The government’s high speed rail project, HS2, has come under repeated criticism for bad planning and wasting money.

Even the Department for Transport’s own former Chief Scientific Adviser, Professor Roderick Smith has called for a “root-and-branch review” of the whole project, saying: “We’re making so many fundamental mistakes.”

Speaking to FactCheck, Smith said: “I am really concerned with the way it’s developed and I think an incredible number of completely inept decisions have been made which will add to the cost, decrease the utility and frankly bring the project into almost a laughing stock.

“I was chief scientist at the Department for Transport, for a time, during the gestation period of the project. Nobody wanted to listen to me. They hired me as their expert to give advice – they didn’t want to listen.”

So what’s actually going on with HS2? And how does it compare to other high speed rail projects across the world? FactCheck looked into the details.

How much will it cost?

When HS2 was first given the green light in 2012, the government said they expected it to cost £32.7bn. But that figure has now shot up to £55.7bn.

Officials say the increase down to inflation and contingency funds to cover any unexpected costs. But the project is facing cost and time pressures. In fact, last year the National Audit Office said there was only a 60 per cent chance that the first phase of the HS2 would be completed on time.

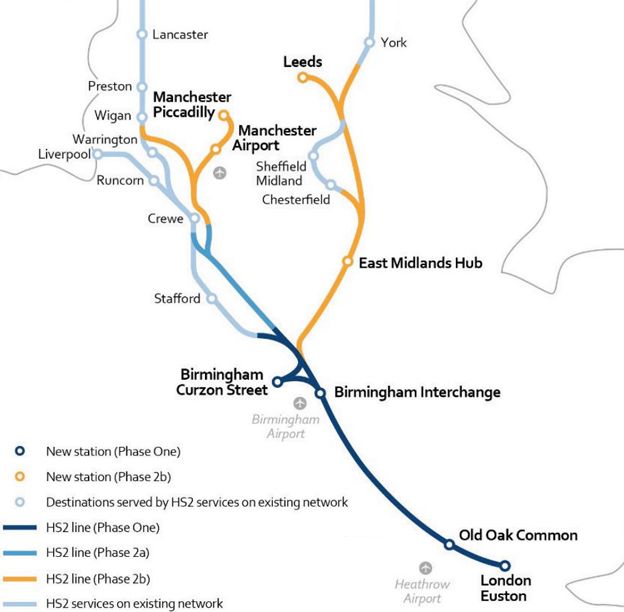

When both phases of the project are complete, the track will cover 531km stretching from London up to Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and other cities. This means the total cost is equivalent to £104.8m per kilometre.

By contrast, the most expensive high-speed line in France was the LGV

Méditerranée which opened in 2001. That covered a distance of 250km with a total cost of just £16.9m per kilometre. That makes Britain’s HS2 project around six times more expensive.

The contrast is even more stark when compared to France’s original high-speed track – the LGV Paris-Lyon line, which opened in 1983. As the country’s cheapest high-speed line it cost just £4.7m per kilometre, more than 22 times less than HS2.

But the comparison isn’t quite fair, mainly because the total costs cover different things. For instance, the UK project will include massive expansions of train stations, which has not always been needed elsewhere.

Will HS2 be the world’s fastest bullet train?

There is a common myth about HS2. Media reports have repeatedly claimed that it will run at a top speed of 400km per hour. For instance, the Independent has said it “will potentially see trains run at 250 mph (400km/h) from London to Birmingham from 2026”. The BBC, the Guardian and others have made the same claim.

But HS2 told FactCheck that there are actually no plans to operate at this speed. What’s more, they say this was never the plan. Indeed, the track, control systems and trains being purchased are not physically capable of it.

The confusion has arisen because HS2 says it has allowed enough flexibility to potentially do a major upgrade of the line at some point in the distant future, should the government want to. The curves in the route could theoretically see speeds of up to 400km per hour.

For now, though, the plans are to have a top speed of 360km per hour. But most journeys will not exceed about 320km per hour, unless the train needs to catch up on lost time.

However, Jonathan Tyler, an academic and leading transport consultant, told us that even these plans are controversial. He said it had become clear that “everywhere else in the world that 320 is being accepted as the norm”. A top speed of 360km per hour for HS2 is “probably very optimistic”.

