Politicians and journalists have spent the last few weeks discussing – and trying to explain – the current crisis in the NHS.

Last week, FactCheck found that since 2010, the number of people waiting more than four hours for treatment in A&E has risen by nearly 600 per cent.

We looked at whether lack of funding and staff shortages might be exacerbating the problem.

But there’s one question that online readers have asked us more than any other: could this be about immigration?

FactCheck takes a look.

What are we measuring?

We’re looking at a key NHS target: the percentage of patients admitted to hospital, transferred or discharged within four hours of arriving at accident and emergency departments.

The most recent monthly data covers November 2017, and is broken down by “Sustainability and Transformation Plan” (STP) area.

In plain English, that means we’re looking at regions like “Coventry and Warwickshire”, “North West London”, “Greater Manchester”, etc. These are geographically bigger than NHS Trusts or Care Commissioning Groups. On average, each STP area covers about 1.2 million people.

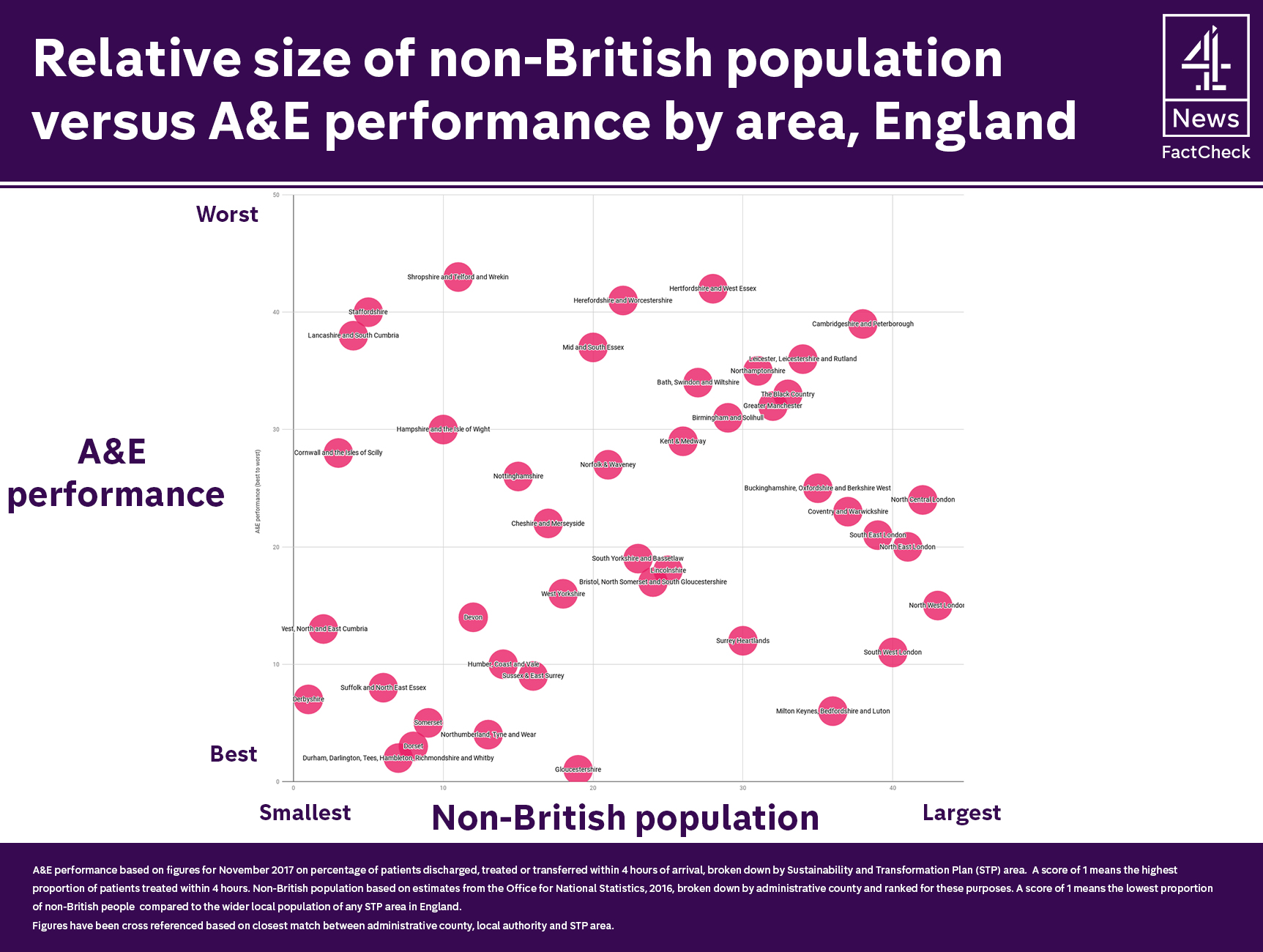

We’ll be comparing A&E waiting time performance with the proportion of non-British residents in each region. That is based on Local Migration Indicators for 2016, which are published by the Office for National Statistics.

The ONS data isn’t broken down by the same geographical boundaries as the NHS waiting times information. We’ve matched up those two statistics in our own analysis – this is our best estimate.

What have we found?

There are certainly areas with relatively high immigrant populations that also perform badly on A&E waiting times.

For example, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough ranks 39th out of 43 for A&E performance. It also has one of the highest proportions of non-Brits living in the area (by our calculations, about 11 per cent of the population is not British).

Areas like Northamptonshire and the Black Country have similar stories.

There are also examples of areas with very few non-Brits doing well when it comes to A&E waiting times. For instance, Dorset ranks third best in England for A&E visits and has the eighth smallest number of foreigners as a proportion of its population.

But there’s equally compelling data that tells exactly the opposite story.

For example, about 31 per cent of people in North West London are not from the UK. That’s the highest rate of non-Brits of anywhere in England. But local A&E departments do pretty well – ranking 15th out of 43.

The region covering Milton Keynes, Bedfordshire and Luton has one of the largest immigrant communities in England (we estimate about 13 per cent of the general population is not British), but ranks sixth best in terms of A&E performance.

And at the other end of the scale, there are plenty of regions (Lancashire and South Cumbria, Staffordshire, and Shropshire for example) that rank low in terms of immigrant populations but where A&E departments are doing badly compared to others.

In other words, there’s no correlation between the proportion of immigrants in an area and the performance of local A&E departments.

The big picture: what do migrants cost the NHS overall?

It seems obvious that if more migrants arrive in Britain and access health services, the cost of running the NHS will go up. But the research into the overall costs and benefits is “tentative”, according to the Kings Fund health watchdog.

We’re often asked about the effects of so-called “health tourism”. That’s where people come to Britain specifically to use health services that they wouldn’t otherwise be entitled to.

The Kings Fund estimates that health tourism costs the UK between “£60 million and £80 million per year. This compares to the annual NHS budget of £113 billion.”

So much for “health tourism” – it costs less than a tenth of one per cent of the total NHS budget. What about the general cost to the NHS of all migrants living in the UK?

This research from the Nuffield Trust points out that the additional cost pressures on the NHS are largely driven by reasons other than migration – namely, our ageing population and the rising cost of wages.

Of course there is another side to the story too: migrants contribute to the economy through tax revenue and GDP growth, so we have to set the costs to the NHS against the economic benefits of immigration.

There is a body of research that suggests international immigrants are less likely to access health services than the native-born, on average, probably because they tend to be younger.

This so-called “healthy migrant” effect is partly why studies like this find that some groups of newcomers (immigrants from the European Economic Area, but not from the rest of the world) have made a positive fiscal contribution to the UK overall.