The claim

“We’re above 800 million Muslims who are radicalised – more than half the Muslims on earth. That’s not a minority… the myth of the tiny radical Muslim minority is just that: it’s a myth.”

Ben Shapiro

A video by the conservative American political pundit and author Ben Shapiro has attracted hundreds of thousands of internet views.

It was first posted last year but has been shared widely in the wake of the recent attacks in France, thanks to its controversial claim that the majority of the world’s Muslims are “radicalised”.

Is there any truth to this?

The analysis

The idea behind the video is pretty straightforward. Mr Shapiro looks at various opinion polls that have been carried out in Muslim-majority countries in recent years and highlights examples of widespread beliefs that he defines as “radical”.

He then extrapolates from the survey to the whole population of the country. For example he takes a statistic that 10 per cent of 1,000 people in a survey say they want Islamic Sharia law to be the official law of their country.

Ben Shapiro argues that if there are 100 million Muslims in that country that the sample of people in the survey accurately reflects the views of the whole population, so that’s 10 million people he claims are radicalised.

Mr Shapiro repeats this process with a number of Muslim countries and claims to reach a figure of more than 600 million radicalised Muslims.

Then he adds that “it seems fair to assume” that a similar proportion of people in a long list of other largely Muslim countries hold similar views, thus bringing the estimate to more than 800 million people – or more than half the world’s Muslims.

There are a number of issues we can raise with this.

What is a radical?

The video defines people as “radicalised Muslims” if they agree with a number of different views set out in various opinion polls.

These include: believing that “honour killings” of women can be justified; blaming western powers for 9/11; wanting cartoonists who depict the prophet Mohammed to be prosecuted; approving of Hamas; supporting Sharia law; having positive feelings about Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda; tolerating suicide bombings or attacks on civilians.

It’s debatable whether some of these attitudes, though unpalatable, are strictly evidence of a belief in radical Islam. We know, for example, that “honour killings” take place in other cultures, and that 9/11 conspiracism is not a purely Muslim phenomenon.

The reference to the cartoonists come from this 2006 NOP poll for Channel 4, in which 78 per cent of British Muslims thought that the publishers of Danish cartoons of the Islamic Prophet should be prosecuted.

Note that the word was “prosecuted” not beheaded. This appeared to indicate a wider belief among British Muslims that free speech should be curbed if it offends religious groups. Again – controversial, but not necessarily proof of “radicalisation”.

The reference to Hamas comes from the fact that the Palestinian Islamic group enjoys unusually high approval ratings in Jordan, where about half the population is of Palestinian descent.

Whether everyone who approves of the group pushing for Palestinian statehood also signs up to an extreme form of Islam is a moot point. After all, some Christian Palestinians voted for Hamas in the 2006 elections, evidently for political not religious reasons.

Sharia law

It’s perfectly true that some surveys carried out in Muslim countries show widespread support for the implementation of traditional Islamic law or Sharia, although the concept evidently meant different things to people in different countries, and there are huge regional differences.

Mr Shapiro repeatedly quotes polling carried out by the Pew Research Center, a respected US-based think-tank.

Public support for making Sharia the official law of the country varied from 99 per cent of people polled in Afghanistan to 8 per cent in Azerbaijan.

Of those Muslims who backed Sharia, support for extreme punishments like executing those who leave Islam ranged from 76 per cent in South Asia to 13 per cent in southern and eastern Europe.

Of course the Shapiro video only cites Muslim countries with very high support for the introduction of Islamic law, not those where most people oppose it.

On the other hand, while the Pew surveys covered 39 Muslim countries in 38,000 face-to-face interviews, do not include some countries where variations of Sharia are already incorporated into the legal system – notably Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Support for terrorism

A striking number of polls carried out in Muslim countries or immigrant populations after the 9/11 attacks did indeed show that significant minorities were prepared to express support for Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda.

