It has been two years since Alan Kurdi, a three-year-old boy from Syria, was found washed up on a beach in Turkey.

Photographs of the dead toddler (who’s name was initially reported as Aylan Kurdi) sparked international outrage, highlighting the plight of migrants crossing the Mediterranean to reach Europe.

But two years on, has the migration crisis improved or changed? And how many more people have died?

How many people are making the crossing?

The number of migrants arriving in Europe after crossing the Mediterranean has gone down dramatically since 2015.

On average, 84,663 people landed on European shores each month in 2015.

That average has dropped to 15,494 per month so far in 2017.

2015 stood out as a year with extremely high levels of sea crossings.

There was a huge drop in arrivals between 2015 and 2016 – but that was coming from an unusually high peak.

So although there are now significantly fewer people crossing the Mediterranean than there were in 2015, the rate of change has slowed.

Who is crossing the Mediterranean?

The geography means that certain nationalities of migrants favour different routes across the Mediterranean.

For instance, so far this year, Syrian people made up the single largest group of migrants landing in Greece. But, of those landing in Italy, the most common nationality is Nigerian.

Overall, people come from a very wide range of different countries, with no single nationality accounting for more than 15.1 per cent.

The vast majority are men, with children making up nearly 17 per cent of all those making the crossing.

The UNHRC says that in the first seven months of 2017, some 13,700 children arrived to Italy by sea. Of these, 92 per cent had travelled alone.

Where do migrants arrive?

Between January and August 2017, nearly 124,000 individuals landed on the shores of Europe after crossing the Mediterranean.

The vast majority of them landed in Italy, which has received more than 99,000 people.

Greece, Spain and Cyprus also receiving significant numbers.

How many deaths are there?

Since the death of Alan Kurdi in 2015, at least 8,500 people have either died or gone missing while trying to cross the Mediterranean.

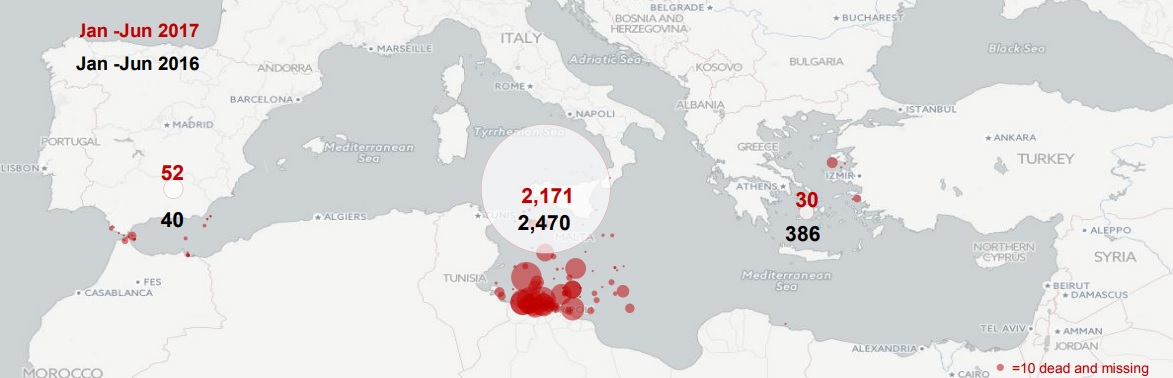

The Central Mediterranean region sees by far the highest numbers of migrants dying or going missing.

This year alone, some 2,171 people were reported dead or missing in the area near Italy and Tunisia. This compares to 52 in the western Mediterranean and 30 in waters around Greece.

This is not surprising since Italy also sees the largest number of arrivals.

Although the overall numbers of people being reported dead or missing have gone down, the success rate of getting across the Mediterranean has actually got worse.

According to the UNHRC, 1.86 per cent of individuals crossing in this region died or went missing in 2015. Now, that figure has grown to 2.53.

But what is not clear is why this rate has changed. It is possible that authorities are simply getting better at recording these statistics, without so many deaths slipping under the radar. Alternatively, the figures could represent increasing levels of danger.

The reality is likely to be down to numerous different factors.

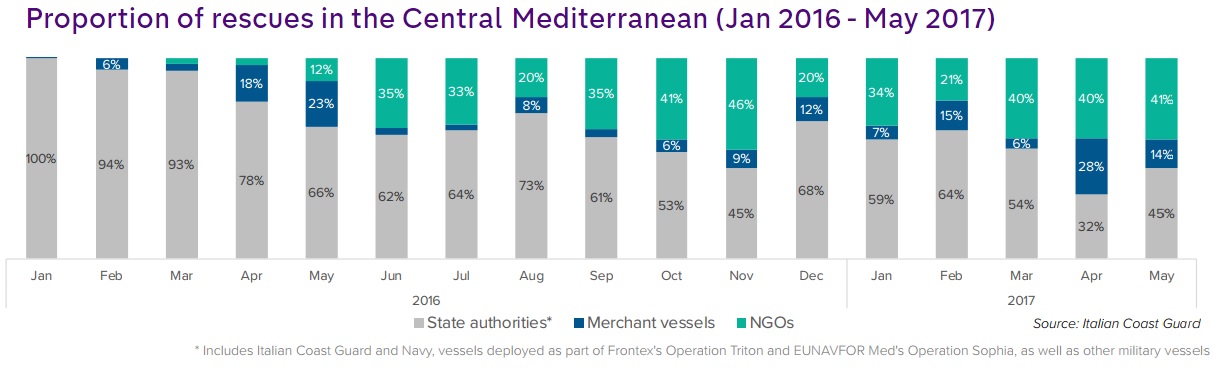

However, what we do know is that rescue missions are increasingly being run by NGOs rather than state authorities.

In May 2017, 41 per cent of all rescue missions on this dangerous Central Mediterranean route were done by NGOs. That’s compared to just 12 per cent in May 2016.

Meanwhile, the role of state authorities has dropped from 100 per cent at the start of 2016 to less than half by May 2017.