When a former Russian spy and his daughter were found slumped on a park bench in Salisbury, it wasn’t long before investigators started looking at the Kremlin with suspicion.

The pair were identified as Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia. The British government said they had been poisoned with a military grade nerve agent called Novichok, originally developed in Russia.

Over the following weeks, as the victims remained in hospital, Britain’s relationship with Russia began to fall apart. Diplomats from both countries have now been expelled and all planned high-level contact is suspended.

The stakes could not be higher. With Russia denying any involvement in the attack, the stability of global politics hangs in the balance.

But how strong is the UK’s evidence against Russia? And what do the experts think?

The mysterious newcomer

Secrets about Novichoks were first made public in 1991, when a Russian chemist named Vil Mirzayanov claimed his country had been producing and stockpiling them for years. First in newspaper articles and later in a book, he laid out detailed allegations.

A New York Times reporter who interviewed him in the ‘90s wrote that the nerve agents were “not developed in large quantities” by Russia – but it might still be enough to kill “several hundred thousand people”.

Mirzayanov went on to provide diagrams, purportedly showing Novichok chemical structures, in his book, State Secrets.

“The word ‘Novichok’ translates as ‘newcomer’,” he wrote, adding that their toxicity “was up to 5-8 times higher” than some other nerve agents. And they could be made by combining chemicals which might have legitimate purposes, avoiding the suspicion of weapons inspectors.

On one occasion, a young scientist working on the programme was apparently exposed to the substance and eventually killed. “Circles appeared before my eyes: red and orange,” he told the Novoye Vremya newspaper before his death. “I sat down on a chair and told the guys: ‘It’s got me’.”

The former chemical weapons inspector, Jerry Smith, told FactCheck that Russia ended up being “caught in a Catch-22 situation” over Mirzayanov’s claims about the Novichoks. They arrested him for releasing state secrets, but then denied the nerve agent had ever been produced.

This line has continued ever since: “I want to state with all possible certainty that the Soviet Union or Russia had no programmes to develop a toxic agent called Novichok,” the country’s deputy foreign minister said after the attack in Salisbury.

To this day also, Mirzayanov’s writing still provides the main foundation of what is publicly known about Novichoks. And there is very little else. Most evidence derives not only from limited sources, but also a limited period in history.

As a result, many academics approach the subject with a degree of caution. “You just have to take a reality check and examine whether anything [Mirzayanov] is saying is subject to spin,” explains chemical weapons expert Dr Richard Guthrie.

However, since the attack in Salisbury, there have been questions on social media about whether Novichoks exist at all, or have ever been produced.

This theory has been compounded by a 2011 report from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which noted: “There has been no confirmation of [Mirzayanov’s] claims, nor has any peer review been undertaken in regard to the information on these chemicals in the scientific literature on this subject.”

Another report, published by the Royal Society of Chemistry in 2016, said there had been “no independent confirmation of the structures or the properties of such compounds has been published”.

This is true. But that doesn’t mean Novichoks don’t exist – either in theory or practice. Indeed, all the experts we spoke to agreed there is sufficient evidence to suggest they do exist.

The ambiguity over Novichoks arises because this is not a black-and-white issue. The science and evidence are both nuanced, so questions about their existence require more than a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

Central to this is the fact that Novichoks are a broad class of nerve agent, rather than specific chemical compounds. This makes it distinct from substances like Sarin or VX, which can be precisely categorised and labelled.

“Novichoks are usually made by reacting two molecules which are not on the Chemical Weapons Convention list,” said Dr Peter Cragg, a supramolecular chemist at Brighton University whose research includes work on chemical warfare agents.

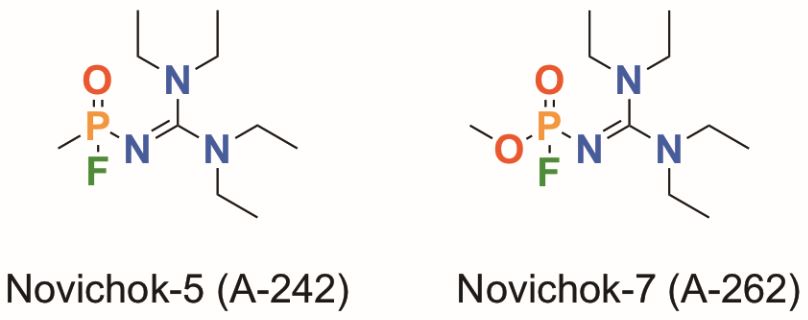

“I have seen over 25 chemical structures claiming to be Novichoks, but whether or not they have all actually been made cannot be verified.”

