The claim

“Our outcome rate – one in three positive – is the same, whether you’re black or white … We find the same rate amongst the people of colour and the people not of colour that we stop.” – Cressida Dick, Metropolitan Police Commissioner, 8 August 2017

The background

The Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Cressida Dick, has defended the force’s stop and search tactics.

The practice has been frequently criticised for disproportionately targeting black people; some have argued it is evidence of institutional racism in the police.

There is no dispute that black Londoners are stopped and searched proportionally more often than white people. But yesterday, the Commissioner claimed this was not due to unfairness.

She said that the higher rates of stops and searches among black people were justified because the proportion of positive outcomes were the same, regardless of ethnicity. In other words, the results prove that the police are not biased.

Dick said: “I think that shows – in terms of our activity – fairness.”

The analysis

Police figures confirm that nearly a third of all stops and searches in London lead to some form of further action (police call this a “positive outcome”).

But 68 per cent of the time, officers decide to take no further action (NFA), which suggests their search found no evidence of any wrongdoing.

However, if we break this down by ethnic appearance, a slightly different picture emerges.

Among white people, 36 per cent of cases result in a positive outcome. But among black people, the figure is lower at just 30 per cent.

This suggests that a higher proportion of black people are needlessly stopped and searched, despite not having done anything wrong.

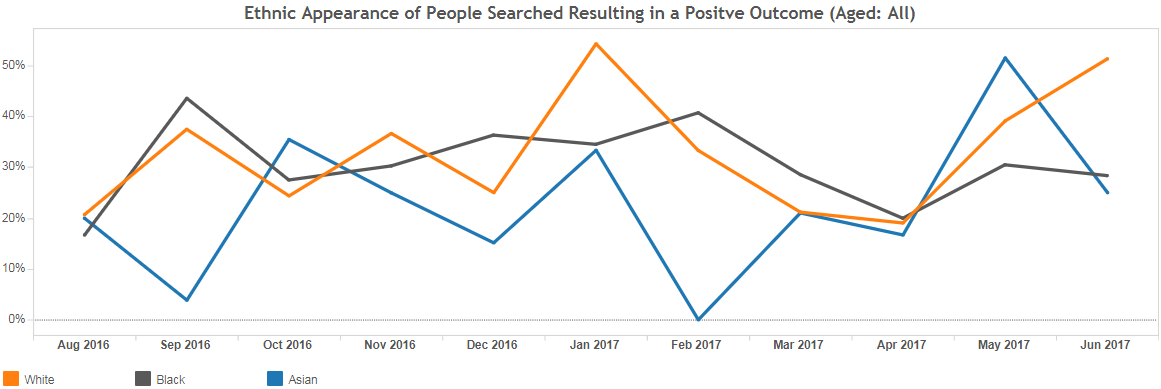

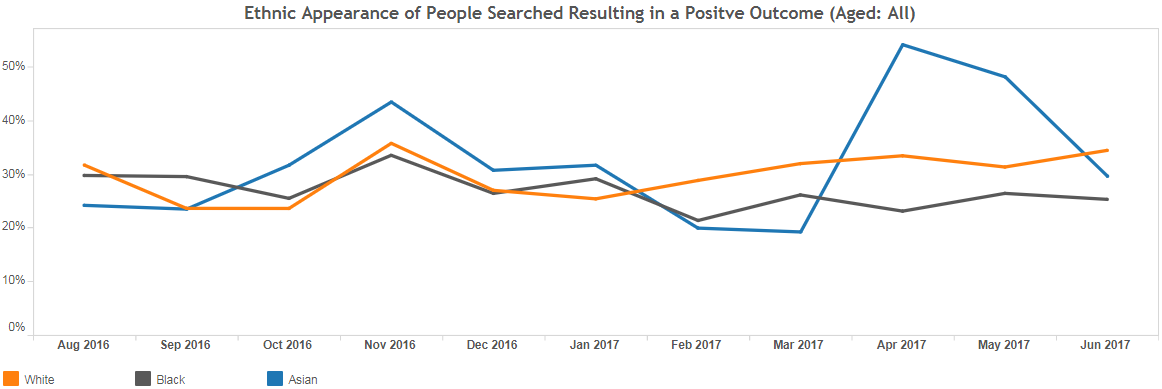

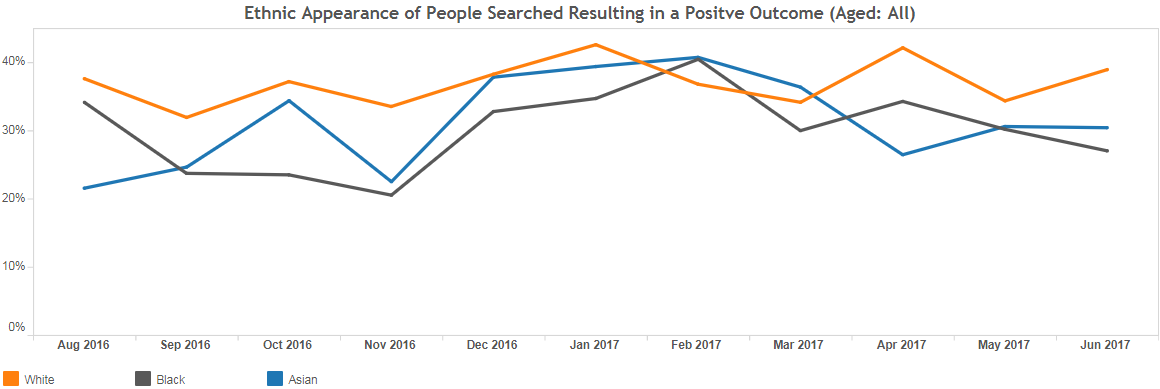

(This is according to the latest figures, but it has fluctuated over time).

But this is just the broad picture. If we look at the specific reasons that police give for conducting a search, there is even more disparity between outcomes.

For instance, half of white people who are stopped on suspicion of having a gun turn out not to have one.

But among Asian people, that figure is far higher – three quarters are let off with no further action.

There are also differences between areas of London.

In Lambeth, which sees the highest volume of stop and searches, further action is brought against more than a third of white people, compared to a quarter of black people.

And in Camden, action is brought against 39 per cent of white people but only 27 per cent of black people.

It’s worth noting, too, that the initial outcome of stops and searches is not an ideal method for measuring the potential for ethnicity bias. After all, even after being stopped, it is possible that police could treat people with different degrees of leniency.

For instance, carrying suspicious items could result in an arrest for “going equipped”, but could equally well be dismissed if police are convinced by the person’s explanation for carrying them. What’s more, even if someone is charged, they may later be found innocent in court.

The verdict

Cressida Dick was broadly correct to say that around a third of all stops and searches result in a so-called “positive outcome”. But there are still differences between ethnicities.

It could perhaps be argued that overall difference is fairly small – six percentage points. But given the sensitivity and importance of this issue, many people will think this difference is worth acknowledging – something that Dick did not do.