The Grenfell Tower fire has drawn attention to the state of council housing in this country.

Are we spending enough on building and maintaining social housing?

It’s a complicated issue – here’s what we know and what we don’t know.

Who pays for new social housing?

People often refer to socially rented homes as “council houses”, but new builds are often funded by central government and run by not-for-profit housing associations.

Since the 1970s, successive governments have generally spent less on building social housing, partly because fewer people live in council houses.

About one in three people in Great Britain lived in social housing in the early 1980s. By 2011 it had fallen to about one in six.

Census data from that year reveals that 4.1 million households out of the UK’s 23.4 million families rent from councils or housing associations.

Why are fewer people living in social housing?

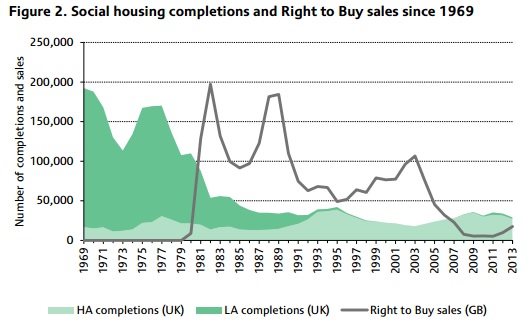

Since the 1970s Britain has been building fewer homes for social rent and selling off existing properties (graph – Institute for Fiscal Studies):

Margaret Thatcher launched Right To Buy in 1980. Tenants were given the right to buy their council homes at a large discount.

By 2013, more than 2.5 million homes had been sold to tenants, effectively transferring large amounts of housing from the public to the private sector.

Over the same period, the numbers of social homes built plummeted, and many local authorities stopped building homes altogether.

Instead, successive governments preferred to pay Housing Benefit to low-income tenants renting from private landlords.

The Conservative-led coalition promised to replace every property sold off under Right to Buy – but had only managed to replace about one in 10 by 2014.

Recent cuts

Despite these long-term trends, the coalition stands out by cutting capital investment in new social housing in England by 63 per cent in real terms.

Government spending on all kinds of affordable housing (social rent and other categories) fell under the coalition after rising under Labour.

Who lives in social housing?

The housing is allocated according to need, so social renters have lower incomes on average than the general population.

They are much more likely to have children, to live alone and to claim disability benefits.

The gap between social tenants and others has widened dramatically since Right To Buy, suggesting that better-off people took the opportunity to buy their home, while poorer tenants stayed in the social rented sector.

Who runs the estates?

Grenfell Tower was being run by Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation.

This isn’t unusual: about half a million homes across 38 councils are run by similar bodies.

To be clear – organisations like KCTMO do not make a profit and many were set up after tenants voted to create them, often after becoming frustrated with dealing direct with councils.

So it’s not right to suggest that the councils like Kensington and Chelsea have outsourced the administration of housing to private contractors – although the renovations to Grenfell Tower were subcontracted to a private company.

Does Kensington and Chelsea spend enough on housing?

The borough’s accounts for the latest financial year show that it owned £755m worth of council housing, spent £15m on building new dwellings and £12m on repairs and maintenance.

The council spent £8.7m on refurbishing Grenfell Tower, part of a wider £67m investment in the North Kensington area.

It’s very hard to know how to put figures like this in context. Councils around the country will spend wildly different amounts on their housing stock, depending on how much housing they have, its age and condition, and many other factors.

Isn’t it one of the richest boroughs?

It depends what you mean. House prices in Kensington and Chelsea are the highest in this country, with the average property going for £1.2m.

The average property costs 30 times what an average local resident earns. This is the highest ratio in England, the national figure being about eight to one.

Kensington and Chelsea is an area where great poverty and wealth collide. It contains areas that fall into the 10 per cent most deprived in England, alongside some of the richest.

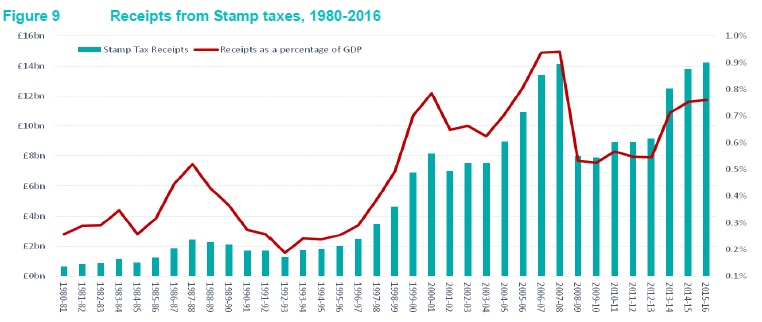

It’s possible to argue that high property prices – and the kind of buoyant housing market that we see in wealthier parts of London – benefit the general population by generating tax revenue for the government.

As a share of the national wealth, the amount brought in by stamp taxes (on property sales) are at record highs.

In 2015-16, the local authority with the highest stamp duty land tax receipts from residential property transactions was Kensington and Chelsea. The borough brought in £514m to the Exchequer, or 7 per cent of all SDLT receipts.

But this windfall has not been distributed to local authorities. Between 2009/10 and 2014/15 central government grants to local government were cut by 36 per cent.

Urban councils like London boroughs were harder hit than rural counties.

Some local authorities raised council tax to try to mitigate cuts from Whitehall, but many chose not to raise taxes, taking advantage of central government incentives.

Last year most London boroughs raised council tax rates after freezing them in cash terms for years.

Kensington and Chelsea opted to raise its rate by 1.8 per cent, a lower increase than 28 out of 32 London boroughs.

The top rate of council tax for Band H properties in Kensington and Chelsea is £2,124.04, the fourth lowest in London.