“The worst of both worlds.” That’s the verdict on the UK university funding system from the Higher Education Commission.

In a report out today, the group of experts points out that students feel like they are paying through the nose after the government allowed universities to charge £9,000 a year for tuition.

But research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) suggests that huge numbers of students will never be able to pay off the government loans they take out to cover the cost of higher eductaion.

The report says: “The government is funding higher education by writing off student debt, as opposed to directly investing in teaching grants. This has created a system where the government is investing, but not getting any credit for it, damaging the perception of the public value associated with higher education.”

FactCheck’s followers have been asking us if the increasing burden of debt means going to university is no longer worth it.

Do the higher earnings graduates are expected to rake in over a lifetime make up for starting their working lives tens of thousands of pounds in the red?

The analysis

The coalition changed the way higher education is funded in 2012. Instead of giving money directly to universities in the form of a teaching grant, the government allowed them to charge students more for tuition.

Many institutions trebled their tuition fees, charging students the maximum of £9,000 a year. Instead of paying the money upfront, students take out a government-backed loan to cover the fees and their living costs.

You start paying the money back once you earn more than £21,000. You pay 9 per cent of earnings above the threshold (which will rise in line with average earnings), at an interest rate of up to 3 per cent above inflation.

If you haven’t paid back the full amount after 30 years, the government writes it off. But what kind of loser will still be paying off their student debt at the age of 51?

Err… about three quarters of graduates (73 per cent) will have some outstanding debt written off after 30 years of work, according to the IFS.

That raises the question of whether it actually pays to get a degree in the first place.

More debt

At first glance, the IFS figures are terrifying. The average graduate will now leave university with £44,035 of debt, compared to £24,754 under the old system.

Only 5 per cent of graduates will have paid back everything they borrowed by the age of 40.

In cash terms the average graduates will have to repay a total of £66,897, as opposed to £32,917 under the old system.

Hang on a minute though. That might seem like a staggering sum, now, but after 30 years of inflation it will look a lot smaller.

If you put the difference in real terms (2014 prices) or net present values (discounting future costs and benefits), and weigh it against a lifetime of probable earnings, it looks a lot less scary.

The IFS thinks the new system will cost just over 2 per cent of lifetime earnings, instead of just over 1 per cent.

How much is a degree worth?

The most detailed recent work on this was carried out for the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills last year by Professor Ian Walker of Lancaster University.

He compared graduates to people who got two or more A-levels but didn’t go to university. There was a massive difference in earning power.

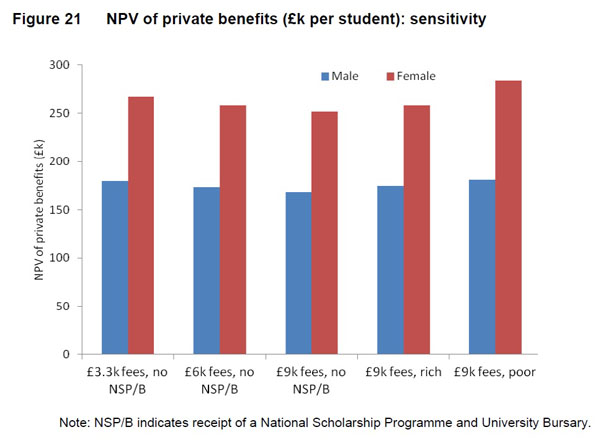

Over a lifetime, a male graduate earned £168,000 and a female graduate £252,000 more than someone with A-levels but no degree.

These sums are net of the cost of student debt with the latest tuition fee levels of £9,000 a year.

In fact, the figures showed that moving to the new funding system made very little difference to lifetime earnings at net present values.

Interestingly, it also didn’t make much difference which university you attended. While you might expect attending Oxford and Cambridge, or another Russell Group university, to come with a big earnings premium, the research doesn’t support this, once you control for confounding factors like student’s family background.

But the class of degree you end up with does make a big difference. Getting a first or a 2:1 adds an average of £76,000 to man’s lifetime earnings and £85,000 to a woman’s, compared to a lower-class degree.

Medicine or Klingon?

While many of us would expect, say, an engineering graduate to earn more than an arts student over a lifetime, the data is apparently pretty fuzzy.

Prof Walker says the literature on which subjects generate the biggest premium is “very thin”, and while there were big differences in his work, it was impossible to isolate the effect of the degree alone.

The problem is that medicine and law courses tend to be more competitive, so you’re already selecting a group of people with above-average abilities. Perhaps they would have earned as much money if they had studied something else.

Prof Walker told us: “Here we found it difficult to convince ourselves that we were estimating causal effects rather than just correlations.”

Of course this doesn’t mean medicine isn’t a good choice of degree, just that it’s difficult to isolate the effect of degree subject from other factors.

The Complete University Guide website offers a list of starting salaries by subject, from dentistry (£33,711) to Celtic studies (£19, 427 – presumably that’s the language, not the football club).

It finds the average graduate starting salary fell by 11 per cent in real terms between 2007 and 2011.

Law of averages

Dwelling on those headline figures of a £168,000 or £252,000 graduate premium doesn’t tell us the whole story about what happens to most people.

Dr Malcolm Brynin from the University of Essex makes the point in this 2012 paper, saying: “There is little point in showing that on average graduates earn more than non-graduates if the pay of the two groups nevertheless overlaps considerably.”

He uses this graph to show the size of the overlap. The modal average pay for graduates (the solid line) is higher than people who just have A-levels (the broken line), as shown by the two peaks of the curves.

“But a high proportion of graduates earns much the same as A-level school-leavers, so that many graduates benefit little from their degrees. Getting a degree is a gamble.”

And it may be that the risk of failing to get a decent financial return from a degree is getting worse. Comparing 1997 to 2008, Dr Brynin found that there were more graduates earning below-average wages. And the proportion of graduates in the above-average pay band fell from about 65 per cent to 52 per cent.

The verdict

So what have we learned? None of the research we’ve found purports to be perfect, but it does suggest a few things are likely to be true:

On average, it’s still worth going to university. The average graduate is still likely to earn considerably more over a lifetime than someone who doesn’t go on to higher education.

But no real person is average, and there is always a risk involved.

You could finish your degree, only to end up earning the same or less than someone else who isn’t a graduate, and isn’t saddled by all that debt.

Lots of graduates and non-graduates earn about the same, and it could be that the risk of under-achieving financially has risen in recent decades.

Not surprisingly, doctors and dentists earn more than others at the beginning of their careers than most arts graduates. But there isn’t a lot of hard evidence to say definitively which degree generates the most earnings over a lifetime.

There’s no need to slash your wrists if you don’t get that place at Oxford, it would seem. Choice of university is relatively unimportant when it comes to earning power.

There is evidence, though, that the class of degree you get makes a big difference to earnings. So if you do decide to go to university, do some work.