Farewell GCSEs, welcome baccalaureates

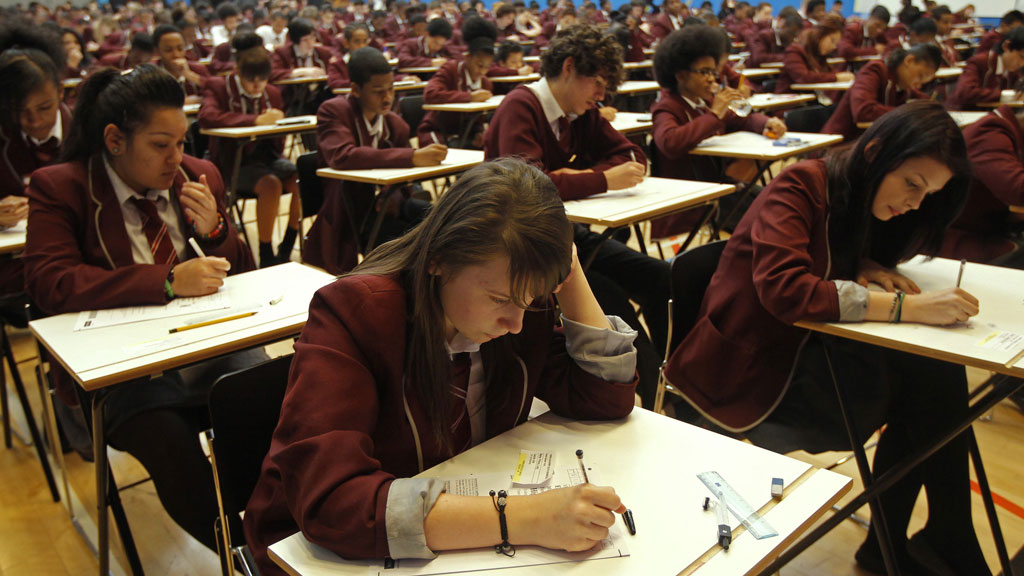

As the government announces plans to replace GCSEs with a tougher, O-level style qualification in England, Channel 4 News looks at the advantages and disadvantages.

GCSEs were introduced in the late-1980s by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government amid concern that the two-tier system of O-levels and CSEs was branding children as successes or failures at the age of 16.

The most able sat O-levels, while the less academically gifted were entered for CSEs.

While a top grade at CSE was technically equivalent to a C at O-level, it was not always viewed in this light, particularly by employers.

Back then, it was argued by many that having two types of exam was reminiscent ot the post-war grammar/secondary modern split (again, creating successes and failures) that was replaced by comprehensives in the 1970s.

Former chief inspector of schools, Sir Mike Tomlinson, who is “positive” about the changes, told the BBC: “As a teacher, I remember that system well… terribly difficult decisions had to be made as to whether you entered a student.”

Improved results

The GCSE was brought in to rectify this problem, and since its introduction results have improved dramatically, with far more A grades than there used to be. The problem is that there are question marks over the validity of these results.

Critics say GCSEs have become too easy to pass or excel in and do not accurately reflect what pupils have achieved, while defenders argue that teaching has improved and pupils are simply better at passing exams. The government says it is addressing this issue.

With GCSEs, courses are “modular”: learning is broken up into units and pupils are assessed over two years.

“Modular” courses will now come to an end, to be replaced by a single, three-hour exam – the way pupils were tested when O-levels were in place.

There will be fewer top grades and just one exam board for each subject, to resolve the current argument that the rigour of a GCSE varies according to who is marking it.

At the moment, the accusation is that some boards’ exams are easier to pass than others’, as they compete for business from schools.

There were suggestions during the summer that GCSEs would be replaced by two types of exam – O-levels and CSEs mark two?

The English baccalaureate - the key questions and answers. Read Gary Gibbon's blog.

One exam for all

But the Conservatives’ Liberal Democrat coalition partners argued against this, and a compromise was reached whereby all children will sit the same exams, English baccalaureate certificates (EBaccs).

Deputy Prime Minister and Lib Dem leader, Nick Clegg, said the reforms would “raise standards for all our children” but would not “exclude any children”.

But how can a tougher exam, taken by all pupils, not exclude some of them?

Sally Coates, principal of Burlington Danes Academy in west London, agrees this will be difficult, but said: “Good schools will enable all children to pass this qualification.”

Education Secretary Michael Gove has said that exams could be taken at 16, 17 or 18, which would mean that everyone would not have to achieve the same standard at the same time.

One criticism of GCSEs is that anything below a C grade has come to be seen as a fail, with grades A-C used to formulate school league tables. The government has its work cut out if it wants to change perceptions.

Mark of excellence

The reforms are designed to give an accurate reflection of children’s achievements, with parents, universities and employers confident that an A grade on an application form or CV is a genuine mark of excellence.

In future, far fewer pupils will receive top marks, and starred As, which were introduced because so many children were being awarded As, will be scrapped.

Pupils can currently resit modules if they fail them, but when the changes are introduced, they will only be examined once and will have to resit the whole exam, rather than a part of it.

There will also be more essay writing, a staple of the old O-level. Ms Coates said: “In some areas the GCSEs have been too easy. There’s been a shortage of essay-type answers in exams and more short responses.”

“Modular” courses were introduced because it was felt that continuous assessment was better than two years of work being scrutinised in a single exam.

Brutal

One of the problems with the new system is that although we will be returning to an era when the validity of results was not widely questioned, a three-hour exam is a brutal way of testing two years of study.

For entrants, slipping up on the day can have dire consequences, even if they are capable and have worked hard.

We are also going back to a time when the number of A, B and C grades was limited, regardless of whether standards had improved across the board.

Then there is the issue of whether, with most pupils in education or training until 18, there is any need tor national exams at 16.

Lord Kenneth Baker, who as education secretary was one of the architects of the GCSE, believes it would be better for children to be tested at 14.

Martin Johnson, deputy general secretary of the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, agrees that 16 is no longer the right age for crucial exams.

“Since young people will have to stay in education and training until they are 18, there is growing opinion that we no longer need external testing of 16-year-olds,” he said.