Libya removed from Human Rights Council

Libya becomes the first member state to be suspended by the UN Human Rights Council after a day of tension and the prospect of military action and civil war, as our Correspondents in Libya report.

Libya has been suspended from the UN Human Rights Council after recent protests across the country led to accusations of vicious treatment to its people by Colonel Gaddafi‘s regime. It is an unprecedented move by the Council, and comes after days of pressure from leading United Nations delegates and adds to the increasing pressure on Gaddafi to listen to the international community, and stand down.

UK Foreign Secretary William Hague released a statement saying: “I strongly welcome the UN General Assembly’s resolution to suspend Libya from the Human Rights Council. This outcome, which the UK has pressed for with partners, demonstrates the unity of the international community and its commitment to hold the Libyan regime accountable.

Crimes will not go unpunished and will not be forgotten; there will be a day of reckoning and the reach of international justice is long. Foreign Secretary William Hague

“Libya’s suspension from the Council is unprecedented. But it is absolutely right that a regime that has failed so shamefully in its responsibility to its people and that has been referred to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court should not be allowed to continue to enjoy the rights of membership.

“Suspension from the Council puts yet more pressure on the Libyan regime to listen to the clear message of the international community; crimes will not go unpunished and will not be forgotten; there will be a day of reckoning and the reach of international justice is long.”

Prime Minister David Cameron earlier justified calls for a no-fly zone to be imposed over Libya, saying: “We might need to have a no fly zone in place very quickly.”

He said: “It’s not acceptable that Colonel Gaddafi can be murdering his own people, using aeroplanes and helicopter gunships … and we have to plan now to make sure that if it happens we can do something to stop that”

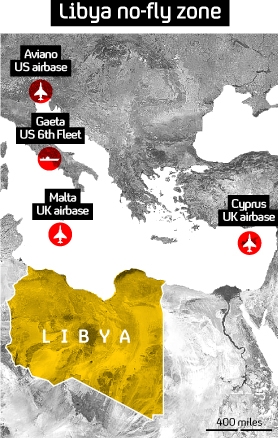

The no-fly zone could be managed from four sites, two UK airbases in Malta and Cyprus, plus US forces from their fleet moored at Gaeta off the Italian coast and their own airbase at Aviano in Northern Italy.

Mr Cameron’s strong military assertions over the last few day have been met with dismissive comments from the Libyan leader’s son, Saif Gaddafi. He described Mr Cameron’s threat of military action as “like a joke, for the whole security council”, before warning that if action were to be taken “we are ready, we are not afraid.”

Reporting from Tripoli, Channel 4 News Foreign Affairs Correspondent, Jonathan Rugman, said it was not clear where any internal spark might come from to help unseat Gaddafi.

“He has over 200 tanks to defend the city. He has his propaganda machine. He has his supporters. It isn’t obvious that there is a general who is ready to oppose him. No member of his family is suggesting he should go.”

No-fly zones - would it work in Libya?

"No-fly zones (NFZs) are complicated to set up and then expensive and difficult to operate; but they can certainly work in preventing a country engaging in major air operations - fast jet and bomber sorties over reasonably long distances - or in preventing aircraft from other countries coming in to help an outlawed government, or bring in supplies for it," Michael Clarke, Director of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) told Channel 4 News.

"If the political objective is big enough, NFZs may be worth establishing in such situations. But if the objective is to stop a leadership attacking its own people from the air - perhaps using helicopters or aircraft over short distances, where their flying times are measured in minutes - then it is very difficult to create an effective NFZ. It may have a political impact and be a demonstration of the resolve of the outside world to oppose a tyranny, but it is equally likely to lose credibility if it fails to prevent civilians being attacked from the air.

"NFZs that were established over Iraq and then Bosnia in the 1990s showed exactly this pattern. They prevented major air operations but could not prevent low-flying and helicopter operations by the Serbs and by Saddam Hussein's Iraqi air force, and the credibility of both NFZs became stretched as a result. The only sure way to prevent Libyan aircraft from being used in the civil war that is now developing around Tripoli is for western forces to bomb Libyan airfields and destroy the infrastructure of what airpower Gaddafi still has. But that would be the opening of a whole new ball game."

Michael Clarke is the Director of the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies.

And the French Foreign Minister, Alain Juppe, stressed that any military action would require a UN military mandate.

“Different options can be assessed, notably a no-fly zone,” he said. “But let me put it clearly here – no intervention will happen without a clear UN Security Council mandate.”

Meanwhile, despite Hillary Clinton’s assertions on Monday that “nothing was off the table”, rhetoric from the US was steering away from the use of a no-fly zone over Libya. Despite mobilising warships and military aircraft to nearer the area, General James Mattis, commander of US Central Command, warned a Senate hearing that a no-fly implementation would be “very challenging”.

He went on to say that such a move would be a course of genuine military activity.

“You would have to remove air defence capabilty in order to establish a no-fly zone, so no illusions here. It would be a military operation – it wouldn’t be just telling people not to fly airplanes,” he said.

In a prepared statement to the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, Mrs Clinton said: “This is an unfolding example of how we use the combined assets of diplomacy, development and defence to protect our interests and advance our values.”

Meeting the relatives of those killed in notorious Gaddafi massacre

As I took off my shoes to enter the house, I realised this would be emotional, writes Channel 4 News International Editor Lindsey Hilsum.

About a dozen women and men were sitting on sofas around the living room, each silently holding up a photograph of a son, a brother, a husband, a father.

They were relatives of some of those killed in the most notorious massacre of Colonel Gaddafi's rule, when security guards machine-gunned 1,200 men in Abu Salim prison in 1996. It was their story which sparked the uprising in Benghazi.

Over the last four years, the families in Benghazi have demonstrated every Saturday, demanding justice and answers. Where are the bodies? Who was responsible? Who will pay? When their lawyer, Fathi Terbil, was arrested on 15 February, they came out again, but this time, thousands of others joined them.

This was the spark that lit the fuse in Benghazi.

"We, the Abu Salim families, ignited the revolution," he told me. "The Libyan people were ready to rise up because of the injustice they experienced in their lives, but they needed a cause. So calling for the release of people, including me, who had been arrested became the justification for their protest."

Mr Terbil still fears for his life, believing that Colonel Gaddafi's agents could still be in Benghazi.Every day more photos appear outside the courthouse, where Benghazi’s new anti-Gaddafi administration is based. Some families have been so terrified for so long, they've never before dared to admit that their relative had disappeared.

Read more in Lindsey Hilsum's blog: Meeting the families left behind by Gaddafi's prison massacre.