The NHS has suddenly become one of the key battlegrounds in the Scottish independence debate as the countdown begins to the referendum on 18 September.

The yes campaign says this: “More and more people are waking up to the threat to Scotland’s NHS that a No vote poses. Labour in England say that the English NHS is being broken up, as the UK Government privatises the health service – which would mean automatic cuts for Scotland’s budget.”

Pro-union critics have variously described this line of argument as “desperate”, “scaremongering” and “the biggest lie of the independence campaign”.

We think both sides have made dubious claims about public service spending in recent days. Let’s try to nail some of them.

The analysis

The first thing to remember is that Westminster doesn’t decide how much Alex Salmond gets to spend on healthcare.

The UK Treasury gives a lump sum called a “block grant” to Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. It’s up to the devolved administrations to decide how they spend it.

The grant to Scotland has been cut (slightly) as part of overall austerity programme. So Better Together campaign leader Alistair Darling was wrong when he told the BBC:

“The amount of money that the Scottish government has been getting to spend has been going up all the time.”

“The amount of money that the Scottish government has been getting to spend has been going up all the time.”

While Westminster can trim the block grant it awards to the devolved administrations, if it decides to raise a particular funding stream – like the health service budget – extra money will be passed on to all four nations according to a convention called the Barnett Formula.

The UK government says it has increased spending on the NHS and Mr Darling, a former Labour chancellor, agrees:

“The health budget has increased right through the 13 years of the Labour government, it is (carrying on) increasing and is increasing again.”

“The health budget has increased right through the 13 years of the Labour government, it is (carrying on) increasing and is increasing again.”

But elsewhere, Labour has accused the coalition of cutting spending on the NHS in England.

So has there been a cut or an increase? It all depends on whether you are talking cash terms or real terms.

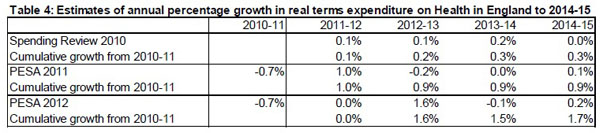

NHS spending in England has always increased in cash terms but when you adjust for inflation it was 0.7 per cent lower in 2011-12 than in 2009-10, according to the UK Statistics Authority:

Note that this real-terms negative growth only happened in one year.

There was cash growth in every year and there has been real-terms growth since 2011/12, with the extra money (“Barnett consequentials”) passed on to Scotland via the Barnett formula.

There’s no dispute about this. The Scottish Government says as much in its latest draft budget:

Note that this paragraph also mentions “the Scottish Government’s commitment to pass on the resource budget consequentials in full to the health budget in Scotland”.

Why did this commitment need to be made? Because Scottish governments have not always spend extra cash arising from increased spending on the NHS in England on healthcare.

This Nuffield Trust-funded study looked at what happened across the UK when the Labour government in Westminster decided to throw more money at the NHS in the 2000s.

Increases on spending in England had to mean more money for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in their block grants.

But the devolved governments did not increase NHS spending as much as England did from 2000/01 to 2012/13.

The authors estimated that Scotland had about £900m to spend on other services by 2012/13 by choosing not to pass on the windfall to the NHS.

All of this suggests that Scotland’s health service has been over-funded rather than under-funded thanks to the Barnett system.

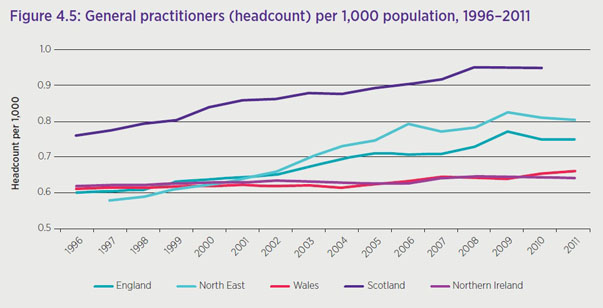

The same report shows that Scotland had significantly more nurses, hospital doctors and GPs per 1,000 population than any other UK country from 1996 to 2011.

It’s no secret that the Barnett formula means that Scotland has enjoyed significantly higher spending on public services in general, including healthcare, than England, for many years.

Last year the Institute for Fiscal Studies calculated that “spending on public services was £7,932 per person in Scotland, 16.6 per cent (£1,128) higher than the £6,803 spent on average across the UK”.

Health spending was around 9 per cent higher in Scotland than the UK average.

“Labour in England say that the English NHS is being broken up, as the UK Government privatises the health service – which would mean automatic cuts for Scotland’s budget.”

“Labour in England say that the English NHS is being broken up, as the UK Government privatises the health service – which would mean automatic cuts for Scotland’s budget.”

There’s no dispute, as this Yes Scotland material claims, that the coalition has introduced more privatisation to the NHS in England, in the sense that more private providers are getting contracts to deliver services.

But the NHS is still funded by public money. And it is the amount of public money spent on healthcare in England that directly impacts on the Scottish government’s finances through the Barnett formula, not the balance of public and private provision: more privatisation in England won’t automatically lead to budget cuts in Scotland.

A number of experts including Oxford politics professor Iain McLean, an expert in the finances of devolution, agree with us on this.

Nationalists tell us that what they mean is the recent reforms in England COULD lead to the wholesale destruction of the NHS as we know it, leading to more patients being charged for care and, presumably, less public funding in the future.

Others, like Labour frontbenchers like the shadow health secretary, Andy Burnham, have made similar predictions. But they remain predictions.

But as things stand now, NHS England can use more private providers, introduce more charges or stand on its head, but there is no pressure on Scotland to follow suit and no reason why health funding to Scotland will be affected.