David Lammy, a former Labour minister for higher education, has published data from Freedom of Information requests showing that very low numbers of black students are going to Oxford and Cambridge.

That in itself isn’t news – both the elite universities already publish data on the ethnicity of their students.

But the MP has published figures for individual Oxbridge colleges for the first time – showing how some did not accept a single black undergraduate for several years on the trot 2010 and 2015.

In a Guardian article, Lammy writes: “During this period, an average of 378 black students per year got 3 A grades or better at A-levels.

“With this degree of disproportionately (sic) against black students, it is time to ask the question of whether there is systematic bias.”

Is there evidence of racial bias in the Oxbridge admissions process? Here’s what we know and what we don’t know.

The process

Pupils generally apply to Oxford or Cambridge while they are working towards A-levels or equivalent qualifications.

Admissions tutors at Oxford and Cambridge use grades predicted by teachers as part of the shortlisting process when they decide who to interview.

Candidates who are successful after the interview usually get a “conditional offer” of a place, if they go on to get the predicted grades – usually three As or higher.

Black children under-achieve at school

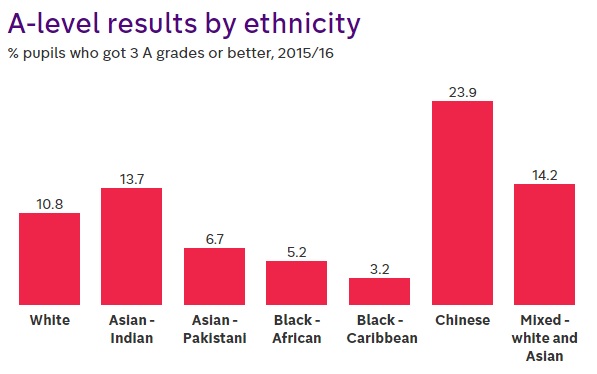

Lammy says just under 400 black pupils get at least three As at A-level a year on average. The first thing to note is that this is a disproportionately low number.

In England, black pupils are significantly less likely to achieve three As than children from other ethnicities, as the latest Department for Education figures show:

Educationalists have been writing about this complex problem for decades and there is a whole literature on the topic.

Numbers of black applicants are low…

Lammy’s figures tell us how many black pupils are getting the kind of grades you usually need to get into Cambridge or Oxford – but not how many actually apply.

The latest figures show that there were low numbers of black applicants to Oxbridge.

… but offer rate is fairly high for SOME black pupils

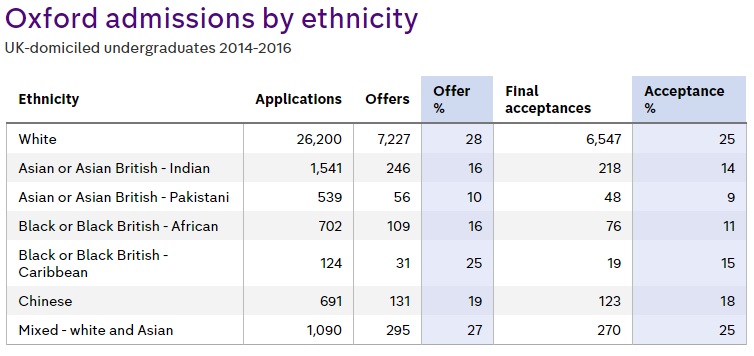

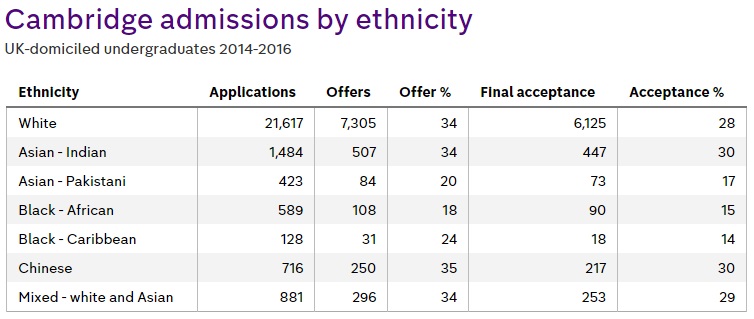

Black students who do apply to Oxbridge are less likely to be offered a place than other races, overall. But there is a big difference between Black people of African and Caribbean background.

