Is Dawkins right about ‘anti-scientific’ fairy tales?

Richard Dawkins voiced concerns this week about the effects of supernatural fairy stories on young minds. But magical folk tales continue to hold an irresistible appeal for artists and writers.

The God Delusion author was quoted as asking an audience at the Hay Festival if it was “pernicious to instil in a child the view that the world is shaped by supernaturalism” and asking: “Is it a good thing to go along with the fantasy of childhood… or should we be fostering a spirit of scepticism?”

Prof Dawkins has since said newspapers and broadcasters have taken his words out of context and written misleading headlines about his remarks. He has clarified that he thinks that fairy tales might have “a beneficial effect” and “probably” do not “inculcate supernaturalism into a child”.

The scientist, who is a prominent atheist and proponent of critical thinking, has repeatedly questioned the wisdom of exposing children to tales of the supernatural in the past.

<!–

–>

In a 2008 interview with More4 News, Prof Dawkin said: “I don’t know what to think about magic and fairy tales.

“I would like to know whether there is any evidence that bringing children up to believe in spells and wizards and magic wands and things turning into other things… it is unscientific, I think it’s anti-scientific, and whether that has a pernicious effect I don’t know.”

He added: “Looking back to my own childhood, the fact that so many of the stories I read allowed the possibility of frogs turning into princes, whether that has a sort of insidious affect on rationality, I’m not sure. Perhaps it’s something for research.”

Educators and prominent writers have leapt to the defence of the fairy story as an art form and a means of firing children’s imaginations, while denying that the form encourages them to blur fact and fiction.

The novelist Jeanette Winterson says Prof Dawkins is making a “category error” when he worries about children believing that frogs can turn into princes, saying: “Reason and logic are tools for understanding the world. We need a means of understanding ourselves, too. That is what imagination allows.”

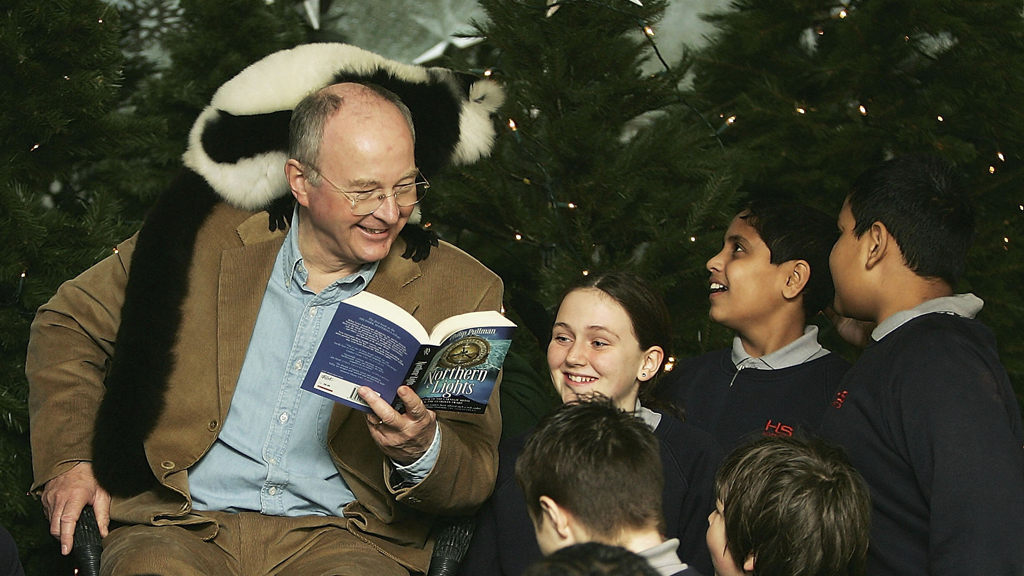

Philip Pullman, who like Dawkins is a prominent atheist, has previously leapt to the defence of the fairy tale.

The His Dark Materials author, who published a re-telling of the Grimm tales in 2012, told the Guardian: “Dawkins is wrong to be anxious.

“Frogs don’t really turn into princes. That’s not what’s really happening. It’s ‘Let’s pretend’; ‘What if’; that kind of thing. It’s completely harmless. On the contrary, it’s helpful and encouraging to the imagination.”

As long ago as 1939, Lord of the Rings author JRR Tolkien rejected the idea that being exposed to Norse mythology as a child affected his ability to distinguish reality from fantasy.

<!–

–>

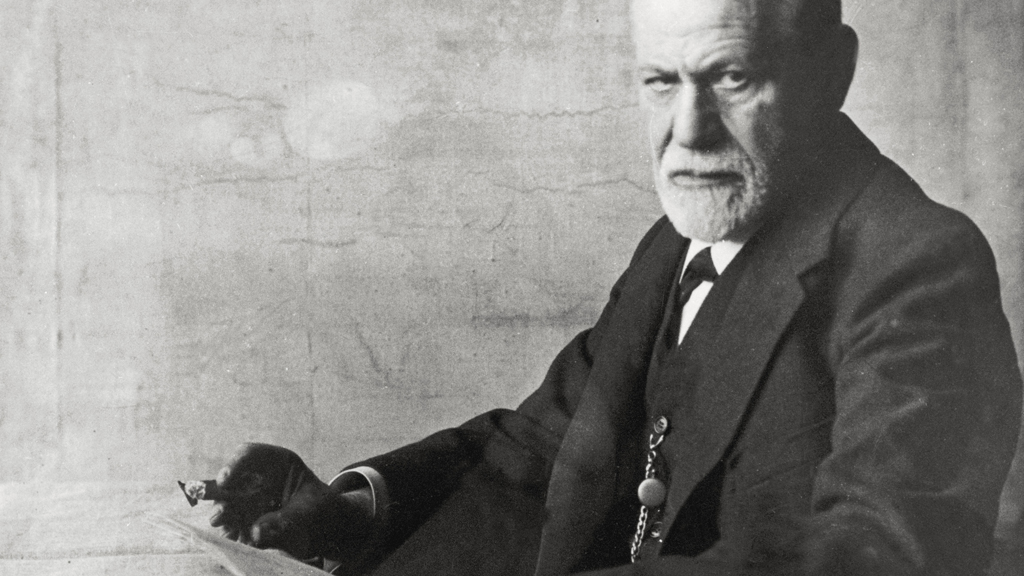

The father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, first noted how images and themes from well-known fairy tales appeared in the dreams adult patients’ dreams in 1918. His disciple Carl Jung went on to develop a theory that folk tales were a window into humanity’s “collective unconscious”.

Bruno Bettelheim used psychoanalytic concepts to interpret Grimm fairy tales in The Uses of Enchantment, concluding that the stories are designed to help children cope with the developmental struggles of growing up by offering a vision of a brighter future.

He wrote: “The unrealistic nature of these tales (which narrowminded rationalists object to) is an important device, because it makes obvious that the fairy tales’ concern is not useful information about the external world, but the inner process taking place in an individual.”

Some have claimed to find echoes of historical events in traditional stories. Could the tale of Hansel and Gretel wandering alone in the woods be a folk memory of the Great Famine of the 14th century, when children were turned out to fend for themselves by starving peasants?