Education is fast becoming a key election issue. Both Labour and the Lib Dems say that schools are facing a funding crisis, and have pledged to boost school budgets by billions of pounds.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives have defended their record, saying that school budgets are already protected.

FactCheck took a look at the figures.

Are school budgets protected?

The Department for Education has protected its core schools budget in real terms. So spending will go up every year, with a minimum requirement to match inflation. Under current plans, £42.6bn will be spent in 2019-20, up from £39.6bn in 2015-16.

But, as usual, it’s not as simple as that.

Although the overall core budget is protected, the spend-per-pupil is not. And the government’s funding plan is not nearly enough to keep up the levels of spending for each child.

The National Audit Office (NAO) identified two main reasons for this.

First, the number of students is increasing. Government figures show there will be an estimated 458,000 extra pupils in the school system by 2019/20. That’s an increase of 3.9 per cent in primary schools and 10.3 per cent in secondary schools, over five years.

So the pot of money assigned to schools is being shared out between more and more pupils. The IFS says this equates to a real-terms cut of around 6.5 per cent, per pupil, between 2014–15 and 2019–20.

This is compounded by the fact the government’s spending plan doesn’t take a whole range of rising costs into account. These include higher employer contributions to national insurance, the introduction of the national living wage and the apprenticeship levy.

In order to pay for all this, schools will have to find £3 billion of savings by 2019-20.

All together, this means the average real-terms spend per pupil will fall by 8 per cent between 2014-15 and 2019-20. That’s according to both the IFS and the NAO.

The NAO said: “Schools have not experienced this level of reduction in spending power since the mid-1990s.”

How about other funding pressures?

As budgets tighten, schools are already seeing some resources being stretched.

Since the Conservatives got into government in 2010, it’s become more common for infants to be in large classes, of more than 30 pupils. The percentage of kids in large infant classes has risen by 3.6 percentage points since 2010 and is now at 5.8 per cent.

In other schools, these figures have risen less dramatically, but were already much higher. Since 2010, the number of primary pupils in large classes rose from 11.7 to 12.9 per cent. And in secondary schools it inched from 10.2 to 10.3 per cent.

There are also concerns over teacher recruitment. So far, the number of teachers has roughly kept pace with rising pupil numbers. But last year the recruitment of postgraduate trainees at secondary levels was 11% below the government’s target. Recruitment levels for teachers of subjects like maths, physics, computing and design technology were particularly low.

Schools have also been affected by other corners of the public sector, such as the provision of school nurses. The latest NHS figures show that the number of school nurses has fallen by 14.5 per cent since May 2010.

Is there a funding crisis?

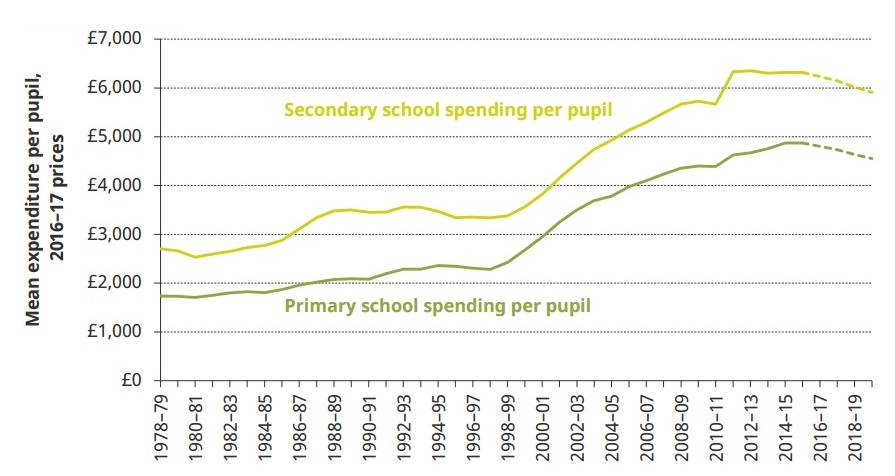

There is little doubt that schools are facing a significant funding challenge. Although, as the IFS points out, this is eased slightly because it follows a “very significant increase during the 2000s”, meaning that school funding is still relatively high in historical terms.

It’s true that the government’s core budget for schools is protected in real terms – and that the overall spend is going up. But that’s not enough to cover rising costs and the increasing number of pupils.

The figures may look decent on a central government spreadsheet, but the reality on the ground is one of historic spending cuts. Under the current spending plans, schools are being made to spend less and less on each pupil.