Street battle: America’s final, desperate push for votes

It’s up to you, Obama told supporters last night: Felicity Spector joined some of the hundreds of thousands of volunteers on both sides who are pounding the streets – fighting for every vote.

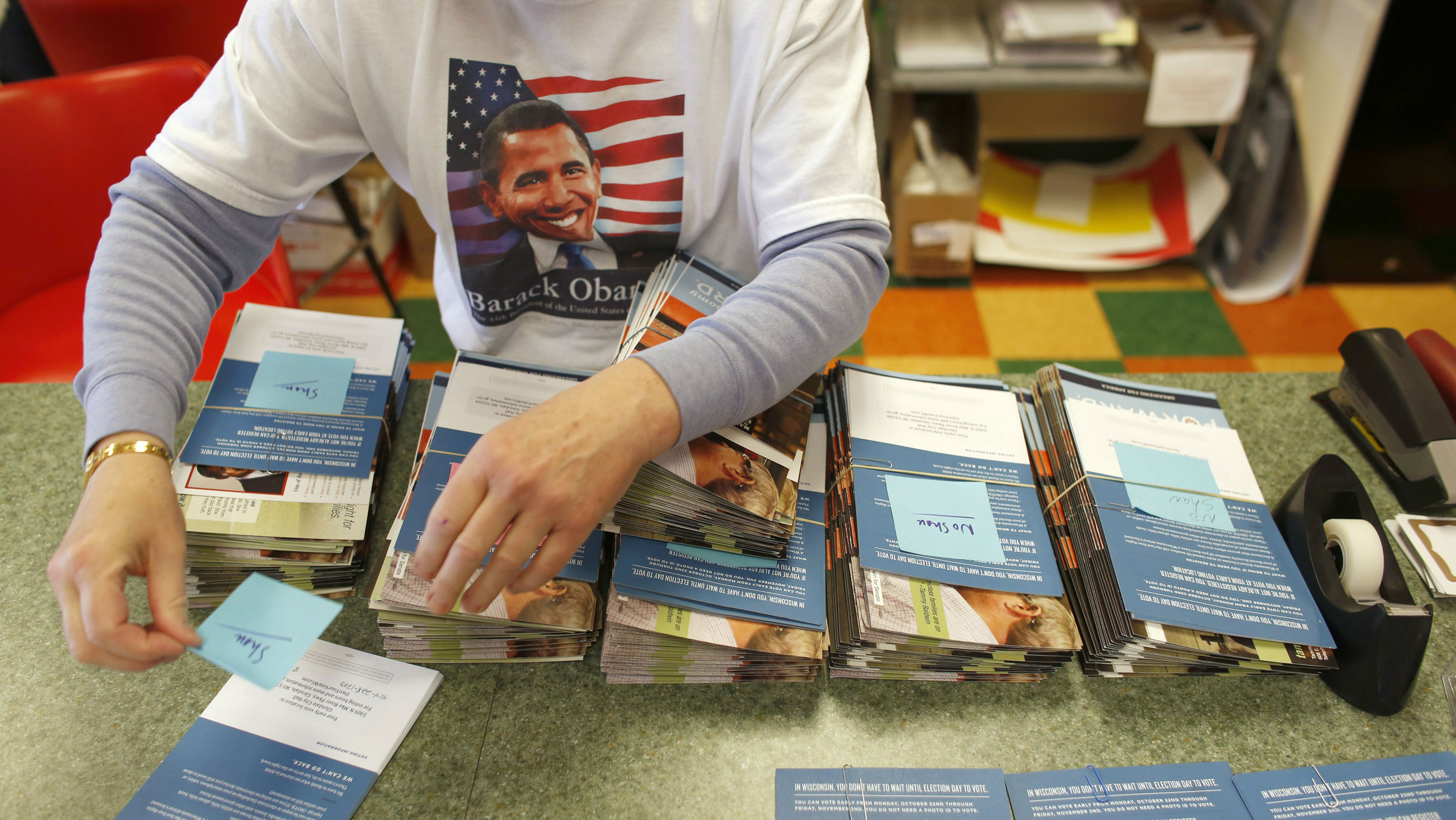

In a suburban living room in northern Virginia, a trestle table is piled high with dog-eared papers filled with voting lists. Rolls of Obama stickers jostle for space with boxes of granola bars, as volunteers crowd in for a last-minute briefing.

This is the ground war of the US election campaign: in this living room, and thousands like it across the battleground states, these are the people who are fighting for every last vote, votes that really could decide who wins the White House on Tuesday.

