The claim

“Public sector pay since the great recession has increased by more than pay in the private sector.”

“Public sector pay since the great recession has increased by more than pay in the private sector.”

Francis Maude, 10 July 2014

The background

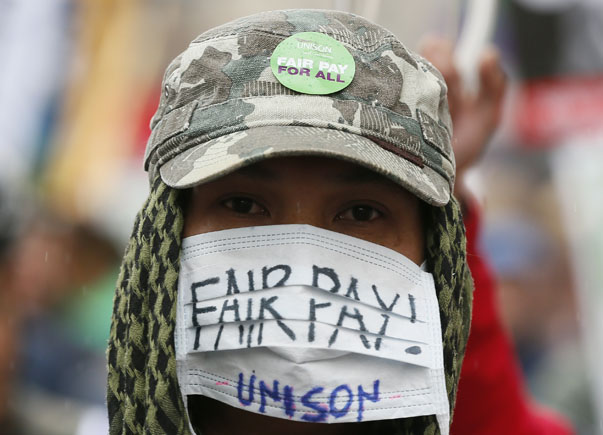

More than 1 million people are thought to be taking part in the biggest strike to hit the Conservative-led coalition.

Teachers, firefighters, civil servants, transport workers, refuse collectors, librarians, dinner laders, caretakers and cleaners all joined in the one-day walkout, protesting against cuts to public sector pay, pensions and jobs.

But the cabinet office minister, Francis Maude, said public sector workers have actually done better than their counterparts in the private sector since the downturn began, suggesting that the strikers’ anger is misplaced.

Is he right?

The analysis

The short answer is yes. There are a number of different ways of tracking pay growth, and most of them prove Mr Maude right. But the bigger picture is complex.

If we look at Office for National Statistics (ONS) data for average weekly earnings, and start counting in the first month of official recession (April 2008), we find that public sector pay has grown slightly more, whether you include bonuses or not.

Alternative figures for gross hourly, weekly and annual earnings from 2008 to 2013 tell the same story: earnings growth has been higher in the public sector.

Hang on a minute though. If we pick one of these data sets – median hourly earnings excluding hourly overtime – there’s a massive difference between the average pay of a public and private sector worker in 2013: £15.22 an hour compared to £11.98, nearly 30 per cent more.

That doesn’t seem credible, and indeed it isn’t a fair comparision. Raw data like this is misleading, because the people who work in the public and private sectors are very different.

Public sector workers tend to be older, more highly skilled, and better educated. Women are more likely to hold higher positions in the public sector.

All these things mean we would expect people in the public sector workforce to earn more anyway.

The ONS tries to strip out the effects of these things with regression modelling. Once the ONS adjusts for the demographic differences, it finds that on average, pay in the public sector is between 2.2 per cent and 3.1 per cent higher than in the private sector.

But use a different model and you get dramatically different results. If you adjust for size of employer (working on the principle that bigger organisations tend to pay more, and most public sector workers work for a big organisation) you end up finding that the public sector gets paid slightly LESS.

So there are any number of ways to skin this cat. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) sets out its methodology here, and the think-tank Policy Exchange has a go here.

The different techniques mean they all come out with slightly different numbers, but many economists agree that there is usually a pay gap, with the public sector getting slightly more.

This is sometimes called a “public sector premium” and it’s been with us for years.

The IFS told us it’s probably best not to get too hung up on the numbers here, but follow the changes over time to see what’s happening. If we do this, a clear picture emerges.

The pay gap widens sharply in about 2008, because private sector pay fell sharply as the economy went into recession. But many public sector workers’ wages were protected by pay deals covering the period 2008 to 2011, so their earnings held up.

After 2010 the gap narrowed as the economy recovered and the government imposed pay restraint on state workers.

The indication now is that the pay gap has just about returned to its pre-recession levels, and it will shrink even more if the government continues to impose pay restraint on state workers, while wages grow more quickly in the private sector.

It’s worth noting that the very lowest paid workers were spared the worst of the pay cuts. The ONS reckons that if you look at the lowest-paid 5 per cent, public sector workers earned on average about 13 per cent more than private sector workers in 2013 after allowing for demographic differences.

The verdict

Naturally, reality is more complicated than these neat statistics and they miss a few important things.

There are massive regional variations. In Northern Ireland public sector workers earn 15 per cent more. In London the pay gap disappears altogether: private sector workers do better.

The ONS numbers don’t included private sector perks like company cars and health insurance. But equally, they don’t take into account the value of more generous public sector pension schemes.

Nevertheless, official statistics suggest that: public sector workers are on average tend to be better paid than their counterparts in the private sector; wage growth has been higher in the public sector since 2008; the government offered some protection to the lowest paid when it introduced pay restraint after 2010.

All of this suggests the unions have a stronger case when they protest about the massive job losses sustained by the private sector, rather than complaining about earnings per head.

What of the future?

As the graph above shows, the IFS reckons the pay gap will narrow dramatically in the next few years, making the public sector a much less attractive place to work.

This will create a dilemma for the next government, whatever its political make-up.

The think-tank says: “Some public sector employers may well find it increasingly difficult to retain and recruit high quality workers…if that leads the government to want to mitigate the squeeze in public sector pay but to keep workforce costs as planned it would have to absorb even more cuts to the size of the workforce.”