austerity, saying: “Our effectiveness can’t be solely measured on police numbers. It is the service we deliver that matters to the public.”

Has crime really fallen? That is what police figures say, but there is a growing chorus of scepticism about the numbers recorded by forces.

Nevertheless, figures from the Crime Survey for England and Wales, collected independently from the police, agree crime has been falling in England and Wales over the last 10 years or so, as it has in a number of other western countries.

And independent data from health services appears to show that violence is on the decline in England and Wales. Again, this is in line with trends in a number of other countries.

It may seem strange that crime should fall as police dwindles, but there is actually little consensus among the experts about what drives long-term changes in crime rates.

Criminologist Ben Bradford reviewed the available evidence in 2011 and concluded: “It is too early to say… that there is a direct causal link between higher numbers of police and lower crime.”

Some studies have found a link between higher police numbers and falls in property crime, but establishing cause and effect is a difficult task.

The verdict

There is little dispute about the scale of the cuts dished out to police forces since 2010. The total police workforce in England and Wales has fallen by about 15 per cent and the number of officers has been cut by more than 11 per cent.

But there is some evidence that forces have risen to the challenge by putting more officers in frontline roles.

The Police Federation’s snapshot of police officers on call yesterday is an insight into how thinly stretched some forces are – but we don’t know whether the ratio of available officers to members of the public is getting better or worse.

The government may well take some solace from the fact that crime, on all the evidence, is falling.

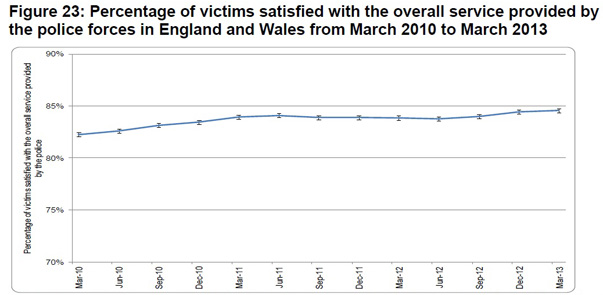

Several measures of public satisfaction with the police also rose slightly over the first three years of austerity, according to HMIC:

Rather than disputing any of this, the Police Federation says crime rates are only part of the story.

Chairman Steve White said: “We hear that crime is falling but this only measures a snapshot of police activity.

“What we do not hear about is the extreme pressure these government cuts are placing on officers’ ability to prevent terrorist attacks, manage sex offenders in the community, protect children from sexual exploitation and return missing persons to their families among other key issues.”