This is not the time to win anyone over, the volunteers are told: this is all about dragging Obama supporters out to the polls. There is a short script to learn: are you voting for Obama? What time do you plan to vote? Do you need a ride?

And out they go, armed with maps and GPS directions and lists of known supporters. This will be the third time these voters have been visited in the last few days, in a “get out the vote” operation that has been running day and night.

Inevitably, most people are out, or pretending not to be home. One man snaps through a locked door: “This is the sixth time you people have called on me! I told you already, my wife is voting Obama…” Others are more understanding – there are, after all, just two more days of this.

Now it’s all up to you. This is how democracy is supposed to be. Barack Obama

The Obama campaign believes this ground campaign, years in the building, will prove its secret weapon: in Virginia, for instance, it has 61 field offices, more than twice as many as the Romney campaign.

Across the handful of swing states, there are more than 5,000 “staging locations”, highly decentralised neighbourhood campaign offices set up in activists’ homes. It’s grassroots campaigning in its finest form: signing up volunteers on almost 700,000 shifts to get out the vote in the final few days.

These are people who really know their stuff. They have been working here for months, if not years. They know the ground, they know their communities. And nothing, goes the theory, is more effective than personal contact by a neighbour or someone you know.

House by house, street by street

The thousands of volunteers are often bussed in from out of town, or from states where the battle is not so crucial. A smartphone is as essential as the overbrewed vats of coffee. Many of those joining the campaign in Virginia come from DC: there are students, government workers, academics.

It is relentless. There is no time for sleep, precious little time to eat. “This is the 65th time this weekend I’ve given this canvas training speech,” says the cheerful middle-aged lady who has turned her home into a staging post. In the kitchen, her husband calls out: “There are bagels! Please, come help yourself to bagels!”

Between them, the Obama and Romney campaigns claim they have contacted 44 per cent and 41 per cent of likely voters respectively, by phone or in person. According to the Washington Post, the vast majority were contacted in the last week.

The Romney-Ryan Virginia headquarters in Arlington is a world away from a makeshift living room. On the seventh floor of a plush office block, where you need a special pass key to enter the lift, the phones are humming.

A stream of volunteers troop in and out, some off on canvass trips, others to work the phones, organised by 20 full time staffers who seem to be running on adrenaline and bags of popcorn.

Working the phones

In the phonebank room, 37 year old consultant Dana Hudson has taken a break to work on her computer. She has been helping out for six weeks, a couple of evenings after work. She says the response she’s got from voters has been really positive. ” It’s been amazing. You never get this kind of reaction here usually.”

Another helper, Deborah, doesn’t want to give her name because she works for the government. She says she joined the Romney campaign because her family were small business owners and hadn’t been able to take a pay cheque for two years.

“People really wanted Obama to succeed”, she says. “I wanted him to succeed. But it’s been a real disappointment.” She insists that everyone she has managed to contact has been very enthusiastic.

18-year-old Pierce Faragasso is spending his first day as a volunteer, admitting sheepishly that maybe he has left it a bit late to get involved. “I’m here with my roommate Craig. It’s pretty hard for us because our school is predominantly Democrat. Everyone just keeps talking about Obama.”

To hype up the phone bankers, there is a visit from a high-profile supporter: former head of the Small Business Administration Jovita Carranza, who has been sent out to mobilise the Hispanic vote, a group which appears to be overwhelmingly pro-Obama.

She gives a short speech about the importance of conservative values: someone asks a question about what they should say to a voter who is still unenthusiastic about the choice of Mitt Romney as Republican candidate. A huge gasp goes up when Carranza says her mother voted Democrat because someone paid her $5 if she did.

Relentless pace

The speeches over, the volunteers go back to their scripts, rolling those calls. For the voters of Virginia, it has been endless. There are stories of one man who took to answering his phone by barking “Romney!”, rather than “Hello”.

But there are just a handful of hours to go. The campaigns have more money than they can possibly spend, more miles than even the breakneck schedules of the exhausted candidates can possibly cover.

So it is down to this: phone calls, door knocking, troops of local people sleeping on strangers’ floors, driving borrowed cars, living on coffee and donuts and nerves.

“Now it’s all up to you,” Obama told supporters in Virginia this weekend. “That’s how democracy is supposed to be.”

In the battle for the White House in November 2012, one thing is clear: every vote will count. And that’s why those thousands of volunteers in Virginia, and the rest of the battleground states, are working as if their lives depended on it. For they have voters still to meet: and hours to go before they sleep.

Felicity Spector writes about US politics for Channel 4 News