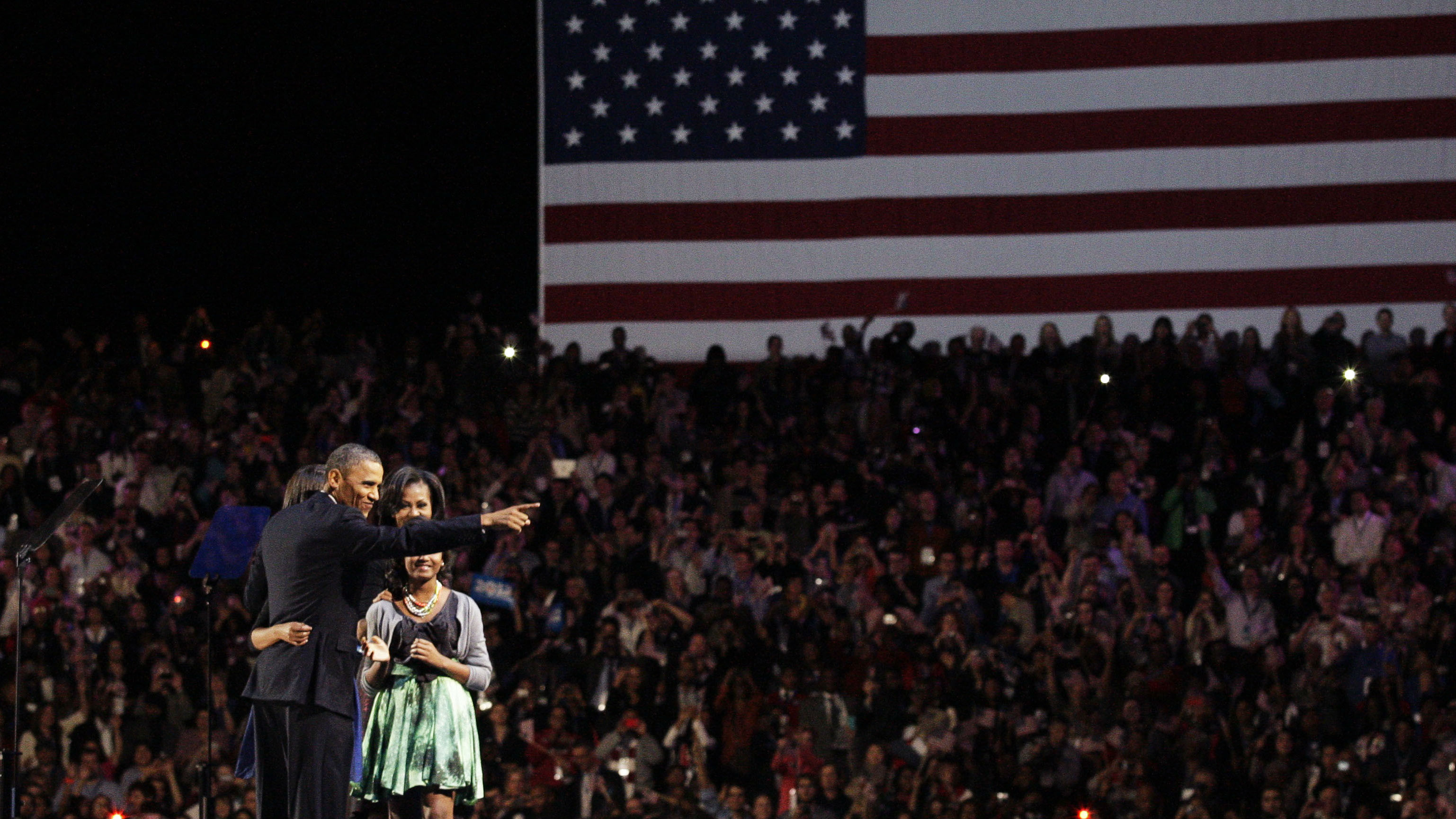

Obama’s pledge: Change you can believe in, again?

“Tonight you voted for action, not politics as usual” Obama told supporters last night – pledging to break the partisan gridlock which has paralysed Washington. But can he really change things?

Barack Obama has promised hope, and he has promised change: echoing the pledges of four long years ago, when the dream of a different kind of politics led many to believe that Washington would never be the same again.

But – and there will be no hurricane metaphors here, for this was no political storm to sweep all before it – Washington is in gridlock: despised and rejected by voters wearied by constant partisan bickering and the still nastier rancour of the long election campaign.

For if America has emerged into the grey dawn of election day plus one, as divided as it ever was before, so too have its political masters. Obama may have won his historic second term, but the margin of victory was tight.

Voters are almost evenly split between the two parties: split, too, on almost every major issue of the day. Ideologically, today’s America is literally polls apart. Down Pennsylvania Avenue, on Capitol Hill, division also reigns: the House will stay in Republican control, while Democrats keep the Senate, picking up some unexpected gains at the expense of Republicans doomed by their controversial remarks on rape.

There are a host of new women in both Houses: the first openly lesbian senator.

If there is a mandate, it is a mandate for both parties to find common ground and take steps together to help our economy grow and create jobs. John Boehner, House Speaker

From their leaders, all the talk this morning suggested a mood for compromise: House Speaker John Boehner declared: “If there is a mandate, it is a mandate for both parties to find common ground and take steps together to help our economy grow and create jobs.”

And it was a symbolic gesture perhaps, but despite all the personal bitterness of their election battle, Obama insisted he wanted to sit down with Mitt Romney and find ways of working together.

The sentiment from Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell was less clear: he offered to meet the president halfway, but only “to the extent he wants to move to the political centre”, with proposals “that actually have a chance of passing.”

Defensive in defeat?

On the face of it, the conservatives are on the defensive. Ten of the defeated GOP House representatives were from that insurgent cohort of Tea party activists elected in 2010: the party’s huge shift to the right did not prove popular with swathes of voters, especially women, young people, and minorities.

And in the cold, hard reality of a wintry Washington morning, there are cold, hard questions on the economy. On the immediate agenda, there is a crucial package of tax hikes and sweeping cuts in spending to deal with: a deal to forge, to avoid the looming “fiscal cliff” in January.

And, don’t forget, there have been grand promises of bipartisanship before, of reaching across the aisle to forge a poltiical consensus with his Republican rivals, to work for American interests rather than party concerns.

It didn’t happen then, and Washington has languished in the depths of its self-induced frustration. If it is to happen now, then political leaders will have to get beyond the same old arguments that have doomed the nation’s politics in the past.

It is certainly what the voters have clamoured for, at least the vast majority who have been desperately searching for that elusive change in Washington and the magic of the hope that was promised four years ago and that has now been promised again.

The people, though, have had their day. Now it is up to the President and Congress to heal a divided nation, and give America the leadership and the unity that it craves.

Felicity Spector writes about US politics for Channel 4 News