Professor Andrea Sella, a synthetic inorganic chemist at UCL, told FactCheck: “They’re structures I’ve seen discussed, both in the chemical literature and elsewhere. They are very similar to the ‘classic’ nerve agents Sarin and VX, but they differ in having a side-group with one or two nitrogens linked together by a carbon chain.

“So the Novichoks are that kind of broad class, in which the precise details of the structure side-group determines the properties of the compound.”

One reason why precise definitions can sometimes be tricky in chemistry is that molecules may exist in two asymmetric forms, known as chirality. One example of this is the drug Methadone, according to Alastair Hay, Professor Emeritus of Environmental Toxicology at the University of Leeds.

“Only one part works,” he says, “50 per cent of the mixture is inactive. So when you can’t specifically define these things, you have a bit of a problem.”

The upshot of the ambiguity is that there’s never been a universally recognised definition of Novichoks. Experts disagree about exactly which molecular structures should classify, and there have been no peer-reviewed scientific studies.

There’s also a lack of evidence about which ones are effective, and which are not. Plus, no government has ever offered up information about them, nor admitted making them.

This has made it impossible for regulators like the OPCW to pinpoint exactly what is meant by “Novichok”, and list its molecular structures on the schedule of chemical weapons.

Instead, Professor Hay explained that the OPCW relies on its General Purpose Criteria to rule against them. This says that any chemical used to deliberately harm people can be classed as a chemical weapon.

“The OPCW is not the world police,” Jerry Smith explains. “All they can do is deal with what member states give them… The Russians never offered any details [of Novichoks] to the OPCW, as far as I’m aware. So, with that in mind, they can’t make any comment.”

There is no doubt that defining Novichoks is problematic. Indeed, scientists studying the specific molecules used in the Salisbury attack might potentially have disagreements about whether it can be classified as such.

But, with regards to the broader class of compounds, experts agree that they may well have been developed.

Unique to Russia?

Although Russia developed them originally, it’s likely that several countries have also made small samples of Novichok – or at least know how to.

But because they have avoided being specifically classified by the Chemical Weapons Convention, any countries that have produced them may be able to avoid declaring it.

“I can’t believe that Russia has the sole technology to manufacture Novichoks,” says Jerry Smith. “If you want to make sure you’re protected against an agent which has been spoken about – and, in fact, even their chemical structures are on the internet – one would imagine that’s probably a duty of care.”

As well as the details published by Mirzayanov, there have also been suggestions that Western powers may have learned more when the US helped clean up a former chemical plant in Uzbekistan in the 1990s.

“Apparently – I don’t know for sure – Novichoks were supposedly tested at this particular site,” says Professor Hay.

Dr Guthrie adds: “Nobody has ever given a clear acknowledgement about what information was gathered at the plant. But it’s quite clear, when you chat to those people, that a lot of information was gained by clearing the site.”

It also seems reasonable to assume that secret services have tried to keep an eye on Russia’s chemical weapons activity over the decades – especially in the years after the Cold War. And, if Mirzayanov is to be believed, this might have been particularly easy thanks to lax security.

In 1995, he warned that Russian officials familiar with the chemical weapons programme were being laid off and were desperate for money. The New York Times reported that the production of new weapons had halted, but said Mirzayanov was worried that existing stockpiles might be stolen or transferred.

So the secrets behind Novichoks may not have been very well guarded. And – when combined with the details published in Mirzayanov’s book – it is perfectly possible that other countries had strong intelligence about what Russia was doing.

Based on the chemistry alone, Professor Hay believes that Novichoks could “probably” have been developed by countries other than just Russia.

“A good synthetic chemist could do this work,” he said. “Look at the structures. It would take time and it requires talent, but there are lots of very competent and good synthetic chemists around.”

