The autumn statement? We’re well into December and it’s brass monkey weather here at FactCheck towers, but let’s not quibble about the name.

The chancellor, George Osborne, gave the nation the kind of upbeat take on the strength of the recovery designed to warm the cockles of the heart.

Labour says ordinary voters are being left out in the cold, and falling living standards mean it doesn’t feel like a recovery to most people.

As ever, the devil was in the detail and FactCheck was on the hunt for half-truths, lies and spin.

“So today we set out in detail the largest package of measures to tackle tax avoidance, tax evasion, fraud and error so far this parliament. Together it will raise over £9bn over the next five years.”

“So today we set out in detail the largest package of measures to tackle tax avoidance, tax evasion, fraud and error so far this parliament. Together it will raise over £9bn over the next five years.”

We’ve got one little problem with this, and one big one.

The forecast of a £9bn windfall for the exchequer includes various measures gathered under two titles: “avoidance, tax planning and fairness” and “fraud, error and debt”.

The total amount of money the government expects to claw back from all these policies does come to just under £9bn, but some of the measures have little to do with clamping down on illegally or morally dubious behaviour.

One change included here is the decision to make foreign investors pay capital gains tax on sales of UK property.

It may or may not be a good policy, but it’s got nothing to do with tax avoidance or evasion. The foreigners who didn’t pay the tax before weren’t breaking the law or doing anything underhand.

In fairness, today’s documents do break down the £9bn headline figure to make it clear that only £6.8bn is expected to come from “tax avoidance and evasion” specifically, and £3.5bn will come from “the richest”, thanks to the closing of various loopholes that let tax planners abuse the rules.

Fair enough. But the official papers also confirm what we found out in October: that an agreement with the tax authorities in Switzerland to get hold of unpaid UK tax stashed secretly in offshore accounts has failed to recoup anything like as much money as we hoped it would.

In autumn last year Mr Osborne thought the Swiss deal would bring as much as £5.3bn to UK government coffers over six years. Now that has been revised down to just £1.9bn.

It’s thought a similar deal in Liechtenstein could outperform expectations.

But we are still likely to be down overall to the tune of several billion pounds, putting today’s announcements on tax evasion in a less flattering context and casting some doubt on predictions of future revenue.

“Real household disposable income is rising.”

“Real household disposable income is rising.”

A difficult one to call, as we have already seen.

Basically, when Labour talks about a “cost of living crisis”, it means inflation is rising faster than wages.

That is true: prices went up faster than wages in almost every month since David Cameron became prime minister in 2010.

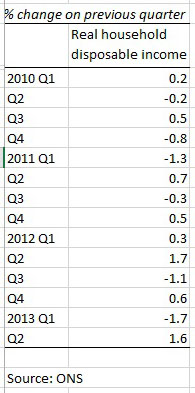

But Mr Osborne doesn’t want to narrow the debate down to wages, rightly or wrongly. He’s using a broader measure – real household disposable income (RHDI) – which includes other streams of income like benefits, interest from savings and share dividend payments.

This measure of income fluctuates pretty wildly, and you can pretty much say what you like about it, depending on when you want to start counting.

RHDI did grow in latest period we know about (the second quarter of 2013), making Mr Osborne arguably right to say that it “is rising” as we speak.

But over the last two quarters we know about, income was down 0.1 per cent.

If you want to compare the latest four quarterd of data with the previous four, there was a fall in household income, making the chancellor wrong. But if you compare the latest full year of results, 2012, with 2011, income is up and he’s right again.

So Mr Osborne isn’t really walking on solid concrete here. Having said that, the figures don’t really support Labour’s assertion that there’s been a collapse of living standards either.

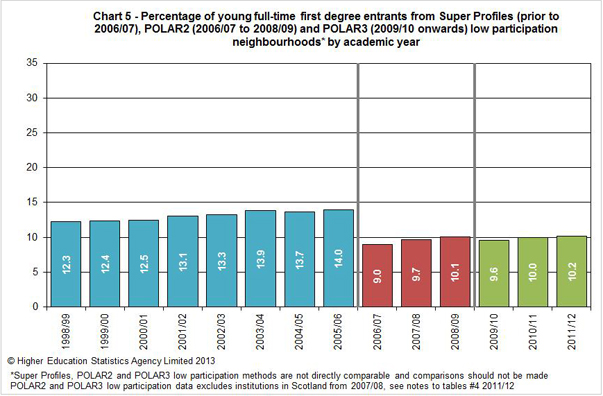

“This year we have the highest proportion of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds applying to university ever.”

“This year we have the highest proportion of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds applying to university ever.”

Technically true, although we shouldn’t crack open the champagne yet.

Data weaknesses mean that “ever” doesn’t mean very much here, and however you look at it, the number of disadvantaged students getting to university is improving at a snail’s pace.

See here for the full story.

By Patrick Worrall