Haiti’s forgotten rape victims

Exclusive: Hundreds of girls and women have been raped in Haiti’s makeshift refugee camps and, as Channel 4 News reporter Inigo Gilmore reveals, their attackers are rarely punished.

Warning: You may find some of the detail in this report distressing.

For 18-year-old Choucoune the birth of her first child should have been a joyous time, but the father of her seven month old baby is the man who raped her.

“People tell me I should show her affection but I just feel sad. They told me I should get rid of her but it was too late by then. When I see the child I just see her suffering in my hands…” Choucoune told me.

Choucoune fled to a camp on the fringes of Port au Prince, but even here she doesn’t feel safe.

She told Channel 4 News: “I’m alone in the house here with the child. I dont feel safe. I end up spending my day with my brother. But I cannot sleep here at night. I go to stay with another woman,” Choucoune said.

There are many like Choucoune – women who survived Haiti’s earthquake more than a year ago, only to have suffered further trauma in the displacement camps set up after the disaster.

According to Amnesty International, women and girls living in these camps are increasingly at risk of rape. The numbers are difficult to estimate but the hundreds of officially reported cases are believed to be only the tip of the iceberg.

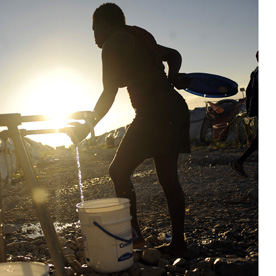

When Haiti’s devastating earthquake struck, it decimated Port au Prince and tore apart the social fabric of the city. Tens of thousands still live in makeshift camps.

Many women not only lost their homes but their families in the earthquake – leaving them vulnerable and exposed. The camps they took refuge in are poorly lit and poorly policed.

According to reports the rapists are predominantly armed men who roam the camps after dark. Few are ever caught, and virtually no one has been prosecuted.

Fritzna must also raise the child of her rapist.

She told Channel 4 News: “When I came in he grabbed me in the dark and held me. There were two others with him. As I was struggling he grabbed a large bottle of rum and smashed me on the head. They were still holding my wrists when I went down,” she told me.

When they released him, he came after me with other men, to kill me and the child. Now I’m on the run from them. Fritzna, rape victim

She revealed the blood stained night dress she had been wearing when she was attacked. She said she kept it with her in hope of justice. It was the only evidence she had of what happened to her.

Fritzna says her hope of justice has gone. The man she says raped her was released without trial. She’s thrown the night dress away. Now she says the man is trying to kill her because she reported him to the police.

“When they released him, he came after me with other men, to kill me and the child. Now I’m on the run from them.”

“They’re still after me along with my sister. They came after her, to kill her as well. One of them pulled a knife on her while she was out in town.”

“When I see the child it brings back those memories. It’s become like a scar for me. People always curse me, they say there she is with a rapist’s child in her hands. My child has no father so I need help from other people. It gives me a lot of the problems. There are times when I feel such humiliation I could kill myself and the child and just finish with everything.”

Legal failings

The cracks in Haiti’s legal structure were evident before the earthquake but the lawlessness of the displacement camps has further exposed its many problems.

Mario Joseph, a prominent human rights lawyer in Port au Prince said he is handling 50 rape cases at the moment. None have yet led to a conviction.

“Sometimes the cases are blocked at prosecution level, sometimes during the investigation. They tend not to want to take them on and all the judges are men. That means in these cases they are not very sensitive,” Joseph said.

At one of Port au Prince’s main police stations next to the city’s biggest camps nobody was keen to talk to me. After an hour of being given the run around, I was finally able to talk to a senior officer. She claimed there’s little the police can do.

“We do what the law says we can do. We file the complaint and refer them on or send them to hospital. If there is any possibility to arrest someone we will,” she said.

With a widespread lack of trust in the authorities, it has been left to people within the camps to deal with the problem themselves.

Read more: Searching for the families of Haiti's lost children

Kofaviv, a women’s group which offers support and protection for rape victims, was founded by women who were raped themselves during another period of Haiti’s turbulent history. It is recruiting men to help with the project partly to protect women in the camps, but also to educate other young men about rape.

Sammy Bazile lives in the Place Petion camp with his wife, and says the group is making a real difference.

“Rapes happen. I might not have seen it with my own eyes but they happen. It is something you are always hearing about. I cannot speak for other camps but as far as Place Petion is concerned, since this group’s been here its gone right down,” Sammy said.

Despite Kofaviv’s work, Sammy says he is still concerned about the safety of his wife.

“It’s something that is almost inevitable. I can’t not be worried. If it’s my wife who happens to be there when they turn up, they will rape her.”

But the tragic reality for many girls and women in Haiti is that while the camps remain, the rapes will continue.