A day after the budget, and a war of words over the state of the nation’s finances is in full swing. One of the biggest bones of contention is living standards.

The chancellor, George Osborne, says the average household will be around £900 better off in 2015 than in 2010. The Labour leader, Ed Miliband, says: “People are £1,600 a year worse off.”

Who’s right?

The analysis

There appears to be a massive difference between the two sides, but actually both are right – because they are talking about two very different things.

The Labour number works if you only talk about wages, adjusted for inflation. It’s true that pay has been growing more slowly than inflation for years, so real earnings have fallen.

That appears to be changing right now, and Labour’s analysis only takes us up to 2014, while Mr Osborne’s number is a prediction about what will happen this year.

The “£1,600 worse off” claim is a gross figure that ignores the effect of taxes, that fact that the employment rate has risen, and the fact that people don’t just receive income from wages – money also flows in to households from state benefits, pensions and so on.

The “£900 better off” claim, trumpeted by Mr Osborne yesterday, is based on real household disposable income per head – a broader measure of household income.

It’s not perfect, but it tells a similar story to analysis done by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the economics think-tank who effectively adjudicated on this dispute in their post-budget briefing today.

The IFS predicted in a recent paper that average incomes (measured using yet another set of statistics) were back to their 2010-11 levels in 2014/15 and will grow next year.

This sounds much more optimistic than Labour’s line, but it really reflects the fact that different groups have fared very differently over the last five years.

If you are in work, Labour’s point about wages might ring true. But if you are a pensioner, you will certainly not be £1,600 a year worse off than you were in 2010.

The IFS captures this in a graph showing how incomes have changed for people of different ages. The youngest have done worse and the over-60s have seen their incomes rise:

Low bar

The fact that incomes may soon pass 2010 levels sounds like great news. But the fact is that average incomes plummeted after the crash and have recovered more slowly than after any previous recessions since the 1970s.

It’s really a question of emphasis. IFS director Paul Johnson said: “We are for sure much worse off on average than we could reasonably have expected to be back In 2007 or indeed back in 2010.”

“Having household incomes crawl back up above pre-recession levels six or seven years after the recession hit is no cause for celebration.”

Winners and losers

As the IFS paper last month showed, talking about a fictional “average” household covers a multitude of sins. How you have fared since the financial crisis depends on your individual circumstances.

As we have seen, pensioners have done better than young adults. And households with children have done better than those without.

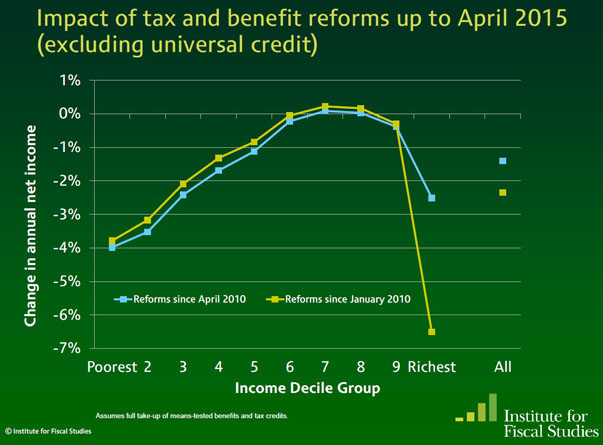

The IFS also thinks that the poorest have seen the biggest fall in their annual income after you add up all the coalition’s tax and benefit policies (that’s the blue line here):

The government disagrees with this. Although the pattern is broadly the same (the richest and poorest hit hardest), it’s the top 10 per cent of earners (“top decile”) who have suffered the most, in the Treasury’s analysis of the changes:

We’ve FactChecked this before and talked about the different methodologies the two organisations use to come up with these two very different stories.

The verdict

Both numbers are basically correct, but the IFS’s independent forecasts of what will happen to household income are much closer to the numbers being used by George Osborne than by Labour.

Of course we have to remember that there is no such thing as the “average household”, and whether you are richer or poorer than in 2010 will depend on your personal circumstances.

The IFS has been saying for some time now that it believes that the lowest earners have lost most as a result of coalition policies, but the government – using a slightly different methodology, disagrees, claiming that the richest 1o per cent have lost the most.

Both agree that middle to higher income earners have been remarkably well protected during five years of austerity.