Black and white students learning together: a dying dream?

1960s campaigns made massive strides in de-segregating US education. But as requirements on schools to educate black and white students are relaxed, re-segregation is becoming increasingly prevalent.

“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever”.

These were the chilling words of George Wallace in his inauguration speech as Governor of Alabama in 1963, writes Anja Popp

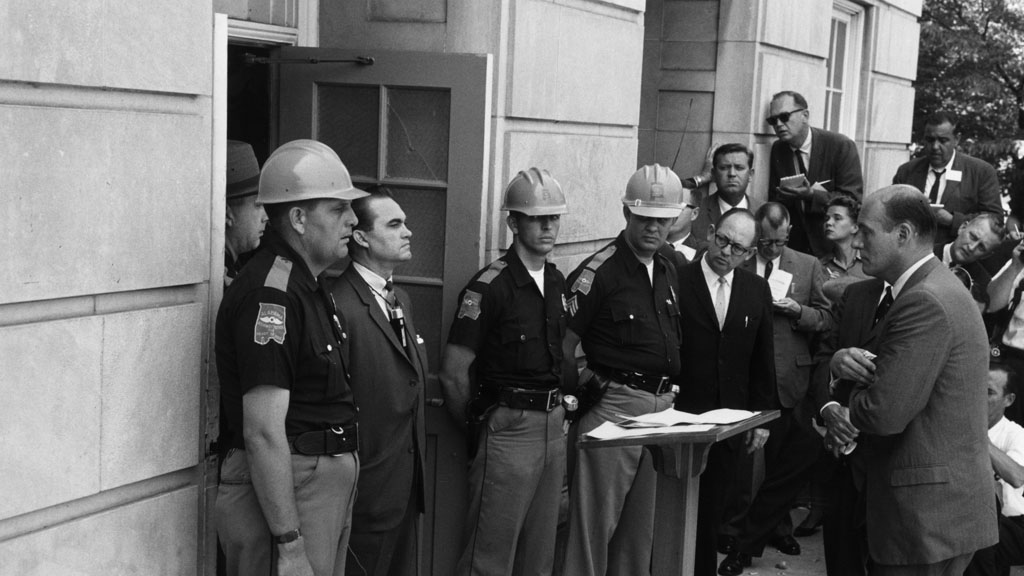

His message was clear: white and black children should not be taught in the same classroom. He later tried to stop two African American students from entering the University of Alabama (pictured above).

Outrage to Wallace’s actions helped fuel the journey to racial equality in education, and the creation of the Civil Rights Movement the following year. After failure in the South to see change after the landmark 1954 court case, Brown v. Board of Education, there seemed to be real movement out of the dark quagmire of racial segregation.

And there was. For a generation, races, classes and schools mixed. Just as Martin Luther King Jr dreamed for Alabama.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- subtitles off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

Let’s fast-forward to now; in the century where a black president sits in the White House and to the outside world, America’s racial woes seem to have dissipated.

However under the surface of this polished picture of an integrated America, runs a fear that the school system is slowly reverting back to what it was.

The lifting of desegregation court orders in the Deep South and beyond has caused people to question – segregation again?

‘Apartheid’ schooling

More and more students are finishing school having never learned alongside the opposite race. Research done over a year by ProPublica shows the number of “apartheid” schools – where the number of white students is one percent or less – has almost tripled nationwide since the peak of integration.

There were 2,762 of these schools in 1988. That figure grew to 6,727 in 2011.

They also found that 53 per cent of black students in districts in the South, released from desegregation orders between 1990 and 2011, currently attend schools where 9 out of 10 students are a racial minority. In 1972 it was only 25 percent.

The reasons for the return aren’t black and white.

Although resegregation is not exclusive to the South, the loss is felt more there, where the battle was fought, and won, for racial integration. During the 70’s and 80’s when racial integration was underway, the achievement gap between black and white 13-year-olds was cut roughly in half nationwide.

Read more from Kylie Morris - Sweet home Alabama: US segregation, 60 years on

Despite this, over-capacity schools and long bus commutes led to the creation of new schools, often built in rich, white neighbourhoods.

Boundary lines were redrawn and some schools have slowly reverted back to the days where you left school not knowing anyone but those of your own race and class.

Journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, who wrote the ProPublica article, describes it as “a story shaped by racial politics and a consuming fear of white flight”. So-called white flight, where white students left the public schools for the private system, led to a gerrymandering of school boundaries to encourage them back into the city.

Once a school was released from a court order, the school board could assign students however it chose, as long as it wasn’t evident that it was done for discriminatory reasons.

Integrated benefits

The system has changed in favour of resegregation. A divided US Supreme Court ruled in 2008 that public school systems could not seek to achieve or maintain integration through measures that explicitly take into account a student’s race.

So what has been lost in the re-emergence of segregated schools?

A University of California at Berkeley study released this year by Rucker Johnson, highlighted the gains of integration.

His study found that black Americans who attended schools that were forced to integrate, were more likely to finish school, go on to university and earn a degree than their counterparts who went to all-black schools. Five years of integrated study also led to them earning 15 per cent more and significantly decreased the likelihood they’d spend time in jail.

The study also found that white students in integrated schools did just as well academically as those in all-white schools, and were more likely to carry on integrating later on in life.

States up and down the US are involved in active cases with the Department of Justice, to change their desegregation requirements. Missisippi leads the way with 44 cases, shortly followed by Alabama. However, schools in New York, Illinois and even California are more racially segregated than those in the Deep South.

New York City has the largest school system in the US, and with that, the greatest integration issues. The Civil Rights Project found less than one per cent white enrolment at 73 percent of charter schools.

A 2011 study by the American Economic Journal claimed that within 10 years of being released from court orders for desegregation, schools unwound 60 per cent of the integration they’d accomplished under the order.

Who knows where they’ll be in another decade.