Mother who found comic relief after toddler son’s death

Channel 4 News reporter Katie Razzall meets a mother who turned a personal tragedy into graphic art.

When the illustrator Nicola Streeten told fellow students on her MA course that she was planning to turn the death of her son into a comic, the reaction was entirely negative. “Too depressing” she was told, “so boring”.

That was three years ago. But she persevered, her cartoons appearing first in a magazine and now in a remarkable book, Billy, Me and You.

She and her husband went through the worst experience any parent can imagine. Two-year old Billy, their first born, died just 10 days after being diagnosed with congenital heart problems. The book that his mother has written all these years later is sad, of course, but also uplifting, illuminating, and even funny.

Nicola Streeten told Channel 4 News: “I didn’t want to do it as therapy. We had therapy at the time. It’s about constructing a narrative around something that happened. It’s about how we, as people, respond to grief and loss and how it affects people around us… maybe there’s a similarity in how we, as humans, deal with it.”

The former teacher only started drawing cartoons to cheer herself up after Billy died.

Bereavement is something all of us go through at some point; unusual, though, to turn the experience into a comic. Billy, Me and You isn’t the only graphic memoir looking at the subject of grief and death. Also coming out is Tangles, a comic by the New York author, Sarah Leavitt, about her mother’s descent into Alzheimers.

So what does the genre provide that more conventional forms might not?

With the graphic novel has an immediate impact. It gives the emotion as well as what I’m saying. Nicola Streeten

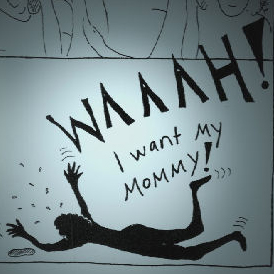

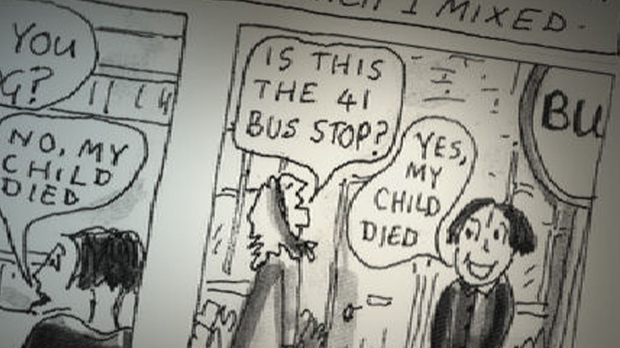

“It acts as a shorthand, says Streeten. “It cuts out everything superfluous. With the graphic novel, you can say two things in one square. The symbols, the images, instantly tell the reader, it has an immediate impact. It gives the emotion as well as what I’m saying.”

Her book is full of poignant moments: “I am not a mother, but I am not not a mother” she says, at one point. Then there’s the empty realisation that Billy’s bereaved parents can go out without getting a babysitter. And the sunflowers planted by Billy that wilt on the day of his operation.

Child bereavement counsellors are already saying the book will help other parents trying to cope with the death of a child.

It is also perhaps a guide about how others should behave. Streeten gives marks out of 10 to people’s reactions to the news that Billy died. “Oh, my friend’s baby died – in fact I helped her through it” gets minus 20 out of 10. “Sorry” gets full marks.

Nicola Streeten is testament to the power of time as a healer. She wrote a diary when Billy died. Only years later was she strong enough to look at it again. She says it was a real insight into how time can change your memories of a traumatic event. She remembered crying for two or three days after Billy died. The journal records her crying every day for a year.

Sixteen years after his death, and with a daughter of 14 who “saved” Ms Streeten and her husband, Billy, Me and You turns a deeply personal, but perhaps universal, experience into art.

Quite simply, Nicola Streeten has had the “best year creatively about the worst thing that ever happened to me in my life.”

Child Bereavement Charity website: www.childbereavement.org.uk

Hotline: 01494 568900