The claim

“England and Wales are safer than they have been for decades with crime now at its lowest level since the survey began in 1981.”

Crime prevention minister Norman Baker, 23 January 2014

The background

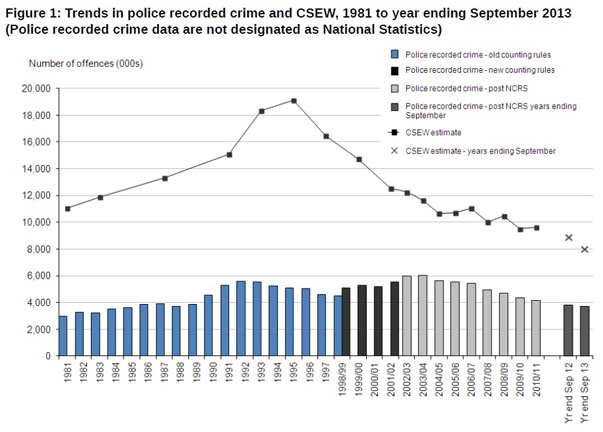

In any other year, this would have been a straight good news story. Police recorded 3.7 million offences in the year to September, a decrease of 3 per cent on the previous year.

The main alternative measure, the Crime Survey for England and Wales, shows an even bigger fall of 10 per cent in crime against households and adults.

But the official crime figures have come under unprecedented attack in recent months, with UK Statistics Authority going so far as to strip the police crime figures of their officially approved status following accusations that officers have been fiddling the numbers.

Crime is said to have fallen dramatically in Britain over the last two decades, but could this all be smoke and mirrors?

The analysis

The accusation that police officers of all ranks routinely fail to record crime accurately is not a new one.

Back in 2009, retired chief inspector-turned-academic Dr Rodger Patrick laid out details of how resourceful bobbies can “game” the numbers.

Arguably the most serious malpractice he described was the technique of “cuffing”, where crimes are made to disappear – as though up the sleeve of a magician – because officers dismiss allegations as false or downgrade the seriousness of an incident.

Evidence from other sources strongly suggests that this still goes on.

An Independent Police Complaints Commission investigation into the Met Police’s specialist rape investigation unit Sapphire found that officers who “felt under pressure to improve performance and meet targets” were encouraging victims to retract allegations so that incidents could be classified wrongly as “no crime”.

In other words, victims of serious crimes were being failed so the unit could improve its sanction-detection rates.

Last year whistleblower PC James Patrick told a parliamentary committee that the Met was routinely downgrading the most serious crimes. Violent incidents that should have been classed as robberies were being recorded as thefts, while cases of rape and sexual assault were being under-recorded.

The head of the Met, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, initially defended his force’s figures, before admitting that PC Patrick’s allegations contain “a truth there that we need to hear”.

An investigation into Kent Police by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary found that the force was under-recording about one in every ten crimes, although the watchdog “found no evidence of this being as a result of deliberate breaches of the rules”.

Tom Winsor, the current chief inspector of constabulary, is carrying out a wider investigation and says he expects to find some evidence of forces fiddling the figures.

Most recently, the UK Statistics Authority removed the National Statistics designation for police-recorded crime stats, saying: “There is accumulating evidence that suggests the underlying data on crimes recorded by the police may not be reliable.”

Are police recorded statistics so unreliable that we ought to doubt whether crime really has fallen over the last two decades?

Criminologists are divided on this, but most point out that the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is compiled without any input from the police but shows the same broad trend of falling crime.

Professor Stephen Shute, chair of the crime statistics advisory committee, told us: “These is good evidence from crime counting across many western countries that crime has been falling throughout the 2000s. It is not just true of England and Wales.

“This has been reflected in BOTH police recorded crime AND the CSEW. So that duplication in trends should give us reassurance that crime is indeed falling.”

Dr Tim Brain, a former chief constable of Gloucestershire, said he doubted that Sir Tom Winsor would find evidence of inaccuracy beyond a few percentage points, not enough to alter “the big picture” of falling crime.

But both men, along with many other academics, warn that the crime survey has serious weaknesses too.

Critics say the questionnaire no longer reflects the changing nature of criminality. Rising levels of cybercrime are not reflected in the survey, while plunging rates of burglary and theft from cars reflect improvements in security devices.

Marian FitzGerald, visiting professor of criminology at the University of Kent, is an outspoken critic of the CSEW, saying the government’s decision to exclude categories of crime like credit card fraud kept the overall crime figure deceptively low.

She has said: “The police service has been driven for nearly 15 years by the imperative to demonstrate year-on-year reductions in crime. So it has developed a mindset which is resistant to recognising new types of crime, such as card fraud and the many scams perpetrated over the internet, and has been more than happy for the Home Office to absolve it of taking any responsibility for them.”

Professor Steve Hall from Teesside University said he mistrusts both set of figures. He told us: “Statistics are always wrong. You’re turning the qualitative, real world into a set of numbers.

“Crime is not falling, it’s mutating. The police have been fiddling the figures for a long time, but this is the police and the government in cahoots. The government want the figures to go down. The police are colluding because they don’t want to look like they are not doing the job properly.”

Richard Garside, director of the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, said it is almost meaningless to talk about the overall crime rate when the figures contain such a huge range of offences that affect different groups of people in different ways.

He pointed us in the direction of this fascinating study which looks at every homicide in Britain between 1981 and 2000.

The headline was that the overall homicide rate went up significantly in those years, but not everyone needed to worry equally. Murder rates only went up among men, and in poor areas.

If you were a woman, or lived in a rich area, your chances of being murdered fell slightly and your perception of crime would, or should, have been very different.

The verdict

Almost no one trusts the statistics recorded by the police, and the most damning accusation is that officers have been failing the victims of serious crimes in order to massage the figures.

Optimists take some solace in the fact that the CSEW is also showing a reduction in many categories of crime.

And some academics point out that there is a smaller fall in the police numbers than in the CSEW, which could be evidence of the recording rate actually rising.

Others question both sets of statistics and think our reliance on numbers and obsession with the headline rate of overall crime are unhelpful.

The one thing almost everyone agrees on is that immediate action is needed to restore public confidence in the official crime figures.