So are the government being too ambitious?

A parliamentary report in 2015 compared high speed lines in different countries. According to this, the top speed in Germany, Italy and Spain is just 300km per hour. In Japan and France, it’s 320.

In fact, the only high speed network with a top speed similar to HS2’s is in China, where trains can reach 350km per hour – still less than HS2’s 360.

However, it is worth remembering that these were 2015 figures. Improvements to networks are likely to push up the maximum speed in some countries. HS2 does not anticipate being the fastest network once it is up and running. Indeed, Japan has already test-run a new bullet train, powered by electrically charged magnets, which reached an incredible 603km per hour.

Should bullet trains terminate in city centres?

The main HS2 station in London will be near the city centre. But critics have pushed for a more out-of-town terminus, saying it will save money.

Coming into London, the bullet train will stop at Old Oak Common station first, in West London. But it will then continue on to make the short journey to Euston station.

To accommodate HS2, the existing station at Euston will be expanded to have 11 new platforms – six will open in 2026, and another five in 2033. HS2 says this provides far greater benefits: stopping at Old Oak Common takes pressure off Euston, but the service will also allow passengers to go straight to the centre of London, rather than having to rely on local shuttle services.

But many critics say that this is a waste of money. “Wherever you get near the city centre, the costs of construction go up exponentially,” Professor Smith told FactCheck.

“The bit from Old Oak Common to Euston will be very expensive to build. It will be very slow running through tunnels; there’ll be lots of curvature on it that high speed trains don’t like. It just doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. The experience in Japan is not to go to the existing city centres.”

Professor Tony May, Emeritus Professor in Transport Engineering at Leeds University, said that China was doing the same. “Everywhere they’re building their high speed lines, they’re putting the stations 5-10km from the centre of the city, and using local transport to provide the local connections,” he said.

This part of the debate largely comes down to whether you think the convenience of building the track to Euston is worth the extra cost. Experts are divided, but there are no right or wrong answers.

How about the frequency of trains?

On HS2, there will be 18 trains an hour. Each train will be 400m long, carrying 1,100 people. That’s roughly equivalent to three jumbo jets’ worth of people.

Compare that to the Nozomi line within Japan’s famous Sinkansen high speed rail network. That line runs just ten trains per hour, but each train has a slightly larger capacity of 1,323.

Services in France are also less frequent than what is proposed with HS2, even when we take into account future upgrades. The high-speed line between Paris and Lyon, for instance, currently runs up to 13 trains an hour. There are now plans to increase this to 16 by 2030, but this is still less than what is being proposed with HS2.

Some are sceptical that this can be achieved. “They are being very optimistic,” said Tyler. “It could happen, but it’s a pretty high risk because if they can’t achieve it – and a number of us with timetabling experience are sceptical – then the businesses case is seriously undermined.”

So how long will each HS2 train be sat in the station for, before it sets off again?

HS2 did not give us a precise turn-around time, but said it would be about 20 minutes for each train. However, here at FactCheck, we are a little sceptical of this claim.

If turnaround time really is just 20 minutes, then surely each platform could accommodate three trains per hour? With 18 trains an hour, that means Euston station would only need six high-speed platforms.

Yet HS2 is building 11 platforms – at a huge extra cost. By our calculations, this allows for a far longer turnaround time of over half an hour.

So why the extra platforms? HS2 told us it was partly because of the gap needed between one train leaving the station and the next arriving.

But they admitted that their plans do also allow for turnaround times to be extended in certain circumstances, such as when there are delays, technical problems or passenger issues.

Will it boost local economies?

This is a matter of much debate. Different studies have estimated the economic boost from HS2 at everything from £15bn to just £0.01bn per year.

However, examples from other countries suggest that high-speed rail is not necessarily enough to transform local economies on its own, and extra localised policies and funding help.

“All the evidence from the continent suggests that, if there are economic benefits, they will be within five to ten miles from the station,” says Professor May. “Places like Blackburn, Burnley and maybe even Bradford are unlikely to benefit unless there is additional local investment – which then further adds to the cost.

“The only way that places like Lille and Lyon have benefited from the TGV network is by putting substantial additional investment into the areas around the station.”