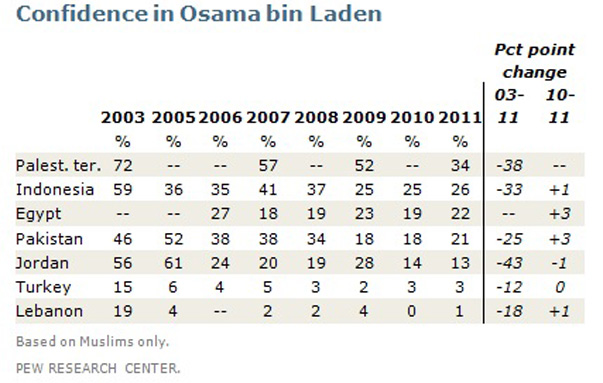

But an overview of Pew polls from 2003 shows how confidence in bin Laden was in decline across the Muslim world before his death in 2012.

And an opinion poll carried out in Egypt, Jordan, Pakistan, Turkey and Lebanon. a year after the al-Qaeda leader’s death showed that generally negative feelings towards the terror network.

In any event, the way people say they feel about bin Laden and terrorism in these polls is often contradicted by their responses to other questions.

A poll carried out in Saudi Arabia in 2007 by the American NGO Terror Free Tomorrow found that 15 per cent of Saudis had a favourable view of Osama bin Laden.

But confusingly, only 4 per cent opposed the view that “the Saudi military should pursue al-Qaeda fighters”.

The group explained this by saying: “For most people, their professed support of terrorism/bin Laden can be more accurately characterized as a kind of ‘protest vote’ against current US foreign policies, not as a deeply held religious conviction or even an inherently anti-American or anti-Western view.”

The same poll found that attitudes to the US and terrorism were not fixed. In fact, the proportion of Saudis who were favourable to the US more than trebled in less than two years. There was evidence of a similarly dramatic change of heart in Indonesia in the mid-200s.

Support for violence

Most Muslims polled by Pew last year said that suicide bombings could “rarely” or “never” be justified against civilian targets “in order to defend Islam from its enemies”.

The detail is pretty interesting. Perhaps not surprisingly given the violent history of the region, Muslims in the Palestinian Territories were most likely to sanction the use of suicide bombings.

Some of the percentages here seem worrying, but of we would want to compare Muslim attitudes to violence to those of non-Muslims to put these beliefs in context.

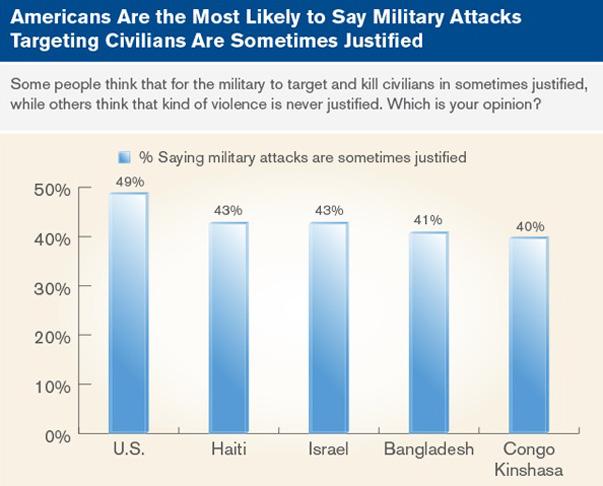

In 2011 pollsters Gallup looked at global attitudes to violence and found that people who lived in Organisation of the Islamic Co-operation member states (that’s most Muslim-majority countries) were less likely than people in non-member states to say that attacks on civilians were sometimes justified.

Who were most likely to say that military attacks against civilians are sometimes justified? That would be residents of the United States, closely followed by Haiti and Israel.

The verdict

The first thing we have to decide is whether we trust surveys of perhaps a few thousand people to represent the views of tens of millions.

Opinion polls can never be completely accurate, though of course journalists, governments and social scientists use them all the time to take the temperature of public opinion.

What Ben Shapiro appears to have done is to take a selection of opinion poll findings that when put together represent a negative view of Muslims.

This is not to gloss over the fact that some polls do show that very illiberal values and concepts can be prevalent in some Muslim countries. Pew surveys show that intolerant attitudes to homosexuality, women’s rights and other religions – among other things – are widespread in some parts of the Islamic world.

They also show that there is a huge diversity of views among different Muslim countries and that people’s beliefs can change dramatically in a few years. A fact that is not seemingly reflected in the Ben Shapiro video.