“There is no chemical synthesis that you cannot imagine someone with a chemical training not being able to do,” Professor Sella added. “Now that the structures are out there, chemists will sit there and speculate ‘how could I make this thing?’.”

Given that other countries might have “potentially” developed Novichoks, authorities investigating the Skripal case will want to rule out the possibility that another country was responsible, said Dr Guthrie.

“If you were a troublemaker wanting to give it in the neck for Russia, this would be something to do, because people’s assumptions would be that it is Russia.”

Meanwhile, Dr Cragg remains slightly more doubtful about the possibility. “We don’t know if other countries have prepared Novichoks,” he said. “They may have done so in order to test antidotes in animal studies or investigated ways to decompose the compounds. But I would be surprised if they have.”

UPDATE (3 April, 2018): In an interview, the head of Britain’s Porton Down laboratory has said its scientists have not been able to prove that the Novichok used to poison Skripal was made in Russia.

“We were able to identify it as novichok, to identify that it was military-grade nerve agent,” he said. “We have not identified the precise source, but we have provided the scientific info to government who have then used a number of other sources to piece together the conclusions you have come to.”

Gary Aitkenhead said that identifying the source would require “other inputs”. He explained: “It is our job to provide the scientific evidence of what this particular nerve agent is, we identified that it is from this particular family and that it is a military grade, but it is not our job to say where it was manufactured.”

Porton Down

Here in the UK, the government has never admitted to having Novichoks of its own. In a statement following the attack in Salisbury, the chief executive of Porton Down said there is “no way” the substance could be linked to it.

He later added: “There is no way anything like that could have come from us or left the four walls of our facility.”

None of the experts we contacted were able to speak definitively about Porton Down’s work in this field, but many believe it is likely the substance has indeed be investigated in the past.

They suggested it’s very possible that Porton Down has held samples of Novichoks – or at least has details about their chemical structures.

“I suspect the British government and Porton knew much more about Novichoks than before it was made public in Russia in the early 1990s,” Professor Hay told us. “It’s the job of intelligence services to get this information.

“I would have thought that what would have happened is that chemists there would look at the structures and set about making them – tiny quantities, that’s all you would need – and then characterise them and put the information in a chemical database for future reference.”

Dr Gurthie added: “If you’re a laboratory – whether that’s in the UK, the Netherlands or Switzerland – and you’re seeing hints of what the structures of these things are, you think ‘well let’s make a quick sample of this and see if our detectors pick it up’. That’s going to be your natural reaction.”

Lab facilities

“To make this, you need the chemical knowledge, the ingredients and the facilities,” says Jerry Smith.

“Those three things have got to hit a sweet spot, in a classic Venn diagram. And that sweet spot is probably very small… You also have to make sure you don’t kill yourself in the process.”

Dr Cragg said: “You would absolutely require a high-tech lab to prepare the binary agents. They are likely to need specialist equipment such as fume hoods and inert atmosphere facilities so the highly toxic agents could be manipulated without being released into the open lab.”

This enormous risk factor is probably the single biggest indication that the Salisbury nerve agent was produced at an advanced chemical lab, rather than being knocked up in a back room nearby. That means, if a foreign country is responsible, it was almost certainly smuggled into the UK.

“I would struggle to see a situation where Russia produced Novichoks in Britain,” says Smith.

Professor Sella explains: “There is no chemistry that one cannot conceive of doing in a back room, if you have the right sort of kit.” But he adds: “I honestly think the risks are just too high to do this somewhere in a back yard or a shed. The toxicity levels are extreme.”

Chemical ID

Regardless of whether Porton has studied Novichoks in the past, it’s a misconception to believe the nerve agent used in Salisbury could only have been identified by comparing it to existing samples.

Scientists say that having a sample might certainly speed up the identification process, but it’s by no means essential.

“The classic way to do it would be to scrape this stuff off whatever surface you found it on. You dissolve it in a solvent and then one of the key things in the first instance would be to conduct a mass spectrometry,” says Professor Sella.

“You determine the mass of the molecule itself – and you can do that with extreme accuracy – which allows you to identify how many carbon [atoms], hydrogens, nitrogens, and so on, are in there.”

