The eurozone debt crisis that keeps repeating itself?

We track the repeat “crunch talks” which punctuate the eurozone debt crisis, as a global finance expert tells Channel 4 News Europe’s leaders are wrestling with an “ungovernable system”.

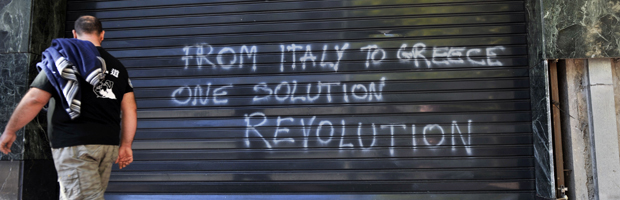

Is the drama surrounding the eurozone the crisis which refuses to die? The phone-hacking scandal, the Libya war, the hunt for bin Laden; all these major events have come and gone in the time that Angela Merkel and co seem to have been locked in different but similar “crunch talks” across Europe.

Since its birth on 1 January 1999 the European single currency has never been so talked about. So what exactly has been happening at all those meetings, summits and D-Days?

Rob Johnson is a senior fellow and director of the Project on Global Finance at the Roosevelt Institute.

He told Channel 4 News: “It is taking so long because it is not a mechanical problem, it is a political problem within a currency union where the nations do not regard one another as true members who they have to take care of.

“Germans do not consider Greeks or the Portuguese as equal to themselves.

“The European Central Bank (ECB) does not want to do a massive back door bailout and because the financial sector is too powerful to be forced to recognise and bear the losses they should be made to take.

Financial regulators have tolerated an ungovernable system. Rob Johnson

“It is also because financial regulators have tolerated an ungovernable system and they are terrified of what they would unleash in the derivative markets if they were to restructure these debts.”

So why is German leader Angela Merkel feeling the heat more than the other leaders?

“Merkel is at the vulnerable point where to save Europe she has felt that she had to risk her own reelection,” Johnson says.

“The crisis has now deepened to the point where she may need to risk disapproval in order to avoid a financial crisis that would doom her political future.”

More from Channel 4 News: What is the eurozone debt deal all about?

Channel 4 News looks back at the decisions made by Europe’s leaders in the many crisis talks so far.

January 2010

An EU report finds “severe irregularities” in Greek accounting procedures. The country’s budget deficit is revised upwards to 12.7 per cent from 3.7 per cent – more than four times the maximum allowed under EU rules. Worries begin to circulate about countries in a similar state of debt – Ireland, Portugal and Spain.

February

The Greek government sets out a raft of austerity measures aimed at controlling its budget deficit. Channel 4 News Economics Editor Faisal Islam compares the euro crisis to a key moment in the credit crunch of 2008. He writes: “This political dance around this financial mess is oddly reminiscent of the days preceding the Lehman Brothers debacle.

“So what will Germany, and France want in return? A strict IMF-style austerity plan. In fact, the IMF could be made to seem like a cuddly teddy bear compared to what’s in store for Greece,” he adds.

On 11 February, an “epic day for the future of Europe”, the EU tells Greece to make further spending cuts. The plans trigger riots in the streets.

May

Eurozone members and the IMF agree a 110bn-euro bailout package to rescue Greece.

November

Greek tragedy turns to Irish stew. The EU and IMF agree to a bailout package to Ireland of 85bn euros. The toughest budget measures in the country’s history soon follow.

Read more: Irish banking crisis - what now for Portugal and Spain?

February 2011

Euro leaders set up the European Stability Mechanism – a permanent rescue funding programme, worth around 500bn euros.

April

Portugal reveals it can no longer tackle its debt problems alone and European finance ministers meet in Budapest to discuss a bailout. British chancellor George Osborne uses Portugal’s crisis to justify UK spending cuts.

May

The eurozone and the IMF approve a 78bn-euro bailout for Portugal. In Spain, thousands of protesters take part in a huge demonstration against mass unemployment. International economist Jan Randolph tells Channel 4 News: “Spain is the biggest weakest link in the eurozone”.

June

Twenty-seven heads of states meet in Brussels for scheduled talks but with the fate of Greece hanging in the balance, it is the only talking point in town.

July

A second Greek bailout package worth 109bn-euro is agreed. Without it, many economists feared that Greece would have defaulted on its debt, sparking a wider crisis which could have engulfed the likes of Ireland and Portugal and ultimately put serious strain on the single currency itself.

More from Channel 4 News: Will a Greece default save the euro?

August

The ECB announces plans to step in and buy up troubled Italian and Spanish bonds to help lower their borrowing costs. But analysts say this is merely a “sticking plaster” because the move was not driven by affirmative action by Europe’s policymakers but a give-the-markets-what-they-want type reaction. G7 leaders insist they are “determined to react in a co-ordinated manner,” in an attempt to reassure investors.

September

Greek Finance Minister Evangelos Venizelos says his country has been made a “scapegoat” for the EU’s incompetence. Meanwhile, Italy’s credit rating is cut by Standard and Poor’s and the IMF slashes growth forecasts and warns of a “dangerious new phase” for European nations.

Finance ministers and central bankers meet in Washington and call for more urgent action. US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner says EU governments must act to prevent a “cascading default” in the eurozone.

October

Share prices increase as a 3tr euro package is proposed to save the single currency from collapse. The proposals are designed to allow Greece to default on its debts in an orderly way without dragging down other countries and commercial banks.

Germany’s Angela Merkel and her French counterpart Nicolas Sarkozy announce plans for a new system in the eurozone to ensure more binding economic cooperation between eurozone nations.

Eurozone leaders agree to pay Greece its latest round of bailout loans to avoid a default.

On 25 October, European leaders convene in Brussels in a bid to finally get the debt crisis under control. They must complete agreements on three financial deals they hope will satisfy markets and restore stability to the single currency. Economist Jonathan Portes, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, tells Channel 4 News: “The right answer is for the ECB to step in and say we are the lender of last resort, and if this is done credibly and clearly, this would go the furthest to dealing with the eurozone crisis.”

Read more: Euro debt deal is 'wrong answer'