You wait all day for a government to show up, then two come along at once.

Residents of Aberdeen were left tripping over politicians today as David Cameron and Alex Salmond held rival cabinet meetings within a few miles of each other.

Europe’s offshore oil boom town was the obvious stage for the latest ding-dong in the independence battle.

Mr Cameron wants to convince Scots that only the UK has the economic muscle to get the most out of the UK’s oil and gas reserves.

For Scotland’s first minister, hydrocarbons are the bedrock upon which an independent Scotland’s economic future will be built.

There’s a huge amount at stake. What is Mr Salmond saying about Scotland’s oil wealth?

“Looking at Scotland with oil, we’re among the top 10 countries. We’re eighth in the world of developed countries – the UK would be 18th.”

“Looking at Scotland with oil, we’re among the top 10 countries. We’re eighth in the world of developed countries – the UK would be 18th.”

This is a favourite claim among campaigners who want Scots to vote for independence in the referendum on 18 September this year.

It’s based on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, and assumes that Scotland will get a geographic share of the UK’s oil and gas fields.

This was the top 10 based on 2011 data from OECD countries, according to the Scottish government. Note that most of the world’s wealthiest countries are either geographically small, or have small populations, or both. Bigger isn’t necessarily better.

We think the maths is right, but there are two conceptual problems with trying to claim that Scotland belongs in the top 10.

The yes campaign tends to allocate a geographic share of North Sea oil and gas as though Scotland will automatically assume control of all the hydrocarbons that lie inside Scottish waters, as defined by the “median line” boundary used to demarcate fishing zones.

Most of the experts we have spoken to do think it likely that this is the methodology that would be used to carve up oil and gas, giving Scotland 90-odd per cent of it – but nothing is set in stone.

Like most of the big economic questions including national debt and currency, this would be up for negotiation in the event of a yes vote.

Some economists question the use of GDP per capita as the best indicator of wealth in this scenario. It’s not an unusual measure, but the University of Glasgow’s Centre for Public Policy for Regions argues that it downplays the extent to which North Sea activity is foreign-owned, with the profits flowing overseas.

Gross national income would arguably be a better measure, as it would cover production by businesses actually owned by Scottish citizens – but the figures don’t exist.

“Without oil the productivity, the GDP per head, of the Scottish economy is approximately the same as the UK’s.”

“Without oil the productivity, the GDP per head, of the Scottish economy is approximately the same as the UK’s.”

True. Just because oil is at the centre of the debate today, let’s not assume that Scotland would be lost without it.

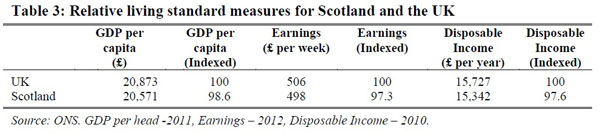

Leave the North Sea out of the equation completely, and Scotland is only very slightly less prosperous than the rest of the UK.

This is true on a number of different measures of wealth, as our University of Glasgow academics have also summarised.

“Recent estimates suggest that activity in the North Sea fields will last for decades with 24 billion barrels of oil equivalent, valued at £1.5 trillion.”

“Recent estimates suggest that activity in the North Sea fields will last for decades with 24 billion barrels of oil equivalent, valued at £1.5 trillion.”

This £1.5 trillion figure has been around for a while and comprehensively attacked by many critics including the Treasury in Westminster.

The nationalists appear to get to that number by multiplying the most optimistic assessment of how many barrels of oil and gas are left in the North Sea – by the price of $100 per barrel. You then convert that into pounds and hope the exchange rate holds up.

In a report last year, the industry group Oil and Gas UK estimated that there are still 15 to 24 billion barrels of oil and gas in the North Sea. Sir Ian Wood’s review of the North Sea industry today takes 12 billion barrels as the likely low extreme and, again, 24 billion barrels as the high.

As far as future oil prices go, anything could happen. The IMF, World Bank, and Economist Intelligence Unit all forecast that prices will fall below $100 a barrel in the long term. Others including the Department of Energy and Climate Change think they will be higher.

Worse, this parliamentary answer from SNP minister Fergus Ewing suggests that both oil and gas reserves have been multiplied by the predicted oil price, whereas natural gas trades at much lower prices.

It also costs money to get the oil out of the sea bed. The UK government claims it would cost more than £1 trillion to extract the fossil fuel reserves claimed by the Scottish government.

Independent estimates of the total cost of future North Sea production are hard to come by, but Sir Ian Wood finds that costs per barrel have gone up five-fold over the last decade.

Efficiency is falling and the industry predicts that it will need substantial investment to get to the harder-to-find remaining reserves.

North Sea production has been falling since 1999 and price shocks mean that the amount of tax revenue the UK government has been able to collect each year has fluctuated wildly.

So that figure of $1.5 trillion certainly doesn’t represent anything like the real future income from the North Sea. The Office for National Statistics says UK oil and gas is worth £120bn, £11bn lower than its previous estimate.

Of course any figure the Scottish government comes up with for the future value of oil and gas will be subject to uncertainty.

If its basic point is that there is a substantial amount of oil and gas left in the North Sea, they are right. Assuming a geographic share, Scotland has by far the biggest oil reserves in the EU.

And uncertainty works both ways. What if oil prices soar for some reason? What if companies keep discovering new oil fields?

Professor Alex Kemp, an academic much quoted by nationalists for his estimates of Scottish waters, sums up the situation like this: “Oil prices have been very volatile and this should remain the case over the next few years.

“There has been dramatic cost escalation in all activities in the UK continental shelf, and a continuation of this will adversely affect taxable income.

“Production has also fallen at a considerably faster pace than forecast only a few years ago and predicting future production is also subject to much uncertainty.

“There are thus substantial downside risks to the projections made as well as some upside potential from still higher oil prices. The former risks are probably the stronger ones.”

“I mean handling the oil and gas resource for the community as a whole as Norway has accumulated much of its revenues for a futures fund for future generations.”

“I mean handling the oil and gas resource for the community as a whole as Norway has accumulated much of its revenues for a futures fund for future generations.”

In the mid-1990s, mindful of see-sawing oil prices, oil-rich Norway started to invest significant amounts of its offshore income into an investment fund, now worth £450bn.

The Scottish government has praised this approach and contrasted it with the British approach of using the revenue to fund general government spending.

Of course, like all savings plans, building up oil wealth for future generations would mean spending less in the short term, which might be painful or impossible.

Economists have cast doubt on an independent Scotland’s ability to start paying into an oil fund without raising taxes or cutting spending, saying the books just don’t balance.

The think tank NIESR put it bluntly in a recent study, saying: “No surplus revenues would be available to fund a Norwegian-style fund.”