Turkey ban: will protest move from tweets to the streets?

The Turkish government’s decision to ban access to Twitter comes as little surprise, writes Niall Finn, a student in Ankara.

While the brutal police attacks on last summer’s Gezi-inspired protests briefly caught the attention of the international media, the crackdown has continued against all new waves political dissent on the streets.

Just as an authoritarian crackdown on protest was countered by activists increasingly taking to social media, the attack on social media will undoubtedly see Turkish activists once again taking to the streets.

After the funeral of 15-year-old Berkin Elvan, who was killed by tear gas, was met by even more tear gas, there is not much that can shock the opponents of the government.

It was only a matter of time before the authoritarian backlash crossed over into the online world. However for many this feels like a deeply personal attack.

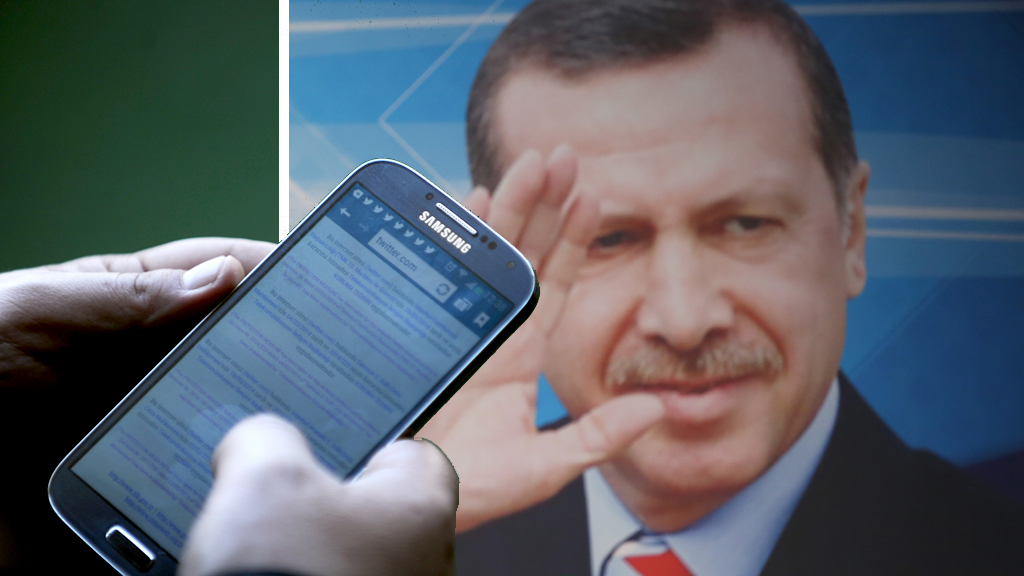

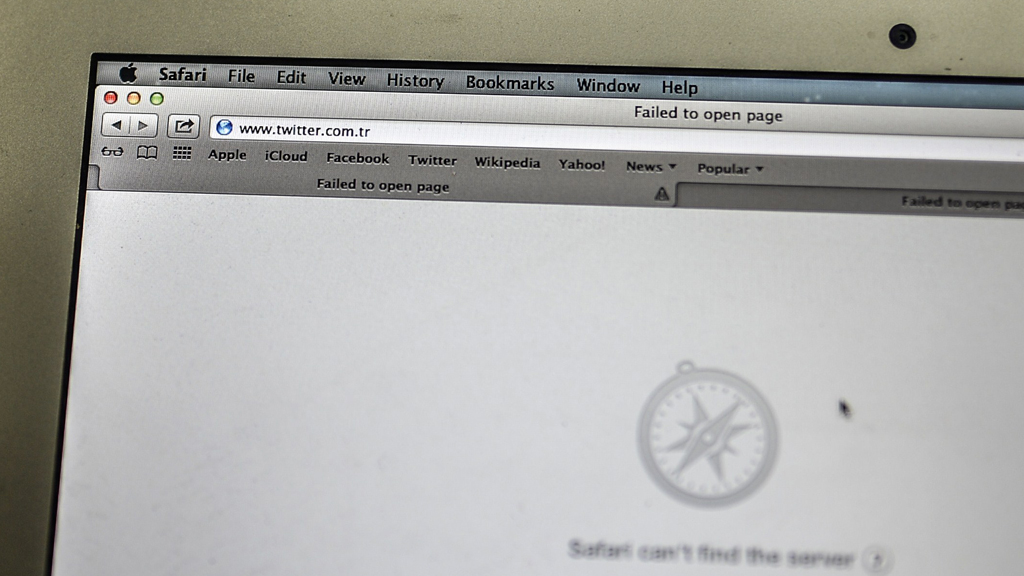

Above: Trying to access Twitter in Turkey

Twitter is a rare space in which individual Turkish citizens are able to collectively voice their criticisms without risk of being beaten or arrested. It is especially potent given Turkey’s dire record on press freedom has left few outlets for alternative news available to the public.

While outraged, many of these tweets ridiculed the government for staring a war they cannot win.

But while the ruling Justice and Development party (AKP) – for the time being at least – still controls the streets and much of the press, they have failed to control social media.

This is not for want of trying. Many AKP politicians have strong Twitter presences, but their attempts to use the medium for their own purposes have consistently met with failure.

Superficial control

Tweets using AKP-sponsored hashtags are almost always ridiculed. On the other hand, rival hashtags have become crucial in organising political dissent. #BerkinSokakta (to the street for Berkin) became a rallying cry to bring people out to protest the 15-year-old’s death.

In a desperate attempt to claw back some territory cyberspace, the AKP has turned to an army of automated “twitter bots” to promote their message.

It was Twitter’s decision to start removing these that may well have sparked the decision to finally ban the site. As undoubtedly did the role Twitter played in spreading the recordings that allegedly implicated Prime Minister Erdogan in a massive corruption scandal.

Read more: Paul Mason on 'Seven reasons why the Turkey Twitter ban matters'

That such recordings were also spread on websites like Facebook and were hosted on YouTube shows the weakness of the government’s position. The AKP can, in reality, only superficially control information spread over the internet.

Many areas (including universities) still retain access to Twitter and contributed to a defiant spike in tweets in Turkey since the measure was announced.

Tweets to streets

While outraged, many of these tweets ridiculed the government for staring a war they cannot win. The political opposition (especially among the young) has long been tech-savy in Turkey, and spawned the influential “Anonymous” style group RedHack.

While a whole generation learnt much from the country’s attempt to ban access to YouTube between March 2007 and October 2010. Across the country people are once again preparing to fire up the proxy servers and VPNs.

While the ban might be by passed and ignored, the symbolism will not. Just as an authoritarian crackdown on protest was countered by activists increasingly taking to social media, the attack on social media will undoubtedly see Turkish activists once again taking to the streets.

Niall Finn is a student at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara. He tweets as @NiallFinn