A relatively high percentage people who identify as “Black or Black British – Caribbean” are given an offer of a place by the universities, compared to other ethnicities, or even other black people.

At Oxford 25 per cent of these applicants get an offer, compared to 16 per cent for “British or Black British – African” and 28 per cent of whites:

At Cambridge 24 per cent of Black Caribbean pupils get an offer, compared to 18 per cent for Black Africans and 34 per cent for whites.

We ought to say that the sample sizes are very small here. We’re dealing with dozens or hundreds of black people in the various categories, compared to tens of thousands of white applicants.

Few Black Caribbean students who receive offers actually get to Oxbridge

Something happens between these pupils being given an offer, and them actually making it to Oxford or Cambridge.

Both university’s figures show that there is a big drop in numbers at this stage.

At Oxford it’s the biggest percentage-point difference for any ethnic group, although we have to be cautious about reading too much into percentages because of the small sample size.

Why does this happen? Oxford says it could be because the applicant didn’t get the predicted grades, or that they turned down the offer of a place, or decided to go to a different university.

We don’t know which is the biggest factor, as the university does not record this information, but anecdotally, missing grades is likely to be the main reason.

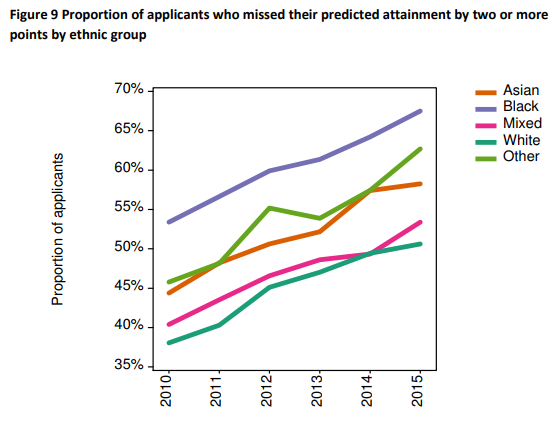

Black students are more likely to miss predicted grades

We do know that black students are considerably more likely than any other ethnic group to miss their predicted A-level grades, according to this Ucas study from last year:

The study doesn’t look at pupils getting three As or more, and it doesn’t break down the “black” category into smaller sub-sets.

So we don’t know if this trend is as marked among pupils with the highest predicted grades. We can’t say for sure if this factor explains the gap between black Caribbean pupils getting an offer and actually reaching Oxford and Cambridge.

The verdict

David Lammy’s figures show that very low numbers of black British students are making it to Oxford and Cambridge, as we have known for some time. Explaining why is the tough part.

On these figures, it’s hard to blame the problem on anti-black bias at the level of the Oxbridge admissions system. (Lammy does not make the accusation of simple racism but uses the phrase “systematic bias”).

The stage of the system where racial bias would show up is the offer rate – that’s the bit the universities have most control over.

In fact, non-white groups do as well as whites at Oxbridge in terms of both offer and acceptance rates.

And both Oxford and Cambridge actually make offers to a fairly high proportion of the small number of candidates who identify as Black Caribbean.

But those candidates are disproportionately unlikely to take up an offer, perhaps because they are more likely to miss their predicted grades.

Overall, black pupils tend to under-perform significantly at A-level, for reasons academics are still arguing about, so the pool of potential candidates for Oxford and Cambridge places is small from the outset.

Lammy has called for the universities to be more pro-active in seeking out talented pupils from under-represented races, regions and economic backgrounds and encouraging them to apply.