Inspire: Inside the al-Qaeda magazine

It is the glossy magazine where terrorists are the celebrities and the only recipes are for bombs like the ones used in the Boston Marathon attacks. Channel 4 News looks at al-Qaeda’s Inspire.

With its slick yet slightly tacky design, its promos and newsflashes, Inspire has the look of an in-flight publication, though for obvious reasons, it would be rather worrying if you found it on an aeroplane.

One of the bombs featured in an issue – involving a pressure cooker – meant the magazine was heavily cited in coverage of the Boston bombings, apparently being the publication of choice for the two men suspected of carrying out the attacks, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. US investigators later confirmed that Tamerlan was an avid reader.

Inspired by the former radical cleric Anwar al-Awlaki of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the magazine goes far beyond your average dentist’s waiting room reading.

It sells itself as a terror training manual – a touchstone for the jihadi fraternity, with numerous features on how to make explosive devices and articles on inspirational terorrists.

Inspire’s credibility

The magazine got off to an inglorious start when it was launched in July 2010. Amid much fanfare about being the online English-language publication for AQAP members, supporters and potential sympathisers, only three pages of the 67-page magazine actually made it onto the web. A fourth page showed nothing but garbled images.

Three years later, it may have passed through the hands of a credible designer, but it still has far to go before it reaches the heights of sophistication – particularly when it comes to the most notorious editorial content: how to carry out a terrorist attack.

Flicking, or indeed, clicking through Inspire – it is only available online – it immediately becomes clear who the intended readers are.

The attack plans do not come with a star rating or estimated preparation time, but they are described as “easy to do”, which must be reassuring for amateur jihadists in the Four Lions mode.

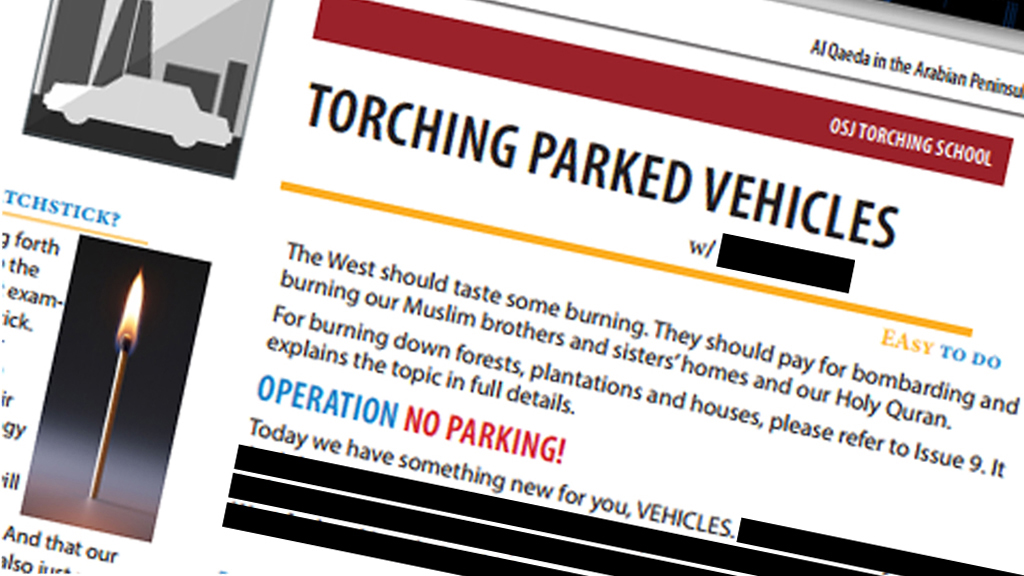

Towards the back of the latest edition is an article on “torching parked vehicles”. In the “procedure” section is the following helpful tip: “Find a deserted parked car.”

It then goes on to describe what is required for a fire to burn. For readers who never made it to primary school, that’s fuel and a source of ignition. In this case, the source is a matchstick, a picture of which is handily printed beside the article, for readers unaware of what one looks like.

This edition also contains other ideas for damage involving cars. Next to a picture of an instrument readers are urged to make to wreck a car, Inspire suddenly morphs into a colour children’s supplement from a weekend newspaper with instructions on how to make a mask for trick-or-treating on Hallowe’en. “Scary, isn’t it?”, the writer adds.

That is not to say that everything in the magazine is as banal. It uses disturbing images of mangled cars along with statistics on the number of people who died in road crashes each year, and how many of them are left injured or disabled.

‘Suspicion’

Elsewhere in the magazine is an entire page devoted to the influence the magazine apparently has, and how threatening it is to the authorities.

It joyfully cites a quote from a US newspaper, with an almost audible punching of the air in celebration: “This week, the magazine surprised some when it released a double issue. The glossy, highly produced online magazine has become the Vanity Fair of terrorism. It is clear that al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula has found new publishing talent.”

Maybe, but what is also clear is that Inspire has created as much suspicion as inspiration among potential readers. One jihadist forum describes it as a product of the CIA and MI6, and another suggests that it should be deleted as soon as it is read.

In the UK, possession of the magazine may well land you in trouble.

Last week, four men closer to home in Luton who discussed blowing up a Territorial Army base by sending a bomb in a toy car were jailed; one of the offences was possession of Inspire magazine.

Although the magazine is not technically banned, according to Scotland Yard, the men in the Luton case who had it were charged and convicted under Section 58 of the Terrorism Act, which relates to possession of a document or record containing information likely to be useful to prepare terrorist acts.

It has also been enough of a threat that it has apparently been hacked by British intelligence services, who reportedly broke in and replaced one set of bomb-making instructions with a recipe for cupcakes.

Perhaps the officials had read the article entitled “Make a bomb in the kitchen of your mom” and just couldn’t resist adding some all-American home cooked goodness.

Operation Cupcake may have been a hoax, but one which would be hard to spot. Perhaps next time they could do a feature on “Jihad: what not to wear”.