IVF imaging ‘breakthrough’ could boost fertility

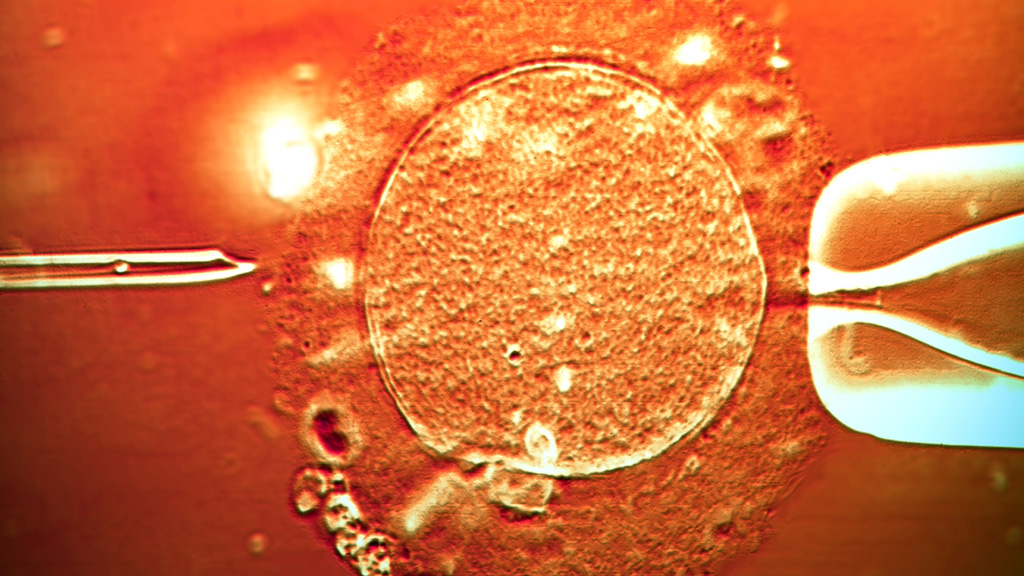

Thousands of infertile couples could see their chances of having a baby improved following a new technique which assesses the quality of IVF embryos before they are implanted.

Using time-lapse photographs researchers claim they are able to spot developmental delays in the embryo at crucial stages allowing them to select “low-risk” embryos which are not likely to have chromosomal abnormalities.

On average only about 24 per cent of embryos implanted into women in the UK lead to live births. This technique claims to increase chances by 56 per cent, compared with all embryos. However the study, which has not been clinically trialled, has been deemed too small to be definitive by fellow scientists. It followed just 46 embryos through to birth.

Alison Campbell, embryology director at IVF clinic operators CARE Fertility, who led the research, said: “Our key finding was that embryos from the high-risk class (for aneuploidy) showed no implantation at all.

“The highest implantation as well as live birth potential was found for embryos from our low-risk class. Normally, IVF embryos in an incubator are checked manually each day by embryologists, but the time-lapse cameras are able to do this automatically by taking pictures every 10 minutes without interfering with embryo development.”

Read more: the ethical obstacles to an IVF breakthrough

Miscarriage risk

Eleven babies were born from the low-risk group (61 per cent success rate), compared to five from the medium risk group (19 per cent success rate) and none from those deemed high risk.

High-risk class is common in human embryos and a major cause of fertility treatment failure and miscarriage. Most affected embryos will not implant in the womb. If they do, they can result in a miscarriage or the birth of a child with a chromosomal disorder such as Down’s syndrome.

The IVF community needs a prospective randomised controlled trial before it can be recommended to patients. Sue Avery, Birmingham Women’s Fertility Centre

Traditional techniques for spotting abnormalities involve removing cells from embryos and genetic screening.

Independent scientists not involved in the work agree this is an exciting new approach, but they also stress that a randomised trial is needed to compare women with pregnancy rates using time lapse imaging with those who use conventional techniques.

‘Exciting new approach’

Director of the Birmingham Women’s Fertility Centre, Sue Avery said: “Unfortunately the study does not compare this exciting new approach with standard practise in embryology in which embryologists already look for the best embryos to place in the womb.

“Until the new technique is compared to current practise we cannot know whether different embryos are being chosen. The IVF community needs a prospective randomised controlled trial to prove that the new approach delivers better results before it can be recommended to patients. Until then this study is an interesting piece of science but not clinically significant.”

The research was published in the journal Reproductive BioMedicine Online.