Iowa makes its choice – but why does it matter?

In America’s election year, Iowa – the first state to choose who should become the Republican party’s nominee – is where the presidential campaign begins in earnest, writes Felicity Spector.

It is Iowa’s moment: millions of advertising dollars, thousands of campaign hours, hundreds of stump speeches, handshakes and coffee shop chats. Tonight more than 100,000 party activists will crowd into schools, libraries, churches and homes, to cast the very first votes of the Republican presidential campaign.

Iowa has jealously guarded its first-in-the-nation status, state law proclaiming that no other state or territory may be permitted to hold an earlier vote. The Midwestern, largely rural state is by no stretch of the imagination a representative sample of the country as a whole. Iowans are whiter, older, and wealthier than the average American, while those who actually turn up to caucuses – some 6 per cent of eligible voters – are more politically extreme.

Yet all eyes will be on the Hawkeye state tonight. At seven o clock, at more than 800 designated voting places across the state, anyone who is over 18 and a registered Republican can show up to take part. There are speeches by representatives of all the candidates, and then everyone votes for their choice by paper ballot.

More from Channel 4 News: Jobs, debt and the war dominate Iowa caucus

The vote itself is not binding. The activists in the room will also elect delegates to the Iowa state convention, who in turn will pick delegates to the GOP national convention in August – the body which actually chooses the presidential nominee. These delegates are not mandated to back their precinct’s preferred candidate. So tonight is more of a straw poll than anything else.

Pounding the pavements

Still, in the election lore of American tradition, Iowa – and the first-in-the-nation primary in New Hampshire, held next Tuesday – have acquired mythical status. It is not so much about being a reliable political weathervane, but a reality check.

Both Iowa and New Hampshire require candidates to meet voters face to face, to pound pavements and show up at local events. The sheer number of debates has kept many of this year’s field away from the traditional stump – but Rick Santorum, who has visited every one of Iowa’s 99 counties, has attributed his last-minute surge to his steady, hard-working slog around the state.

For years the pundits have been trying to oust Iowa from the top of the election calendar. After all, it has a pretty poor record in selecting the eventual winner in Republican contests. Out of the last five contested races, only one candidate, George W Bush, won in Iowa, then made it all the way to the White House.

But it is equally true that no-one has won their party’s nomination without emerging in Iowa’s top three. Apart from John McCain, that is, who opted not to bother campaigning in Iowa in 2008, but became the candidate nonetheless.

The long game

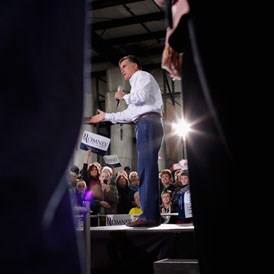

No, this one is about the long game. For Mitt Romney, a strong showing here, plus his fairly inevitable victory in New Hampshire next week, ought to consolidate his mantle as presumptive nominee – and give him that “air of electability” that he craves.

For the likes of outliers like Ron Paul or Rick Santorum, both showing strongly in opinion polls, it is less clear. The party still sees the 76-year-old Tea Party veteran Paul as unelectable – and despite this week’s sudden surge, Santorum lacks the finance and nationwide organisation to keep the neccessary momentum going over the weeks to come.

Although several states have flouted the Republican party’s new rules to spread out the nominating process, by holding their primaries before the end of February, they will still account for just 8 per cent of the total votes needed to clinch victory at this summer’s convention. In a race that has been so volatile, a lack of early clarity means it could all be to play for well beyond Easter.

Money matters

So however unrepresentative, however quirky, what happens in Iowa tonight cannot be ignored. It is why the candidates – and the supposedly independent groups of wealthy individuals and corporations which swing their unlimited funds behind them – have splashed out around $12.5m on political advertising in this tiny state, according to the New York Times. That is roughly $100 for every voter who’s expected turn out tonight. And as late as the weekend, almost half of them claimed they still had not made up their minds who to support.

But one thing is certain. Whatever the Iowa caucus is not good for, it has always been good for surprises.

Felicity Spector is the US politics writer for Channel 4 News. Follow her on Twitter @felicityspector