The claim

“Ed Miliband would never clear the overall headline budget deficit. He would run a budget deficit permanently, adding to debt indefinitely, every year, forever.”

“Ed Miliband would never clear the overall headline budget deficit. He would run a budget deficit permanently, adding to debt indefinitely, every year, forever.”

David Cameron, 15 December 2014

The background

David Cameron has said voters face a clear choice between “competence and chaos” as they weigh up Labour and Tory plans to deal with the deficit.

The prime minister said Ed Miliband’s looser spending commitments could add £500bn to the national debt in the long term, which would mean taking “a massive gamble with our future”.

Scaremongering, or a fair assessment of the economic battle-lines?

The analysis

There’s no dispute that Labour’s targets on reducing the deficit and cutting national debt are looser than Conservative plans.

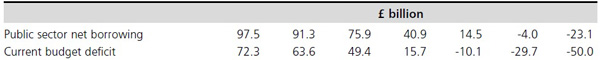

The Conservative chancellor, George Osborne, wants to eliminate the deficit by 2018 and run a surplus of £23bn by 2020.

The price of this is more austerity. In fact public spending will fall to its lowest level as a percentage of GDP since the 1930s, according to the independent Office for Budget Responsibility.

Labour want to eliminate the deficit too, but at an unspecified point in the next parliament, which means a Labour government could balance the books two years later than the Conservatives.

Now here is the tricky bit. When Labour talk about the deficit, they mean the current budget, which covers most day-to-day government spending but excludes capital spending on infrastructure.

The current budget deficit is around £72bn and is forecast to shrink to zero by 2017.

When George Osborne talks about the deficit, he means “headline” public sector net borrowing (PSNB), which includes capital spending. Now the deficit is somewhere around £97.5bn and will not disappear until 2018, assuming tough plans for cuts can really be put in place.

Labour have not included infrastructure spending in their target, which leads us to believe they will spend more on capital than the Conservatives if elected.

On the other hand, Labour frontbenchers have repeatedly said there will be no extra borrowing to fund any spending commitments they make in their manifesto for next year’s election, including infrastructure.

It’s really difficult to know how to reconcile these two things, and Labour have not given us a straightforward answer.

Our best guess is that the party’s election manifesto will indeed be fiscally neutral, in the sense that tax and spending giveaways and takeaways will be exactly balanced.

But the manifesto probably won’t give us exact costings for deficit reduction.

So all this talk about manifesto commitments is arguably a bit of a red herring. All they are saying is that they won’t add to the mountain of debt, not how they intend to reduce it.

Actually it seems to us that it all boils down to a straightforward question for Labour: will the deficit as defined by George Osborne and most economists (including capital spending) fall under a Labour government, or could it go up, thanks to capital spending?

We’ve tried to get a straight answer on this but failed.

If the answer is that the headline deficit could indeed grow, then David Cameron could be right.

Mr Cameron quoted some figures apparently worked out by the Treasury today which suggest debt could increase by £500bn under Labour.

We haven’t been shown the calculations but in principle, if Labour borrowed tens of billions more a year for decades, debt would certainly rise by something like this amount.

So far so good for Mr Cameron, but there are a couple of things we ought to remember.

The Conservatives haven’t spelled out exactly how they are going to achieve their deficit reduction numbers either.

And David Cameron is assuming that Labour will definitely spend tens of billions more than the Tories, when it’s probably fairer to say that Ed Miliband has left himself more room for manoeuvre on spending.

At no point has the Labour leader said that he will “run a budget deficit permanently”. In fact, Labour have made a commitment to get the the national debt falling “as soon as possible” in the next parliament.

The verdict

Despite the complexities and half-truths, there are some clear differences between the parties.

The Conservatives have the toughest spending plans and are the only party committed to running a budget surplus by the end of the next parliament.

The Lib Dems have matched the Conservative commitment to eliminate the deficit by 2018, which is a more challenging target than Labour’s, but they haven’t signed up to more Tory cuts after that.

Instead, the Lib Dems would spend on some big infrastructure projects.

We’re still not clear on Labour’s real position on capital spending, but overall the party has left open the possibility of spending more than either the Conservatives or Lib Dems.

Carl Emmerson from the Institute for Fiscal Studies told us: “All three need to find some fiscal tightening, but the Conservatives would do a lot more. Under the Conservatives you can expect deeper cuts to spending, but in return you get lower borrowing and debt.”