The awkward subject of Britain’s colonial past is dogging David Cameron during an official visit to Jamaica.

The country’s prime minister Portia Simpson-Miller raised the subject of a campaign to get European countries including the UK to pay for the historic crimes of the transatlantic slave trade.

Mr Cameron has said he does not believe in paying reparations to countries who were affected by slavery.

But Caricom, an organisation representing 15 Caribbean states and dependencies, has approved a ten-point action plan calling for “reparatory justice for the victims of genocide, slavery, slave trading, and racial apartheid”.

What was Britain’s role in the slave trade?

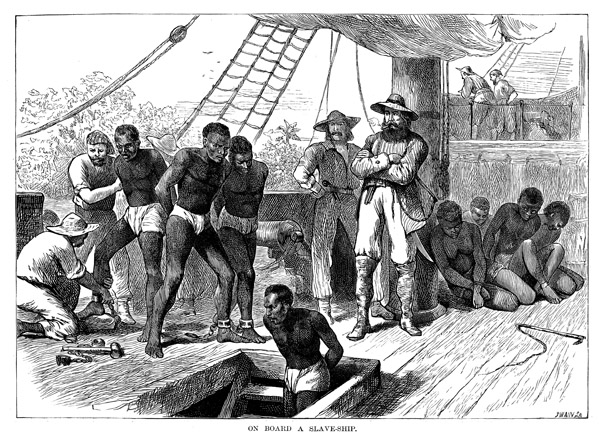

The traffic in Africans began in in the reign of Elizabeth I, and Britain was probably the world’s leading slave trader until slavery was abolished in the 19th century.

The so-called “triangular trade” saw merchants trading goods for slaves with local rulers in Africa, then shipping slaves – in appalling conditions – to European colonies in the Americas, where they worked on plantations or in domestic service.

Estimates of the number of African people transported across the Atlantic alive range from 9 million to 17 million. Millions more died in transit.

British ships alone carried 3 to 4 million slaves over the centuries, according to some historians.

The trade in slaves was finally outlawed in the British Empire in 1807 after decades of campaigning by abolitionists like William Wilberforce. Royal Navy ships began patrolling the Atlantic routes in an attempt to stop the human traffic.

But slavery was not fully abolished until 1833, and it took five more years for slaves to become fully free across territories controlled by Britain.

Famously, handsome reparations were paid – but not to the newly freed men, women and children. Instead, the British government borrowed £20m – a staggering sum equivalent to about 5 per cent of the national wealth – to compensate former slave owners.

The descendants of those who were paid off include David Cameron, former cabinet minister Douglas Hogg, George Orwell and Twelve Years a Slave actor Benedict Cumberbatch, according to a database put together by academics at University College London.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the US constitution abolished slavery in 1865 and in 1869 Portugal, historically Britain’s biggest rival in the “nefarious trade”, finally freed all its slaves.

What do the campaigners want?

Last year the Caricom nations approved a ten-point action plan for slavery reparations.

Not all of the points involve money. The campaigners also want full formal apologies from the governments of European countries involved in the slave trade, saying “statements of regret” are not enough.

And they want a repatriation programme, offering the descendants of slaves the chance to return to their ancestral homelands in Africa.

But many of the points involve cost. European countries are being asked to cancel oustanding debts and fund programmes promoting healthcare, literacy, “psychological rehabilitation” and access to technology for people in the Caribbean.

It’s clear that some of these demands concern the broader legacy of colonialism rather than just slavery. Point six states: “The British in particular left the black and indigenous communities in a general state of illiteracy. Some 70 percent of blacks in British colonies were functionally illiterate in the 1960s when nation states began to appear.”

Caricom comprises the former British colonies Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat , Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Trinidad and Tobago, as well as Haiti and Suriname, which were ruled by the French and Dutch.

The action plan was unanimously approved by member states and is addressed to “the Governments of Holland, UK, France as well as potentially other nations who profited from the slave trade”.

Sir Hilary Beckles, chairman of the organisation’s Reparations Commission, has said the campaign is not about “cash handouts” but “public health, education, poverty eradication, institutional and cultural racism, debt relief, and support for the repatriation of those Africans who wish to return to Africa, and support for development programs for First Nation peoples”.

“The cost of these development programs should be supported by European nations within the context of a reformed development paradigm.”

The campaigners are focusing on the impact of the historical crime on communities today, not suggesting that individuals whose ancestors were victims of slavery should be given compensation.

Of course this raises the possibility of a British taxpayer of Afro-Caribbean descent – who may be the descendant of slaves – paying compensation to countries where the white descendants of slave owners still live.

Are all the former Caribbean colonies poor?

No. According to the World Bank, Trinidad and Tobago has a higher GDP per capita than a number of EU member states including Portugal, Greece and Cyprus.

But the poorest Caricom member state, Haiti, languishes at the bottom end of the league tables for national wealth.

Britain already gives aid to Caricom members. Payments worth just over £200m in bilateral “official development assistance” were made to the various nations and dependencies between 2009 and 2013.

Is there a legal case?

It’s hard to say, as this is not a lawsuit yet.

Caricom is being “advised” by the law firm Leigh Day, who in 2013 managed to get the British government to pay nearly £20m in compensation to Kenyans tortured and mistreated during the Kenyan Emergency of the ’50s.

But at the moment no legal action has been launched over slavery reparations, nor is it clear what the legal route would be.

Caricom is calling for European governments to enter into negotiations with them, but so far no country has accepted an invitation.

The current British government’s position is that reparations are not “the answer”. David Cameron told the Jamaican parliament today he hoped “we can move on from this painful legacy”.

Is there a precedent for reparations?

Certainly, countries have in the past made payments in respect of historical crimes.

Germany paid compensation to countries its forces had occupied during World War Two, including Greece and Poland.

West Germany also made payments to Israel in the 1950s and 1960s in respect of the murder of Jews and theft of their property during the Holocaust.

The United States government paid reparations to Japanese-Americans interned in World War Two, and Britain was ordered to compensate veterans of the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya more than 50 years later.

But all these cases involve victims who were still alive when the claims were made. It’s much harder to find examples of payments made in respect of the crimes carried out in the more distant past.

The US federal government has agreed to pay billions of dollars to Native Americans. This was over the historic mismanagement of land ceded to Washington under various specific treaties dating back to the 1800s, rather than for general wrongdoing.

Who has apologised for slavery?

In 2009 the US Senate approved a resolution apologising for slavery. US states like Virginia, Alabama, Florida, Maryland, and North Carolina have also issued statements of remorse.

In 2006 Tony Blair expressed “deep sorrow” for Britain’s role in the horrors of slavery, but stopped short of issuing a formal apology.

The governments of West African states Ghana and Benin have apologised for the part their forebears played in the trade.

In 2009 a Nigerian human rights group called for traditional African rulers to apologise for colluding with European slave traders, to little effect.