More people with Down’s syndrome developing dementia

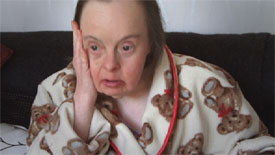

People with Down’s syndrome are at greater risk of developing dementia much earlier than the general population. As they age, their families and carers are now struggling to cope, writes Tim Lawton.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- subtitles off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

People with Down’s syndrome are living longer than ever before. Since the 1980s their life expectancy has doubled and many now live into their 60s.

But for the estimated 60,000 people with Down’s syndrome in the UK this development is coupled with the startling knowledge that people with Down’s are significantly more at risk of developing dementia than in the rest of us. Not only that but they also develop it at a much younger age – 30 to 40 years earlier than the general population.

Charlene is just 29 and was diagnosed with dementia six years ago. Her mum has witnessed her change from a fun-loving, karaoke-singing young person to “an old lady”. Previously unaware of the high prevalence of dementia in people with Down’s, it was a shock for the family to learn that Charlene was developing the disease in her early 20s.

Charlene is unusually young to start developing dementia, but studies do show that the risk increases dramatically with age. By 50, half of people with Down’s are at risk of developing dementia, and this, in turn, is presenting a huge burden to families and services.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- subtitles off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

With an aging Down’s population, Diana Kerr, a leading expert in the dual diagnosis at University of Edinburgh, worries that local authorities are not ready to meet the increasing demands of this population – partly because of a false perception that people with Down’s don’t live long enough.

Often changes in personality are the first sign of dementia, and a diagnosis is crucial for accessing the right services. It also means the family or carers can begin to change their responses and environment to make life more manageable for the person with Down’s.

In Bradford, Nicole has Down’s syndrome and lives with her sister Jackie. Nicole’s changing behaviour is causing the family and her daycare service great strain. At 52 years of age there is a high probability this change in her character is due to the onset of dementia.

Recently has she been allocated a social worker to help begin the diagnostic process with Bradford District Care Trust. Dr Baylis is part of a multi-disciplinary team which will try to diagnose Nicole. She has other health conditions that could mimic dementia-like symptoms, so a clear diagnosis takes some time while other problems are ruled out.

But Diane Kerr insists that many options for carers are not costly and that simply training families and staff “who are supporting people with dementia to get into their world, instead of expecting them to get into our world,” could greatly improve the situation for all concerned.

However, the default care option for many people with Down’s no longer able to remain at home is to be placed in a care home for the elderly. Diana Kerr’s findings warn that this is generally not the best solution. It may be cheaper than specialist dementia care for those with a learning disability, but there is often a lack of understanding among staff about the unique care needs involved.

Down's syndrome facts

- Around one in every 1000 babies born in the UK will have Down's syndrome.

- There are 60,000 people in the UK with the condition.

- Although the chance of a baby having Down's syndrome is higher for older mothers, more babies with Down's syndrome are born to younger women.

- Down's syndrome is caused by the presence of an extra chromosome in a baby's cells. It occurs by chance at conception and is irreversible.

- Down's syndrome is not a disease. People with Down's syndrome are not ill and do not "suffer" from the condition.

- People with the syndrome will have a degree of learning difficulty. However, most people with Down's syndrome will walk and talk and many will read and write, go to ordinary schools and lead fulfilling, semi-independent lives.

- Today the average life expectancy for a person with Down's syndrome is between 50 and 60. A considerable number of people with Down's syndrome live into their 60's.

Information by The Down's Syndrome Association

For Elaine in Cardiff this is something that she worries about daily. She cared for her daughter Mandy until dementia rapidly took hold in her 40s, when the burden on Elaine became too great. She ended up in hospital and Mandy was placed in a local care home.

Elaine visits the care home daily, and pushes to make sure that Mandy receives as much support as she can get. Where she thinks there is a shortfall in the available support, Elaine tries to fill it herself – such as trips to the physiotherapist so Mandy can stand for just a short time every week. Nationally, there are few facilities that cater specifically for those with Down’s syndrome and dementia. As more and more people develop dementia, experts warn that, due to a lack of resources, more will end up in homes for the elderly, like Mandy.

While families and services provide varied support to people with Down’s syndrome, scientists at Cambridge University are seeking treatments that could prevent future generations getting dementia at all. Professor Tony Holland has recently received funding from the Medical Research Council for a four-year study into a protein called amyloid.

People with Down’s have unusually high levels of amyloid in the brain, and Professor Holland wants to find out if this is the driving force behind dementia in those with Down’s syndrome.

If the study concludes that this protein is the key factor, the next step will be to find treatments that reduce the amount of amyloid being deposited in the brain – and thus attempt to prevent the onset of dementia in the Down’s population.

Furthermore, it might offer key insights into the role of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease in the general population.

However until a medical breakthrough can defeat dementia, Diana Kerr fears that recent improvements in quality of life for people with Down’s could quickly regress.

“If we do not do something about the needs of people with Down’s as they get older and have developed dementia, they will go back into the institutions that we have spent the last 20, 30 years trying to get them out of – long-stay units where they are left in a bed, where they can restrain people with chemicals so they don’t have to tie them down.

“And we’ve gone back 30 years. You know that thing about the mark of a civilised society is the way we support vulnerable people? Well, that would be a pretty big indictment.”

Tim Lawton is a producer/director for True Vision Productions