Name five towns that have been “swamped” by EU migrants.

That was the challenge from ex-home secretary Jack Straw this week after cabinet minister Michael Fallon used the loaded phrase in a TV interview.

The Conservative defence secretary told Sky News ministers wanted “to see what we can do to prevent whole towns and communities being swamped by huge numbers of migrant workers”.

He added: “In some areas, particularly on the east coast, yes, towns do feel under siege from large numbers of migrant workers and people claiming benefits. It is quite right that we look at that.”

Mr Fallon has since said he was “a bit careless with my words” and the Prime Minister distanced himself from the remarks.

But are some areas of the UK right to feel overwhelmed by immigration from the European Union?

How many Europeans?

According to the Office for National Statistics, 2013 was the first year on record when the immigrant population contained more EU than non-EU citizens.

These are the top ten countries of birth for UK residents born elsewhere in the EU:

http://cf.datawrapper.de/3MS95/1/

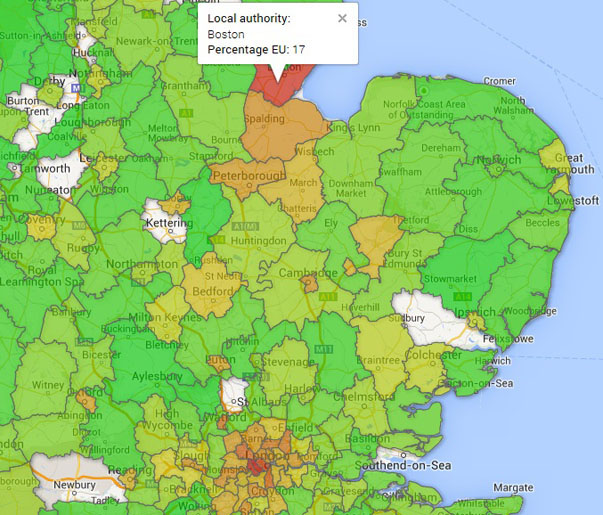

We can also check where people born in the other 27 EU countries were living last year.

In 25 of the 321 areas of England and Wales for which we have data, more than 10 per cent of residents were born in another EU member state.

Some 15 of those were London boroughs. Some notable hotspots outside London were Luton, Peterborough and Boston in Lincolnshire, where 17 per cent of the population were EU migrants.

Do people feel swamped?

Of course we don’t know how the average resident of Boston feels, but it’s not necessarily the case that people in areas of high immigration are the most worried about it.

As we found in a previous FactCheck, data from the British Social Attitudes survey suggests the opposite: Londoners and others more likely to be in regular contact with migrants have the most positive views about immigration.

Benefits

Mr Fallon said: “Towns do feel under siege from large numbers of migrant workers and people claiming benefits.”

But it’s probably wrong to run those two groups together, as though migrant workers are more likely to claim benefits than natives.

The opposite is probably true, according to a growing body of research.

Housing

You might think that house prices and rents would go up in areas of high immigration, but it may not be that simple.

A new paper by an economist from King’s College London suggests that immigration (not just from the EU) actually has a negative effect on local house prices.

Dr Filipa Sa looked at 170 authorities in England and Wales and found that an increase in immigrant population equal to 1 per cent of the local population reduced house prices by 1.7 per cent.

Her explanation is that natives leave the area in roughly equal numbers as migrants move in, so the demand for housing doesn’t increase.

Oxford University’s Migration Observatory says people born abroad are much less likely to be home-owners and are three times as likely to be in the private rental sector, which could push up rents.

Foreign-born individuals are slightly more likely to live in social housing than those born in the UK — 18 per cent compared to 17 per cent.

Various studies reject the popular idea that foreigners get priority on council waiting lists, although migrants may tick more of the boxes that bump you up the list.

Earlier this year, LSE academics found that “the rising number of immigrants and the change in the allocation rules can explain about one-third of the fall in the probability of being in social housing, with two-thirds being the result of the fall in the social housing stock”.

Jobs and wages

Most studies suggest the impact of immigration on employment and wages tends to be surprisingly small.

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research found “no association between migrant inflows and claimant unemployment”.

There was no evidence of natives finding less work thanks to immigration in periods of low growth or during the recent recession.

Some studies have found that increases in the immigrant population lower the average wage very slightly.

Researchers at University College London found the opposite: there was an overall positive impact of migration on wages. But some natives did better than others.

Wages went down for the lowest earners thanks to competition from migrants. But UK-born middle and higher earners found that immigration tended to increase their wages.