“On top of that, when you throw these things through a mass spectrometer, the molecules break down into fragments, so there’s a kind of decomposition,” Sella adds. “That’s very, very useful… That fragmentation pattern turns out to be crucial in being able to fingerprint and work back to what the compound actually is.”

Professor Hay adds: “Chemists are used to defining structures – otherwise how would you have new chemicals and be able to say what they are? But that takes more time and you have to look at many types of procedures to define the structure of something. So the easiest process is to be able to compare it with something you’ve already worked on.”

Jerry Smith says he has “absolutely no doubt” that Porton Down would be capable of identifying Novichok without existing samples. “Bear in mind also that Vil Mirzayanov did actually release some of the Novichok chemical structures, so they’ll be able to look at them for starters. They’ll be able to say ‘yes, this seems to fit in broadly with what the complex idea of a Novichok is’.”

The case against Russia

Even if Russia is not alone in having Novichoks, chemistry can still be used to help point the finger. A clue to this might be found in the government’s description of what they found in Salisbury: “A military-grade nerve agent of a type developed by Russia.”

Chemical analysis can reveal not only what the nerve agent is, but also the particular process used to make it. So, if the UK believes that Russia produces Novichok in a unique way, that may prove to be vital evidence.

“If you’ve got an environmental sample, you would have your nerve agent there, but you would also have some probably unreacted precursor chemicals,” explains Professor Hay. “You would probably have traces of solvent that were used…”

“These can all help to give you a clue as to how something was made. You may also have – within your intelligence information – details of how particular places make these things. So that’s the sort of comparison you’re then in a position to make.”

Hay adds: “On occasions when I’ve been privy to some intelligence stuff, it’s just amazing how much more there is than is in the public domain.”

The government’s case against Russia is multi-faceted; chemistry is only one part.

Authorities will have also considered a wide range of other intelligence sources. Who was in Salisbury on the day? What does the CCTV show? Who were Skripal’s enemies? And what information have the secret services managed to obtain?

At the moment, we simply do not know the extent or strength of the evidence. But this information may potentially be enough to incriminate Russia, regardless of the Novichok chemistry.

In statements on the affair, Theresa May has also factored in Russia’s “record of conducting state sponsored assassinations – including against former intelligence officers”.

Among the high profile deaths which have been linked to the Kremlin are former FSB agent Alexander Litvinenko and Putin critic Boris Berezovsky. So the Salisbury attack fits a pattern.

The motives for Russia (either Putin or his associates) also seem clear: Sergei Skripal was accused of passing information to the UK’s secret services about the identities of Russian agents operating in Europe. So not only was he considered a traitor, his work for the UK may have potentially put the lives of Russian spies at risk.

But investigators will also want to rule out other possibilities, no matter how unlikely they may be. Crucially, whether another state actor could have tried to frame Russia – perhaps to undermine its credibility on the world stage. Some people have also questioned whether there could have been a security breach at nearby Porton Down, including theft by a foreign government.

Meanwhile, there have been questions raised about the apparent vagueness of some of the UK’s allegations. For instance, one statement claimed: “We have information indicating that within the last decade, Russia has investigated ways of delivering nerve agents likely for assassination.”

Does “within the last decade” mean “continually throughout the last decade”, or simply “once at some point in the last decade”?

FactCheck asked the Foreign Office what was meant, but we have not received any clarification. We will update this blog if we do, but it’s very possible that the vagueness is deliberate so as not to show Russia all the cards.

The verdict

Allegations over chemical and biological weapons have a troubling history. Both accuser and accused have misled in the past.

In the ‘80s, for instance, President Reagan’s administration repeatedly accused the Soviet Union of supplying Vietnam with a biological weapon called Yellow Rain. But the scientific analysis proved to be staggeringly wrong: the mysterious substance was, in fact, just bee excrement.

And, of course, the intelligence about Iraq having weapons of mass destruction in 2003 also turned out to be wrong.

So, with the Salisbury incident, investigators will need to ensure the evidence is watertight.

“For me, it’s a combination of what this thing was, plus circumstantial stuff,” says Professor Sella.

“I think, on the basis of the chemistry, the evidence against Russia is very strong,” adds Dr Guthrie. “I would categorise it as strong evidence, but not proof at this point.

“But, take into account what happened with Litvinenko…”